![]()

Creating movement

On a first day in the studio I’m so loaded up with information most of the time I have no idea what I’m going to start with, right up until after class. It depends how I feel. There are so many possibilities and already all the dancers around me and all the things I can do with them is messing with my head. Sometimes I just go ahead and make the piece in my mind, start at the beginning and work through. But these days I tend to begin with just movement, not in any set order, just finding a language, a vocabulary. And this is the process I’m going to write about.

The first port of call, and the most allusive thing to tap, in the studio, is simply whether you are in the state of being of the animal that is going to create good movement. Attaining this is always unpredictable and inconsistent, you have good days, OK days, and bad days, though through experience you get better at finding it within yourself – what to shut off, what stimulates you.

Here are two contradictory things I do simultaneously: I don’t ‘think’ when I first initiate movement. I tap into the feeling of what I am going to express. I earn this indulgence through my preparation. That work is inside me. Now I can move from the heart – cross over to the primal power of movement that transcends cold conscious thought. Now the contradiction – I do need to think. Let’s go back to my introduction to choreography – Muhammad Ali; when he was in the ring he wasn’t just the fighting animal; he’d use his mind at the same time, making decisions, analysing ways to outsmart his opponent; he would utilise his craft alongside all kinds of tricks – physical, mind games – watch the film When We Were Kings. The trick is to have the mind and body working in tandem.

PHRASING

So I make some phrases. Often without music. And often, at first, slowly. Every detail of a phrase must be explored; every accent and articulation. A phrase must have a ‘musicality’ of its own, a rhythm and a melody, even if the rhythm is subliminal. It must make sense like a sentence, and any clutter should be removed from it. No element can be vague and it must have subtlety. I will identify the attributes of the overall physical identity of a phrase – something is going on, a feeling in how I’m dancing it, for instance – I’m being hooked by something and dragged and at the end of each move I’m retracting back… The hook feels sharp, bubbles streaming out behind me as I get dragged and the resistance I give makes me feel like I’m underwater. When I’m released I retract through my bones and the next move of the phrase comes from this, and I’m allowing myself a moment of no control over the next move I make, almost falling into it, and this sets up the next ‘line’ I hit. This is the animal talking, while my mind will work out what I am doing technically with my body. I identify where each movement is coming from – the impulse – and become more specific about the accent, find out what its potential is. Often I will find that the impulse isn’t even coming from me – it is like something external is hitting me, pushing me, I am receiving something other. Where does movement really start? Never forget you are touching those invisible powers, spirits, ghosts, ancestry deep inside you, and from the world outside. The same place those ideas come from. When a movement really takes me at first I have no idea where it comes from. It hits me before I can think. But all this has to be eventually broken down technically so you can communicate this information to your dancers.

