eBook - ePub

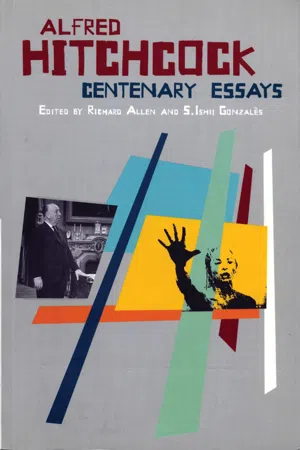

Alfred Hitchcock

Centenary Essays

This is a test

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection of essays displays the range and breadth of Hitchcock scholarship and assesses the significance of his body of work as a bridge between the fin de siecle culture of the 19th century and the 20th century. It engages with Hitchcock's characteristic formal and aesthetic preoccupations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Alfred Hitchcock by Richard Allen, Sam Ishii-Gonzales, Richard Allen, Sam Ishii-Gonzales in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Figure of the Author

The dandyism of sobriety – Alfred Hitchcock

Chapter 1

The Dandy in Hitchcock

Thomas Elsaesser

Not only every generation, but every critic appropriates his or her own 'Alfred Hitchcock', fashioned in the mirror of the pleasures or uncanny moments one derives from his films. Most scholars have arrived at their Hitchcock by paying scrupulous attention to his work, to the individual films, as is quite proper – the more so, since Hitchcock the man was an exceptionally private person. And yet, most are aware of the paradox that this private person also cultivated an exceptionally public persona quite apart, or so it seems, from his work. From very early on in his career he was a star, he knew he was a star, and he dramatised himself as a star.

The question occupying me in this paper is whether in this most self-reflexive of cinematic oeuvres we do not find a 'portrait of the artist'. Not, of course, of the historical individual – that can be left to the biographers – but of the type of creative being, bridging and maybe even reconciling the rift that in the past, before he became a classic, so often appeared in Hitchcock criticism: between the entertainer and the 'serious artist'. Rather than take the usual route of polarising the two terms, I want to make my tentative answer hinge upon what I consider to be the enigma of Hitchcock's Englishness.

In the critical literature, there is no shortage of coherent images of Hitchcock. No need for me to present them in detail: the Catholic and Jansenist, the artist of the occult forces of light and darkness, the master-technician, the supreme showman, and so on. In Britain, two Hitchcocks dominated the crucial period of revaluation in the 1960s. One, found in the pages of Sight and Sound, was characterised by either disdainful or regretful dismissal of the American Hitchcock. The foil for it was a preference, nostalgically tinged, for the craftsman-stylist with an eye for typically English realism or social satire. Polemically opposed to this view was Robin Wood's Hitchcock, who emerged not only as a very serious artist, but one who in his American films had a consistent theme, almost a humanist concern: the therapeutic formation of the couple and the family.1 Such a notion of Hitchcock the moralist was already anticipated and rejected by Lindsay Anderson when he wrote in 1949: 'Hitchcock has never been a serious director. His films are interesting neither for their ideas nor for their characters. None of his early melodramas can be said to carry a message, and when one does appear, as in Foreign Correspondent, it is banal in the extreme . . . In the same way, Hitchcock's characterisation has never achieved – or aimed at – anything more than surface verisimilitude.'2

Peter Wollen might be said to have developed his Hitchcock in opposition to both of these English constructs, apparently leaning more towards seeing him as a director who subverts the morality, the politics and the realism of his sources, in order to exhibit their narrative and structural mechanisms. 'For Hitchcock it is not the problem of loyalty or allegiance which is uppermost, but the mechanisms of spying and pursuit in themselves.'3 But these mechanisms, as Wollen wisely adds, 'have their own psychological significance. In the end we discover that to be a master-technician in the cinema is to speak a rhetoric which is none other than the rhetoric of the unconscious.'4 Since then, almost all the major readings of Hitchcock have followed and explored this path, often with spectacular success. The very force and cogency of this success – notably through Raymond Bellour's work, strongly persuading us to accept a definition of the American cinema and of classical narrative remade in the image of Hitchcock – makes me, perversely, want to look for a more limited, historical, more English and more 'ideological' Hitchcock.

