![]()

TIBER ISLAND AND THE ANCIENT PORT

A southwest wind blew out of Africa. Behind it, at a slower pace, came Africa itself. The breeze cooled as it crossed the ancestral Mediterranean and picked up moisture. Slipping over the Apennines, which the African plate in its slow northeastward drift was heaving up, the clouds opened. Heavy rain drenched the bare slopes, eroding and channeling, crafting a system of west-flowing streams. Not far from the base of these raw mountains, some forty miles inland from the present coast of Italy, these new rivers—the Tiber among them—after a steep flight down mountain rock, flowed into a shallow bay of their natal sea.

About two million years ago the steady thrust from Africa cracked the sea floor beneath these shallow bays to open long parallel gashes. Molten rock from deep within the earth channeled to the surface through these fissures, and a string of volcanoes was born. The first erupted in Tuscany; then in a general southeastward trend, they burst from the ocean floor in a loose chain of conical mounds. The impulse went through the territory that would become Latium—the province of Rome—then angled in historic time toward Naples and Sicily. Vesuvius and Mount Etna are its latest offspring.

Spewing out lava, ashy dust, and rock, the volcanoes raised themselves above the water. Outflow measured in cubic miles gradually filled in the shallow coastal bays and made them plains of rock. The sea where the river once ended was driven south and west, and the Tiber followed. Charged with fresh waters from the volcanic slopes, it carved a new course through solidified ash and lava. For the most part it was an easy job. Water was abundant, and the newly minted rock proved soft and soluble. Working its way across the gently sloping plain in wide loops and meanders, the river carved a deep and spacious bed for itself. In time, the flat volcanic plain became a deeply etched, eroded canyon land. (1)

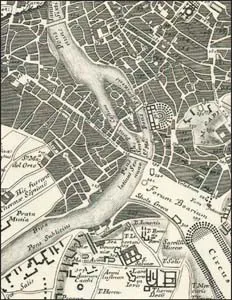

At a spot now some thirteen miles from the sea, the river came upon a hard tongue of rock it could not scrape or melt away. At what would become Rome, the Tiber split, leaving a rocky island in midstream while it coursed through shallow rapids on either side. A little south of this island a marshy side canyon opened to the east. The Romans named it the Velabrum. Another canyon intersected further downstream, striking a north-south line.

Having left behind this one irreducible island, the Tiber continued on its way toward the sea, fully mature, broad, deep, and impassable. Nearing the coast, it slowed, spawning dense mosquito-breeding marshlands that stretched for miles in every direction. For settlers who began moving into the region in large numbers some 3,500 years ago, the deep river and the hostile marshes along its edge formed a potent natural barrier. On its eastern margin Latin civilization took root. Latin towns dotted the Alban hills, the long-stilled volcanic cluster that had given birth to the region. Latin settlers occupied Rome as a frontier outpost sometime in the eighth or ninth century BC.

Across the Tiber from this Latin bridgehead, people known as Etruscans inhabited a wide swath of central Italy that extended from the sea inland to the Apennines and as far north as the Arno River, which flows through present-day Florence. The Etruscans, who gave their name to Tuscany, were more numerous, wealthier, and more powerful than the Latins. They were also more cosmopolitan, trading goods, techniques, and ideas with Greek colonists who had settled in Sicily and southern Italy.

The main point of contact between the Etruscans and the Latins was the first place up the Tiber from the Mediterranean where the river could be forded. The shallow rapids flanking Tiber Island made a rough but manageable passage for men and animals in all but the highest water. All contact and all commerce between the principal civilizations of central Italy funneled through this ford. The great peninsular footpath that linked the peoples of northern Italy with those in the south also crossed the Tiber here. And just here it intersected a path from the coast which took its name—Salaria—from the sea salt traded inland. Around this shallow ford and the wooden bridges that soon replaced it, the city of Rome found its source of life and wealth. (2)

“So much then, for the blessings with which nature supplies the city; but the Romans have added still others, which are the result of their good judgment. If the Greeks are to be honored for their achievements as builders of cities that are renowned for their wealth, beauty, security, and good harbors, the Romans must be counted superior in matters to which the Greeks gave little thought: the construction of roads, aqueducts, and sewers that wash out the filth of the city. They have so constructed the roads that run throughout their country by cutting through hills and building up valleys, that their wagons can carry boatloads of goods. Water comes to the city in such quantities that veritable rivers flow through the city and the sewers; almost every house has cisterns and water pipes and abundant fountains. The sewers themselves, vaulted with close-fitting stones, have room in some places for wagons piled with hay to pass through them” (Strabo, Geography 5.3.8).

