- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

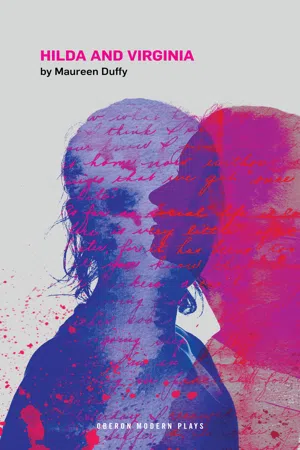

Hilda and Virginia

About this book

Maureen Duffy's double-bill tells the story of two remarkable women. The Choice is the story of a very unsaintly saint. Hilda of Whitby, who brought Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons, was a businesswoman, teacher and adviser to kings. In A Nightingale in Bloomsbury Square, Virginia Woolf looks back on her life, uncovering the hidden stories behind her iconic novels. From the torture of depression to the scandal of her lesbian affairs, Virginia goes down fighting. As the saying goes: well-behaved women don't make history…

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

VIRGINIA

There’s nothing more to be done. I have written to my husband and my sister that I’m mad and can’t go on.

You’re all the same. You want to slice the top off my head as one does with an egg; get the spoon down into the yolk; prod about until you come up with something dripping yellow, a black bloody speck that might have grown into a winged thing, shaken out pinions, and taken off; then clap the top of my head back on over emptiness and say, ‘There you are, cured.’ But I’m not mad. I never was, have never been and now I never will be.

One writes so to them because that’s what they believe, want to believe. It makes it easier for them. The mad aren’t responsible, by definition, so their acts and words can’t hurt. They don’t mean what they say and one has no responsibility to understand them. Make the mad rest, lie still, suck up nourishment, be vegetable and gradually they will stop talking. Turnips don’t talk. Only the apples talk when Leonard sorts them while I’m writing, soldiers them into files like a greengrocer’s parade ground, fit, bruised, rotten. But the beet out there, squelched down in their mud beds are as quiet as planted dead. That’s your rest cure. Even Freud never believed in it.

What was it he wrote:

‘If a neurasthenic woman suffering from anxiety is taken away from home and sent to a hydrotherapeutic establishment…one is naturally inclined to give the credit for the splendid improvement which often sets in within a few weeks to the quiet life which the patient has been enjoying…

Soon after the patient has returned to her ordinary way of life, the symptoms of the trouble reappear and force her from time to time to spend a part of her existence unproductively in establishments of this kind, or else to turn in another direction for hope of recovery.’

We published that in 1924, when I was writing Mrs Dalloway. Shall I tell you what I wrote then; what I made Clarissa say about Septimus and the neurologist? ‘Suppose he had gone to Sir William Bradshaw, a great doctor, yet to her obscurely evil, without sex or lust, extremely polite to women – if this young man had gone to him, and Sir William had impressed him, might he not then have said, Life is made intolerable; they make life intolerable, men like that?’

Freud and I quoted against each other like two nightingales singing out our territory in the darkened wood. If I sing loudly enough and as long as I keep on singing you can’t cross my borders. You mustn’t come into my thicket. And I wouldn’t go into his.

I hate ‘the possessiveness and love of domination in men.’

Now did I say that? No, Vita remarked it of me to her journal but it’s true. I’ve said it myself, of and to myself and to my writing often enough. And besides there were those two physicians who presided over the first years of my marriage with names that should have warned anyone away from their brass plates: Savage and Head. They have a term these days the young, an American import I suspect, head-shrinker. They wanted to shrink my head or savage it, those two charlatans.

Why did Freud give me a Narcissus when Leonard and I went to see him at Hampstead when he was dying? In the hope of Spring perhaps. He talked of Hitler and wondered what the British would do about him. He was old and ill, a Jewish refugee and he frightened me for Leonard. Freud had run to England. But where could we run if Hitler should come here stamping a yellow star on my husband’s forehead with his black jackboot. Freud escaped, of course, by dying, although he can hardly be blamed for that.

No one is ever truthful. Everyone shifts, makes shift, is shifty and shiftless, is a chameleon and a shape-changer. Most of all they use words to fog or blind. Freud walked in like an old magician in a dusty, ragged cloak with the stars gone out and only holes to show where they were and offered transformation but I know about words. I know how to hide behind them as well as anyone. And I’m still hiding in those two letters I have spent the morning writing. Most of all in those.

Because the truth is…insupportable.

Everyone’s is I suppose, but mine more than most. Others manage; they go on. Leonard will go on and Vanessa and Vita. The people I love will go on and on and on. Yet a little while ago Leonard and I were busy with plans for a suicide pact.

That phrase makes it sound so vulgar; a cheap banner headline. “Couple in death pact”. But it was a rational and necessary precaution. Otherwise Adrian, my brother wouldn’t have procured us a lethal dose. They say very little morphia will do the trick. Except where the patient has a high tolerance of drugs. After a lifetime of veronal and digitalis my brain must be a combination of herbalist and alchemist.

An autopsy would find my heart blooming like a foxglove and my liver shaped to a retort. Perhaps Adrian’s dose wouldn’t have been enough. Enough for Leonard; and I should have had to go back to our first plan: the engine running in a confined space, the gas drawing down charcoal clouds over the eyes.

Yet I have to admit it. Last summer Leonard and I lay under the trees while the bombs fell. The aeroplanes hummed and sawed and buzzed over us and the guns at Ringmer answered with August thunder and we expected, flatly, to die; after that day there was no more talk of suicide. Anyway Leonard never believed in it. And now it’s no longer necessary. Unbelievably the English have survived.

We can’t be sure Hitler’s forgotten us. At any moment he could turn and be at our throats again. He is still powerful and unbeaten, even if soon he will be treading in the footprints of Napoleon to waste himself in the snow. But that isn’t why it has come back to me alone, now that the fear of invasion draws away.

I won’t look.

Freud died in peace after a third grain of morphia. Why shouldn’t I? When they brought his dog to him in the last days it was afraid.

It howled and cringed in the corner. The smell from the wound. That would be to be truly alone if one’s dog should cringe away like that. Freud would say I am less than two thirds his age, I have work to do, books to write, people who love me.

Failure, all failure. He had children. I had only those dream children, my books. Freud had books and children.

My sister Vanessa had children and her painting even though I despised her painting and called it a low art.

I was so happy when Violet Dickinson sent me a cradle when we came back from our honeymoon: fit for the illegitimate son of an Empress. ‘My baby shall sleep in it,’ I said. And then they decided that there would never be any babies. Even Vita had two boys. Freud had Anna, Ernst and Oliver, Martin and Mathilde…

Would I have liked Leonard to be a Jewish patriarch? Would he have had the time to care for me to note every fluctuation in my health?

Those notes: V.n.w., Virginia not well; b.n., bad nigh; V.sl.h., Virginia slight headache. A calendar of my sins like those other records of every penny spent. The household books my father totted up my mother’s days in. We would end in the workhouse my father said, among the ignoble poor. Are all men the same, endlessly addi...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hilda and Virginia by Maureen Duffy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & British Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.