I take my cue from a few casual remarks by Raymond Durgnat, who has commented on Hitchcock's affinities with Symbolism and Decadence. Durgnat writes: 'Since the cinema is traditionally associated with the lower social grades, a man who delights in perfectly wrought film form is likely to find himself referred to as a master craftsman, and the full sense of his involvement with aesthetics is missed . . . Hitchcock is as lordly as any Symbolist of l'art pour I' art . . . A craftsman whose craft is aesthetics and who takes a deep pleasure in practising it as meticulously as Hitchcock does, is an aesthete.' And Durgnat points to a spiritual affinity with Oscar Wilde, calling Hitchcock 'an epicure of suspense and terror' whose films bring to mind 'titles of the Decadence: Le Jardin des Supplices, Les Fleurs du Mal'.5 It is this cultural sensibility and aesthetic temperament that I want to investigate a little further.

Is Hitchcock an aesthete in his work, and as Durgnat implies, was he a dandy in life? Let me remind you of some typical attitudes that are supposed to make a dandy. A dandy is preoccupied, above all, with style. A dandy makes a cult of clothes and manners. A dandy has an infinite capacity to astound and surprise. A dandy is given to a form of wit which seems to his contemporaries mere cynicism. A dandy must be negative: neither believing in the world of men – virility, sports – nor in the world of women – the earthy, the life-giving, the intuitive, the natural and flowing. A dandy prefers fantasy and beauty over maturity and responsibility, he pursues perfection to the point of perversity. He is, to quote an authoritative study, 'a man dedicated solely to his own perfection through a ritual of taste . . . free of all human commitments that conflict with taste: passion, moralities, ambitions, politics or occupations'.6 And he despises everything that is vulgar, common, associated with commerce and a mass public.

Now, granted, it is difficult to recognise in this description the familiar and portly figure, dressed in sober business suits; Catholic, devoted husband and father, the son of a grocer; the quiet, private upholder of domestic virtues par excellence. It is difficult if not incongruous to discern in the familiar silhouette the traits of a Baudelaire, or Oscar Wilde, or Proust or Diaghilev. Neither does there seem to be any connection, either directly or indirectly, with the British Pre-Raphaelites or the Bloomsbury Group. None of the gregariousness, none of the in-group rituals, but also little of the élitism or the anti-democratic exclusivity of the European aesthetic coteries in literature or the performing arts.

But let us look a little further: sartorial dandyism, the cult of clothes. True, Hitchcock wore sober business suits, but he always wore them, in every climate, in his office, on the set, in the Californian summer, in the Swiss Alps or in Marrakesh. As John Russell Taylor remarks: 'When he was filming he would turn up punctiliously at the Studio every day disguised as an English businessman in the invariable dark suit, white shirt and restrained dark tie. In the 1930s the fact of wearing a suit and tie, even in the suffocating heat of a Los Angeles summer, was not so bizarre as it has since become, but in a world where many of the film-makers affected fancy-dress –De Mille's riding breeches, Sternberg's tropical tea-planter outfit – Hitch's was the fanciest of them all by being the least suitable and probable.'7 Quite plainly, Hitchcock was applying a most rigorous public gesture: the dandyism of sobriety.

The ritual of manners. It already annoyed Lindsay Anderson that Hitchcock, when he came to London, stayed at a luxury hotel. It smacked to him of Bel Air snobbery, contempt, and a vulgar display of money. The point, however, was that Hitchcock always stayed at the same hotel, in the same suite at Claridges, just as at home, he always had dinner at Chasen's. Affecting a superstitious nature, a fear of crossing the street or driving a car was part of the same public gesture: to make out of the contingencies of existence an absolute and demanding ritual, and thereby to exercise perfect and total control, almost as if to make life his own creation. It is a choice, not so different from, say, Ronald Firbank's, a notable dandy of the 1920s who, after moving to another part of London, decided to retain his gardener, but insisted that the gardener should walk, in a green baize apron and carrying a watering can, from his lodgings along Piccadilly and Regent Street to Firbank's new home in Chelsea.