LINE

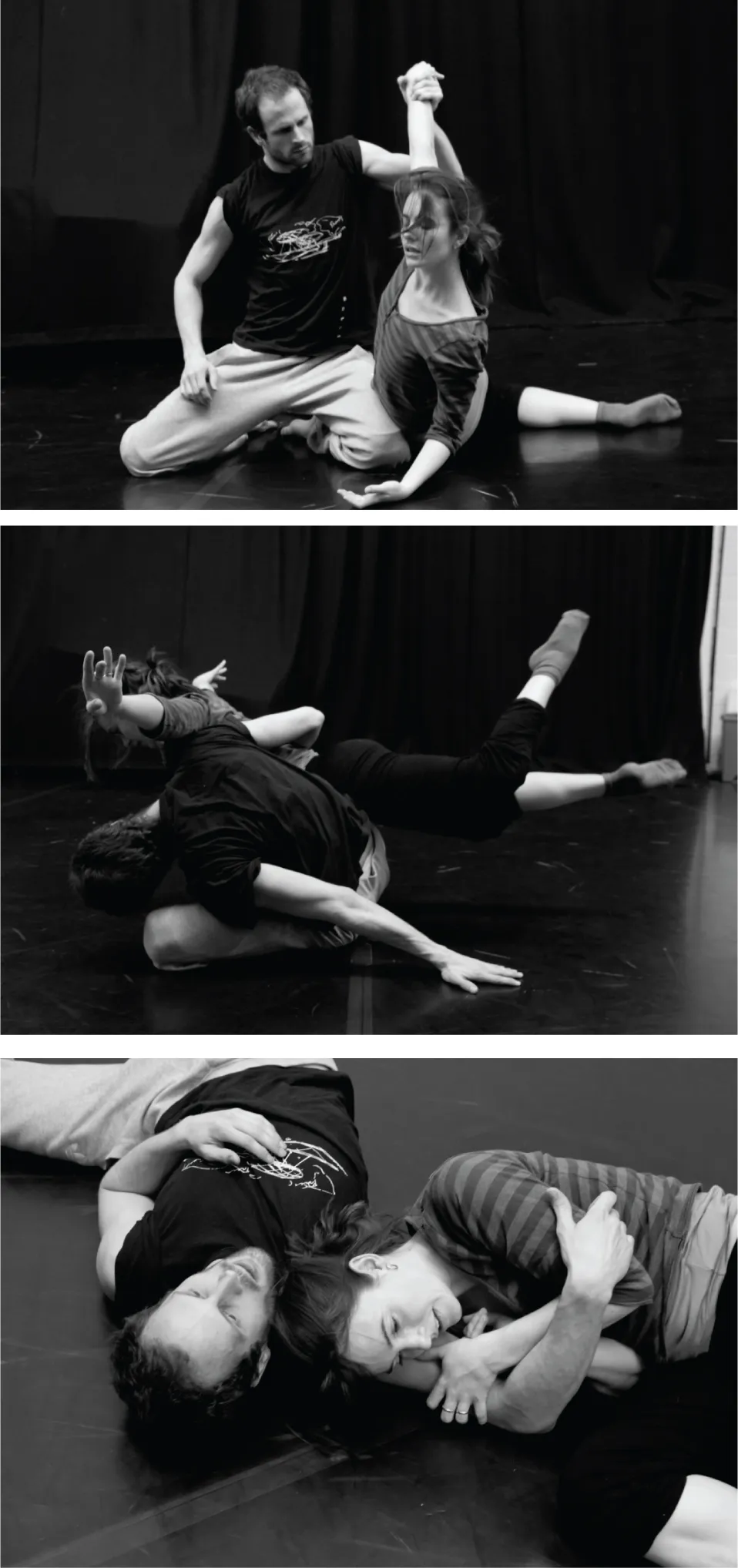

Line is an essential part of the identity of a phrase. Line or ‘picture’. When you are dancing you are constantly creating pictures in the viewer’s mind. Sometimes these are obvious, sometimes they are almost subliminal. Things they will remember. These pictures will tell them something – abstract or literal. Let’s look at some pictures. My phrases will be peppered with these pictures/lines – what do they say?

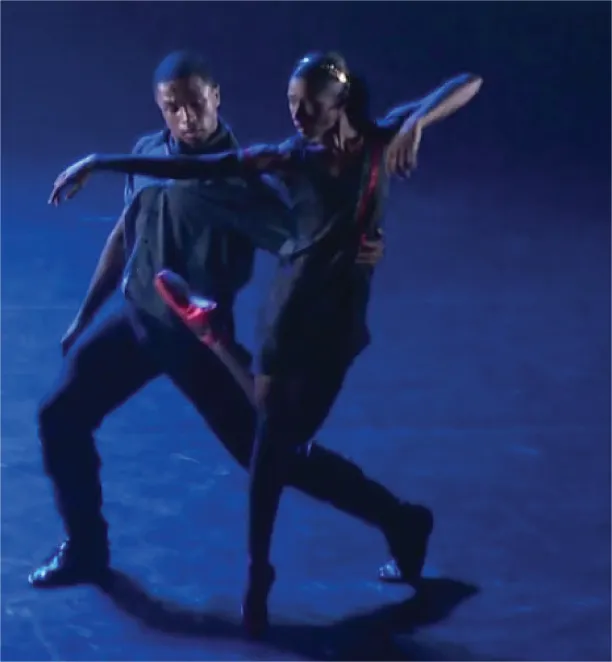

Or very different – using much more traditional lines:

All your decisions will log inside the viewer and will form the basis of what they are experiencing. You are guiding them, manipulating them. Line means anything – from a traditional dance position to something as small as the tension in someone’s fingers; where someone is looking (look at the last image above – how different would it be if both dancers were looking out towards the audience?). Small details can completely change a viewer’s perception. Often when revisiting a phrase and finding that it it isn’t working like it did can be because some of the ‘pictures’ are a little out of focus. We can see this immediately in ballet – if someone doesn’t hit that arabesque the moment is lost. This works in the same way with every picture you create. A simple exercise – do a phrase with you eyes looking down, then with your focus out. It changes what the phrase communicates. Even simpler – hold out your hand with your palm open, look into your hand, look away from your hand, look towards the audience, does this suggest giving? Does it suggest it more if you look towards the audience, or does it become begging? Open your other palm, so two hands now, a subliminal image of Jesus Christ? What if you are on your knees. Now do all this with clenched fists. What does that say? Any line you are hitting – what is it? Can you make it clearer, better? Do you want to alter it, maybe extend it?

