This is a test

- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

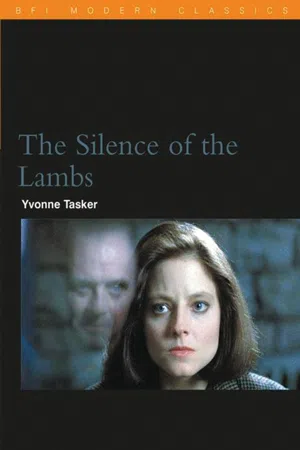

The Silence of the Lambs

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this study Yvonne Tasker explores the way the film weaves together gothic, horror and thriller conventions to generate both a distinctive variation on the cinematic portrayal of insanity and crime, and a fascinating intervention in the sexual politics of genre.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Silence of the Lambs by Yvonne Tasker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Birds, Lambs and Butterflies

Oscar night 1992: host Billy Crystal is wheeled on stage in a Hannibal Lecter-style hockey-mask. The Silence of the Lambs goes on to become one of only a few films in recent years to take the ‘top’ five awards: Best Director for Jonathan Demme, Best Actress for Jodie Foster, Best Actor for Anthony Hopkins, Best Picture for producers Ron Bozman, Edward Saxon and Kenneth Utt, and Best Adapted Screenplay for Ted Tally. Reviewed as a ‘chilling psychological thriller’ and hyped as the scariest film of the year, Silence was only the second R-rated movie to achieve such a sweep, although R-rated films have regularly been awarded Best Picture since the US introduced a ratings system in the 1960s.

The Silence of the Lambs centres on the search for a serial killer, known only as ‘Buffalo Bill’, who abducts young women seemingly at random: all his victims are white and all are large. Bill imprisons these women in a dry well sunk in the heart of his labyrinthine basement, starving them for three days before shooting and skinning them. Their mutilated corpses are then dumped in rivers across the United States. Finally surfacing in random fashion, Buffalo Bill’s victims feed the investigations of an FBI team led by Jack Crawford that has, despite the appearance of five bodies, had little success in tracking the killer. The FBI find themselves literally clueless: the water eliminates trace evidence and no single factor seems to link all the victims to each other or to their killer. Meanwhile, in the privacy of his basement, Buffalo Bill is carefully and skilfully constructing a garment out of the flayed flesh of his victims.

Though Buffalo Bill has been at his work for some time, The Silence of the Lambs is tightly structured around the intensive investigation that is triggered by the abduction of Catherine Martin, the daughter of Republican Senator Ruth Martin. Lured into a van –Bill gains her trust by wearing a cast on his arm in the fashion of serial killer Ted Bundy –Catherine is introduced and then abducted about thirty minutes into the movie. From this moment on, both audience and investigators know that they are involved in a race against time. The search for Catherine drives the narrative forward, while the dialogue features repeated references to the passing of time.

The film’s premise would already have been familiar to readers of Thomas Harris’s best-selling 1998 novel, and in rather more gruesome detail. The novel provides us with details of, for instance, the particular way that bodies decay in water, how they can be scorched in the trunk of a car after death, or the ‘fiendishly difficult’1 aspects of managing human skin, all details that the film sets to one side. Despite his meticulous research – working with the FBI, examining the cases of actual serial killers and so on – Harris is probably best known for creating the rather fantastic character of Hannibal ‘The Cannibal’ Lecter. In turn, this unlikely role made the well-respected Welsh actor Anthony Hopkins into a fully-fledged film star. A former psychiatrist who killed and ate his victims, Lecter is the film’s evil genius, a seductive variety of mad scientist. More importantly in terms of the quest for the killer and for Catherine, Lecter knows the identity of Buffalo Bill.

The FBI, Buffalo Bill and Catherine herself all structure their activities around a three-day cycle at the end of which Catherine will either die or be saved: either the killer or the FBI will have their trophy. While Lecter could reveal what he knows at any time, he has none of the investigators’ urgency: ‘All good things to those who wait,’ he lectures FBI trainee Clarice Starling, and later, as Catherine’s time is running out: ‘We don’t reckon time the same way.’ In the scene that immediately precedes Catherine’s abduction Lecter demonstrates his knowledge of the killer while hinting at the different sense of time by which he operates: ‘I’vewaited, Clarice. But how long can you and old Jackie boy wait? Our little Billy must already be searching for that next special lady.’ Lecter’s knowledge allows him to threaten by proxy. Thus, while The Silence of the Lambs is in one sense led by the urgent pace of pursuit, it simultaneously follows a different sort of narrative logic, or at least a different narrative time, one organised around – and even dictated by – the charismatic Lecter.