Hitchcock's daily rituals, which he made known to everyone, are not only a rich man's indulgence of his own convenience, they touch one of the dandy's main philosophical tenets: to make no concessions to nature, at whatever price. Hitchcock's life, which has been seen as that of 'a straightforward middle-class Englishman who happens to be an artistic genius',8 seems in its particular accentuation, its imperviousness to both change and time, more problematic, more enigmatic than merely the attempt to cling to the values of his native country, out of season, as it were. Nor is it simply the mask of a man whose painful shyness makes him adopt a role that everyone recognises and therefore dismisses: for that, his work is too much obsessed with domination – of who controls whom by the power of the gaze, of fascination and its objects. More pertinent, then, is the suggestion that Hitchcock's lifestyle was a determined protest, the triumph of artifice over accident, a kind of daily victory over chance, in the name of a spirituality dedicating itself to making life imitate art. The revolt against nature, of course, is one of the strongest traditions of European aestheticism and dandyism – from Baudelaire's Paradis Artificiels, via Huysman's À Rebours, to Oscar Wilde's The Truth of Masks and The Decay of Lying. From the latter comes the most well-known defence of Hitchcock's use of back projection, process shots and studio sets: 'The more we study art, the less we care for nature. What art really reveals to us is nature's lack of design, her curious crudities, her extraordinary monotony, her absolutely unfinished condition. Nature has good intentions, of course, but as Aristotle once said, she cannot carry them out. When I look at a landscape I cannot help seeing all its defects. It is fortunate for us, however, that nature is so imperfect, as otherwise we should have no art at all. Art is our spirited protest, our gallant attempt to teach nature her proper place.'9 Hitchcock fully responded to Wilde's challenge when, famously, he said: 'My films are not slices of life. They're slices of cake.'10

As in his work, so in his life Hitchcock excelled in turning a cliché inside out. Everyone is agreed that he was a professional, an addict to work. Yet, part of the image of a dandy is that he disdains work. Hitchcock was able to cultivate both images simultaneously: that of perfection and of effortless ease. A film is finished before it is begun: creation takes place elsewhere, in another scene, not in the process of filming. No commentator leaves out the description of Hitchcock on the set, sitting in his director's chair, appearing languid, his mind on something else, or simply looking bored. He made a point of never looking through the camera lens. 'It would be as though I distrusted the cameraman and he was a liar . . . I don't rush the same evening to see "Has it come out?" That would be like going to the local camera shop to see the snaps and make sure that nobody had moved.'11

This immobility is another important clue: the true work of the dandy is to expend all his effort on creating about his person the impression of utter stasis. One recalls the sphinx-like profile he presented as his trademark, and in later life, his public appearance was designed to accentuate the statuesqueness of his massive body. Disarmingly, he turned himself into his own monument, aware of his own immortality. Of course, he carried it lightly, like the wax effigy with which he let himself be photographed and which, deep-frozen, appeared among his wife's groceries in the refrigerator. In a typical inversion of a romantic motif – that of the double – Hitchcock rehearsed his own death and lent it the semblance of life.

If his working methods show a disdain for improvisation, his films stand and fall by the degree to which they exhibit the intricacies of their design. While one can interpret this as a need for order, for control (and the domination of recalcitrant material is clearly part of the film-maker's ambition to possess the world and fix it through the gaze), it is equally the case that in the quality and patterning of the scripts, Hitchcock manifested a most ex...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- List of Contributors

- PART I: THE FIGURE OF THE AUTHOR

- PART II: HITCHCOCK'S AESTHETICS

- PART III: SEXUALITY/ROMANCE

- PART IV: CULTURE, POLITICS, IDEOLOGY

- Bibliography

- Index

- eCopyright