DEVELOPING MOVEMENT VOCABULARY

Having been through the process above and narrowed down the elements of a vocabulary I am exploring, I will limit myself to these ingredients and make some more phrases in the same style. Then I’ll break these phrases down again, push some of the attributes and all the time work on technically isolating the impulses of the physical identity, the accents and details so I can get rid of any physical clutter around them. This is the same process you go through as a dancer – only using what one has to in order to execute a phrase. I am refining all the time; even if the phrase is like a rag doll being dragged around by its hair – you want it to be only that – no mud in it. Although that’s quite a nice idea – a rag doll and some mud. I sometimes do this – add a wildcard into the phrase, see what that does to its identity.

By releasing the parts of the body I don’t need to execute a movement I can either do nothing or possibly something else with them. I will also try using the same impulse from different sources in the body. I will challenge, change the direction of a phrase, stop the flow through a movement and take it somewhere else, change the attack, where the commas are, or hit one accent a little harder than before – anything that makes it less predictable. A viewer will ‘see’ all this work, even though they won’t see it. I will experiment with the speed of the phrase as a whole, but also with acceleration and deceleration within the ‘melody’, and this will again pose all sorts of questions and choices. I’ll chop the phrases up and combine them with each other. And I’ll find motifs that seem to be reoccurring; possibly a move or a line that seems to epitomise the identity of the material.

I will begin transposing some of the phrases, make versions on the floor, on the knees, maybe retrograde them (do backwards). Transposition is one area in which I sometimes take more of a backseat nowadays; I’ve done so much floor work and backwards material over the years that I am more interested in observing what the dancers do when they take this on. Because the material being transposed is already specific, the dancers will have certain rules and parameters that they will need to apply to their transposition.

While developing a specific vocabulary, possibilities to take the movement somewhere else will come up, and it is likely that I will start working on some new phrases based on what I have unearthed. This can mean I am working on three or four differing movement vocabularies at the same time. This is already the beginnings of crossing over to other styles that I will develop for other sections of the production, or perhaps not; I am being indulgent at this stage, almost developing movement for movement’s sake, simply exploring. I keep an eye on this, we are getting a motor running but I could go on indefinitely and this can get like handling too many ideas. If I set off on too much of a tangent my subject matter will become distant. My preparation is always questioning what I do, though I sometimes tell it to shut up because I feel I’m onto something as a pure ‘maker of movement’, a choreographer practicing, extending and developing vocabulary.

I always feel the floor when I dance, either under my feet or any other part of me that has contact with it. A phrase must find its grounding. I will make it heavy, too heavy, just to find where I am putting my weight, and build strength. We have hundreds of different muscles, bones; every movement will demand a different combination of these, and you have to train those muscles up so they can execute power and stability into the movement. A movement may gain so much power after doing this that it unleashes a jumping phrase. Any phrase made gently may become very fast or physical, and I want to know where I will be pushing from. The floor is your partner, you can’t dance without it, so use it. It is a very reliable partner. It is always there.

Say you are looking for a ‘hard’ phrase, something physically powerful, or maybe a fast phrase, or something full of anxiety. That doesn’t necessarily mean you should just catapult yourself into trying to get this based on a ferocious energy. Often a phrase that looks fast or hard in my work will have been made gently. Clear articulation will achieve a sense of speed, better than if you just race through a phrase with tension and no detail. I learnt early on in my dancing career, when asked to make very physical material and repeat it for long hours in rehearsals, that I had to find a way to do this without destroying my body. I saw how more experienced dancers around me were doing this, and I made sure that everything I made was organic. That doesn’t mean floppy or without using muscle or power. But I made clear pathways, and although the material was highly physical and could even appear dangerous when it eventually made it on stage, nothing was demanded of my body that it wasn’t designed to do. The body can move in so many ways; its design is pretty incredible. Dancing will always push physical limits, but with this facility there are all kinds of ways to produce and release power if you know it well enough. Look at what stunt men do.