Standing today at the river’s edge, you would never imagine yourself to be in the bottom of a wide canyon at its point of intersection with narrower side canyons. You seem to be standing on level ground and looking up at modest hills that rise above the wide river plain. All the same, the celebrated Seven Hills of Rome are really the uneroded remnants of a volcanic plain seen from the prospect of the river that dissected it. A matter of perspective, but since the river and this island within it are the city’s nucleus and its most ancient rationale for being, it is wise to adopt the river’s point of view.

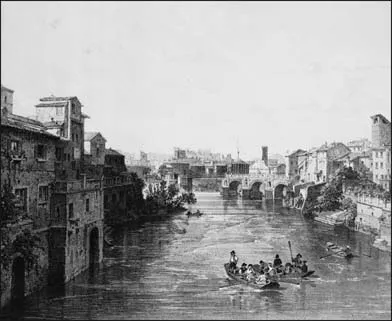

Empathy with the Tiber in other matters is more difficult. Like all too many urban rivers, it lies far below street level in a deep and narrow chasm, visible from above but almost out of reach. Steps lead down to broad pathways at the river’s edge, but until recently almost no one strolled along them, even on those rare occasions when they had been cleaned of silt and weeds. (3) In an effort to draw Romans back to their river, the city has attempted to spruce up the sidewalks, adding artwork and even an artificial beach near the Vatican. Sightseeing boats, loaded with tourists, now travel through the center of the Eternal City.

This radical containment of the Tiber is tribute of a sort, a measure of the river’s power and a veiled testimony to its role in carving the ground on which the city stands. Most of Rome still lies in the Tiber’s natural floodplain. Throughout the city’s long life, the unrestrained river repeatedly submerged it. Plaques on the façade of the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and in other places around the city record the high-water marks of past floods. More than 130 major floods have been recorded in the city’s 2,700-year history. In 1870, the year Italy became a nation with Rome as its capital, an especially devastating flood led to a long-range plan, which was completed in 1900. Today, the river that shaped Rome and gave it life is contained behind barriers bigger than those the ancient Romans built to keep the barbarians out. Romans call these Tiber embankments I Muraglioni, The Great Walls. The river was channeled and contained within these steep confines. Levees were built along both banks, some as high as twenty feet above street level. River life ended, and a Berlin Wall divided ancient neighborhoods. Tree-lined avenues were designed at the levee tops, but they were too remote from the river to serve as the greenways their designers imagined. Now these wide roads are mobbed with traffic that further isolates the river.

The one spot in Rome where people and the river still seem to be on friendly terms is Tiber Island. The river is at its widest there, and its confining walls are far apart. The point of the island that breaks the current has been streamlined and merges with the piers of the modern Ponte Garibaldi, but the downstream end is welcoming. The pavement at the river’s downstream edge has grown to the scale of an urban beach. There are even a few straggling plane trees. People sun themselves here; they walk along or sit and listen to the river. It is the one spot in Rome—a city of fountains—where the sound of rushing water completely drowns out the noise of traffic.

Ochre-painted walls and oddments of brick and stonework support the buildings above; a solitary square tower guards them. Moated by the river, the densely built-up island has the look of a romantic medieval town. Of the island’s substance—the stolid lava core with its sand and silt accretions—nothing at all can be seen. Both the medieval walls and modern flood control cover the island like a synthetic crown over an ancient tooth. The most prominent surviving features of the island the Romans knew are the two ancient bridges that connect it to the mainland, a third ruined bridge below, and a sculpted ship’s stern at its downstream end.