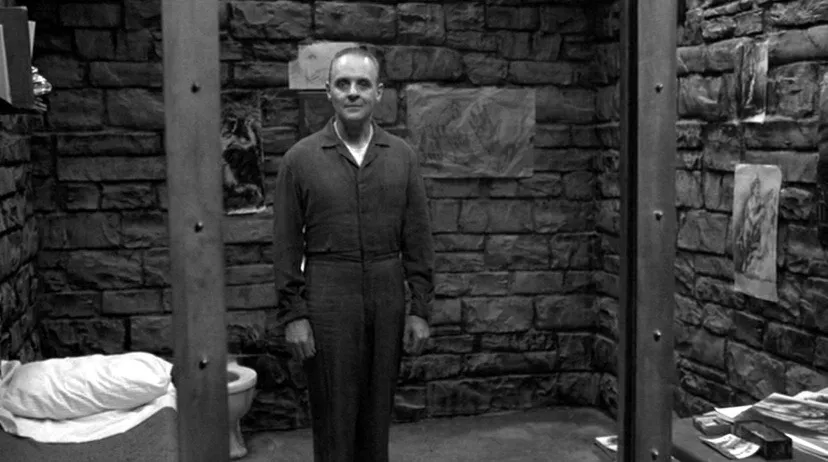

Lecter’s sense of time is palpably different; both his speech and his movements are careful and measured. Hopkins invests the Doctor with grace as well as malice, both conveyed through small but nonetheless powerful gestures (self-possession evident in the slow closing of the eyes, decisiveness in the movement of a hand, for instance). Lecter spends the majority of the movie imprisoned, his cell a scene to which we repeatedly return. The sense that Lecter is a knowing character is not limited by his restraints or his surroundings – he reaches out from his cell, manipulating others through words and the lure of their own desires. Verbally he is at his most brutal when bound and masked. He induces another inmate to swallow his own tongue with the power of his words – precisely what words might have this power we can only imagine since the act takes place off-screen.

Hannibal Lecter, an observer on display

Catherine Martin held prisoner

Central to the film’s construction in both narrative and thematic terms are four lengthy exchanges between Lecter and psychology graduate-cum-FBI trainee Clarice Starling. Jack Crawford, head of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, initiates the first of these meetings, sending Starling to interview Lecter. Her official task is to persuade the killer to complete the Unit’s standard questionnaire for the Violent Crime and Apprehension Program (VICAP). Crawford’s actual agenda – one he does not trust Starling with as yet – is to engage Lecter with the Buffalo Bill case. Lecter and Starling form an edgy but intense bond. Their exchanges are characterised by the tight facial close-ups that Jonathan Demme and director of photography Tak Fujimoto use throughout, often explicitly aligning us with Starling’s point of view. Like Hopkins’s performance, these sequences, although they certainly have their chilling moments, are typically still and controlled, something of a contrast to the more frenetic editing we might expect to find in either the thriller or the horror film. Though The Silence of the Lambs features some spectacular editing, in these meetings at least it is the use of the close-up that is most visually striking, Lecter and Starling talking intimately through the glass that divides them.

At their first meeting Lecter taunts Starling, almost immediately pinpointing her weakness – an anxiety about appearing common – and playing on it: ‘You’re not more than one generation from poor white trash, are you, Agent Starling?’ Although he dismisses Starling himself, Lecter is disconcerted when another inmate, Miggs, splatters her with semen. Perhaps this excites him, or perhaps he seeks to make amends: either way, telling her that ‘discourtesy is unspeakably ugly’ to him, Lecter provides Starling with the first of several clues that will involve her ever more closely in the search for Buffalo Bill: ‘Look deep within yourself, Clarice Starling,’ he tells her. ‘Go and seek out Miss Mofet, an old patient of mine.’ Following a hunch, Starling visits the ‘Your Self ’ storage facility in Baltimore. Here she explores the contents of a unit rented in the name of Miss Hester Mofet, finding the head of one Benjamin Raspeil (in the process decoding Lecter’s anagram: Miss Hester Mofet/miss the rest of me). Raspeil’s head is preserved in a specimen jar, an ironic evocation of the laboratories that are so frequently at the centre of crime fictions. This is a laboratory of a rather different kind: inside an old car, the jar is artfully positioned beside a headless mannequin posed with a woman’s evening dress and cigarette holder. Though the contents of the car have been undisturbed for years, the sense of purpose that underpins this uncanny scene is as intense as its theatricality.