I learnt a lot about phrasing from playing the guitar. Take a simple blues riff; you can play it in a million different ways. But then you get someone who plays it in a way that is unique and it changes the evolution of music. Jimi Hendrix did this. I can hear a traditional blues riff he played and think ‘I know the notes he’s playing, but how the hell did he make it sing like that…?’ This is true also with actors – the way they emphasise a word or line in a script can change its whole meaning, sometimes the meaning of a whole play or film. It is the same with phrases in dance. You have to experiment and be wise, recognise the possibilities and what the effect of implementing them will be. Some great choreographers work in a particular established style but it is the way they use that style that gives them a voice.

How long should a phrase be? I know when a phrase is a phrase; it speaks to me. You might not want punctuation – you might want a continuous flow – but always consider it even if you believe that we shouldn’t think in terms of phrasing at all and that it is all just a continuous line but if I just go on and on in this sentence without phrasing and punctuation after a while you’ll get lost and what I’m saying won’t be going in especially if I repeat myself too much… But, read Last Exit to Brooklyn; some passages don’t have any punctuation for pages, and they are brilliant. And they do have phrasing in that they have rhythm. It requires a combination of many elements to establish a phrase. Even if music is continuous (I’m not talking about a drone) you will hear phrases within it. Even if you want to make a continuous stream maybe establish where you think phrases are within it. Clarify them and I think you won’t lose the effect you want. In fact you will have improved it. Everything has phrasing. Listen to a birdcall, the gunning of a car engine. Listen to an actor reel off some fast text, but listen out for the phrasing. Normally you won’t be thinking about this because these decisions will be delivering what the actor is trying to say – the information and the emotion. Phrasing is like structure, a tool for manipulating an audience.

A little more about ‘clutter’. I have been writing for over twenty years. I wrote three novels and I threw them all in the bin (I’ve written books since then that I haven’t thrown in the bin), but those years of study were not a waste of time: learning the craft of communication with words informed my work in choreography. One of many things I learnt was how to remove clutter and how much better the writing is without it. Continually assess this because clutter is very good at hiding itself. It is very easy to over-choreograph; we can get carried away by ‘flow’ once we’ve hit on a vocabulary and are producing lots of movement with it. It is one of the most common traps to fall into in dance, especially these days with so many ways to move and some vocabularies that flow relatively easily. Well-crafted work will find a flow, then edit, question, audition, think of musicality, think of how one phrase can perhaps say more than ten. I got caught in this trap quite a few times early on in my career when movement was pouring out of me. I didn’t have the knowledge or experience to hold back on it.

After attention to all these details, what are my phrases now? Do I ‘feel’ they are saying what I want to say, or at least saying something? What are they saying to my outside eye? Maybe not what I wanted – wait, maybe they are but not how I expected. I was trying to capture something – have I done that? Is this really what I want to say? Am I already going back to my preparation – characters, narrative, music, structure, and questioning it? Now the process is really kicking off and the meter is running. All these questions need to be tackled now. I could be heading on a path I didn’t foresee.

The dancers and I give phrases names: ‘Scarecrows’, ‘The Spanish’, ‘Chickens’, ‘Trojans’, ‘Gypsy’; all kinds of things. Nowadays we film a phrase when we feel we are capturing it so that nothing is lost (this also prevents arguments when we come back to them). At first I am obsessed with what I am doing, finding, then I add the element of the artists learning the phrases with me because that is going to alter everything. Dancers are not machines, and isn’t that great? I always say my material is like a script you give to an actor. I will be specific about all aspects of the script – the details and the big picture, but it will be passed on to them for their interpretation and they will take it forward, and eventually I will give it to them. They will own it as they will own their character, their place in the work.

I won’t be finished with my initial work on a single phrase until I know every detail of it and have several phrases in the same vein. And then myself and the dancers will leave them be. Tomorrow they will have settled a little in everyone’s bodies, and we’ll start working on them again. I’ll start making some other phrases. Something completely different and go through all the same processes again. All this material goes in the ‘choreography bank’. Tonnes of it. The last session I did with my company we did this every day for two weeks straight. We had about forty minutes worth of material by the end, some of it already transposed, some thrown together into sequences, some tried with music, some duets sketched out. Importantly, I’ve started my creative choreographic process in the studio, begun the exploration of different choreographic vocabulary that might go into the production. At this time everything is scattered in one’s mind. This is normal. Have faith that this hard work is all worthwhile and something will form out of the chaos.

Right at the beginning of the rehearsal process I am considering my structure. I want to paint it in gradually as I go along, a bit here, a bit there, so I am growing an initial picture early in the process. I will want to have a very rough first draft, even if everyone else is reeling around, by roughly three to fours weeks into rehearsals, if not before. Even if I work on raw material fo...