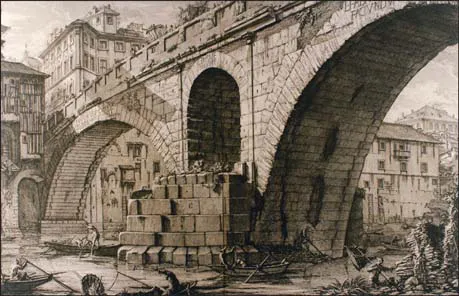

The Pons Fabricius, one of Rome’s most celebrated and picturesque bridges, carries on the work of the prehistoric river ford as it links the island to the Latin shore. (4) Built in 59 BC as part of a general restoration of Tiber Island, the bridge is Roman in every way. The stone from which it was built was created by the same volcanic eruptions that laid the groundwork of the city itself. The bridge’s structure embodies the most characteristic Roman architectural technique, the keystone arch. Despite surface differences, the companion Pons Cestius, which links the island to Trastevere, shares these characteristics. Though one is faced with brick and the other with a marble-like stone called travertine, the muscle and bone of the two are the same. On the underside of either bridge the vaults, which are made of large, close-fitting blocks of a gray volcanic stone called peperino, are identical. Travertine blocks carefully tied into the stonework of the central span rim and reinforce each vault.

The volcanic eruptions that put the ground under Rome’s feet made the Roman countryside a supply yard of building materials. For much of the city’s history it has subsisted entirely on this domestic store. The earliest Roman buildings were made with materials quarried inside the city itself, and much of the soft rock beneath Rome is warrened with caves, pits, and tunnels. As the political and military power of the city expanded, higher-quality building materials from an ever-widening area were substituted. The peperino in these bridges, the product of a late volcanic eruption, was quarried in the Alban hills. The marble-like travertine, formed by mineral-rich secretions from volcanic hot springs, came from Tivoli, where it is still quarried today. Both stones are easily worked, strong, and durable. Travertine stands up especially well under compression, and it is often used at points of stress where load-bearing is essential. As Rome’s power expanded, the city gained access to building materials from the whole Mediterranean basin. In its most powerful periods, exotic imports like marble, granite, and porphyry supplanted the local stone.

Like all Roman monuments, these bridges embodied the three characteristics that the Roman architect and theoretician Vitruvius, in De Architectura, identified as essentials of Roman building. All structures, he declared, both private and public, built simply for pleasure or dedicated either to the common welfare or the cult of the gods, needed to manifest firmitas (stability and endurance), utilitas (usefulness), and venustas (beauty of materials and proportion). The bridges show how much Roman engineers knew about firmitas in the face of the river’s power. The central support is pointed on its up-river side into a chisel-like cutwater that breaks the force of the current and shears off floating objects. The gentler curve of the downstream edge counteracts undercutting by backward swirling eddies. The arched opening in the central support of Pons Fabricius reduces the lateral thrust of floodwaters. It is the arches of the bridges, though, which are their most impressive and most characteristic feature. Though the stones forming them are not cemented together (their surfaces have been pointed up with mortar in modern times), each semicircular arch spans nearly seventy-five feet. This wide span lifts the roadway well above flood level and reduces the number of piers in the water. Temples and monuments might be more eye-catching, but they lack the harmony and balanced tension of these bridges.

Architectural historians are uncertain whether the Romans invented the arch on which these bridges, like so many Roman structures, are based. It may be that they learned to build and use it from the Etruscans. Roman mastery of its principles and devotion to its use are undisputed. As gravity pulls down, the flared upper end of each wedge-shaped block in the arch squeezes the stones to either side. This redirected force travels sideways along the curve of the arch and into the supporting piers. The central keystone works in the same way as all the other stones in the arch.

The island “between the bridges,” as an ancient Roman map described it, has a curious history of its own. In the third century BC a new myth transformed the ancient crossroads. The story of how the healing god Aesculapius came to Italy and chose Tiber Island for his sanctuary was a favorite one, and it was repeated many times. This is a short version of the story as an unknown Roman writer told it: “Once when Rome was stricken with a plague, the Romans, following the advice of an oracle, sent ten men headed by Quintus Ogulnius to the shrine of the healing god Aesculapius in Epidauros. While the men stood admir...