The key to advancement: Benjamin Raspeil’s preserved head

Returning to the asylum for their second encounter, Starling realises not only that Lecter knows the identity of Raspeil’s killer but that she has uncovered another of Buffalo Bill’s victims, perhaps even his first. Less formal now and less intimidated perhaps, Starling sits cross-legged on the floor, her hair still wet from the rain. She addresses Lecter directly and frankly. By contrast Lecter remains a mystery, sat at the back of his cell in the darkness. In seductive tones, Lecter makes an offer of assistance in the case and, implicitly, in fulfilling her desires: ‘I’ll help you catch him, Clarice.’ With his riddles, jokes and imperturbable manner, Lecter seems Sphinx-like – his clues are cryptic, the information he provides only ever partial. Yet in pursuit of her quest, Starling must solve the puzzles that Lecter poses.

When a sixth body comes to the surface in West Virginia, Starling is included in the investigation, going with Crawford to examine the body. She spots something in the victim’s throat: a bug cocoon. Entomologists at the Smithsonian – first discovered in the darkness playing a bizarre sort of insect chess – identify the pupal stage of the death’s head moth. The FBI subsequently discover another such cocoon preserved in Raspeil’s head. Here at last, above and beyond the abduction, murder and skinning of women, is the killer’s signature. Buffalo Bill wants to transform himself somehow; rejected for gender reassignment he now looks to become not a woman as such, but a sort of human butterfly. Transformation is one of Silence’s central themes, and it is typically figured in insect or animal terms: the moth and the bird. The moth or butterfly passes through stages, literally shedding skin to emerge in its new form. The young bird, once dependent, flies the nest when it is fledged, its feathers newly fit for flight.

The imagery of birds, development and flight is most obviously deployed in relation to Starling herself: in the opening sequence, while running in the woods she disturbs a bird which flies off nosily; on their first meeting Lecter tells her to ‘fly back to school’. A stuffed owl, wings spread, is the first object found by Starling’s torch in the Baltimore storage facility – a little echo of Psycho perhaps (the stuffed birds in Norman Bates’s back room). The tracking point-of-view shot keeps us with Starling; the stuffed and mounted bird is both a threatening object – a little sign of the uncanny – and a warning of one potential fate, summarised in the contradictory spectacle of a frozen image of movement (though Buffalo Bill wears his victims and Lecter consumes his, both stage bodily transgressions by which they incorporate others). Through the course of the film, we witness Starling pass from trainee to Special Agent (we even glimpse her childhood in two brief flashbacks), a narrative of growth and maturity. Fredericka Bimmel, Buffalo Bill’s first victim, is also associated with birds. Photos on her bedroom wall show happy scenes with her father at the pigeon coop, the background embellished with childish drawings of birds and branches. Lecter also describes Buffalo Bill through the analogy of the bird, casting Raspeil’s murder as ‘a fledgeling killer’s first effort at transformation’. Beyond her name, Catherine Martin has little of the bird about her, although this much links her to Starling.

Transformation: investigators discover a moth in the West Virginia victim’s throat

Other than the obvious – he escapes capture – transformation is not at issue with Hannibal Lecter. He remains seemingly fixed throughout. If any animalistic metaphor were to suggest itself, it would be reptilian (though in Harris’s novel he strikes Starling as a ‘cemetery mink’ who ‘lives down in a ribcage in the dry leaves of a heart’2). Lecter typically mocks and even exploits the labels that are assigned to him (whether to induce fear or to lull others into a false sense of security). In their third interview, Starling attempts to take the upper hand. Brushing aside the self-important asylum director Dr Frederick Chilton, she puts a false offer to Lecter in Senator Martin’s name (thus explicitly usurping a powerful woman’s authority). In return for his help, Lecter will be transferred to another institution. Starling masks the FBI’s false offer with a perverse detail given the film’s use of animal imagery – the island where he will have a week’s freedom each year is an animal disease research centre. Lecter agrees to help but only in return for personal information from Starling: she promises Lecter a beach with nesting terns, but he quickly insists on turns of a different kind: ‘I tell you things. You tell me...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Birds, Lambs and Butterflies

- 2. The Sum and the Parts: Horror, Crime and the Woman’s Picture

- 3. Detection and Deduction

- 4. The Female Gothic

- 5. Under the Skin

- Notes

- Credits

- eCopyright