![]()

Urban Space as a Reflection of Society

Experiences of our own “inhospitable” cities have made us more aware of the appearance of urban environments and their effect upon the people who inhabit them.* The city as living space has become the focus of intense discussion in the past two decades, and the debate has revealed how close the connections are between a given community’s economy, social conditions, health, and culture on the one hand, and the appearance of its cities on the other. In the course of only one generation the prevailing views and values have swung from one extreme to the other in Europe, from the modernization of inner cities to accommodate ever more automobiles to the creation of large car-free zones; from the heyday of commuter zones, suburbs, and city centers depopulated in the evening to their revival through construction of downtown entertainment complexes, shopping centers, and luxury apartments.

Discussion of these pressing contemporary issues has had a highly stimulating effect on historical studies. The topic of the city has been very popular for some time now, and among the many new approaches one of the most fruitful and appealing has proved to be the attempt to provide as complete a description as possible of a city’s total appearance in a particular historical period. This approach seeks to interpret the entire physical and aesthetic configuration of a city as a reflection of the condition and mentality of the society that inhabited it. The aim is to understand how its layout, architecture, and visual imagery of all kinds work in conjunction with citizens’ rituals and everyday activities to make up a single coherent structure expressive of a society’s needs, values, expectations, and hopes.1

In cases where a substantial amount of evidence has survived, townscapes have a great deal to tell us. This is especially true where growth was organic and the city’s face not created through the will of a single ruler or ideological program, for then the city represents the realization of many anonymous and in part contradictory interests. In a largely self-regulating process—as these interests interact and the participants make decisions based on specific needs, pressures, or personal preferences—inhabitants produce a configuration that becomes a self-portrait of their society, although this was by no means the intent.

Once a cityscape has been established, no historian will underestimate its effect on the mental outlook of its inhabitants. Repeated daily experience of one urban environment can be socially integrative, stabilizing, or even stimulating, while another may arouse feelings of irritation or insecurity, or undermine the citizens’ general sense of well-being. In the case of ancient societies, one need only think of the antithetical vistas of late Republican and Augustan Rome, or the effect of the public monuments erected on the Athenian Acropolis in the age of Pericles, or the crumbling public edifices in the city centers of the late Empire. At the very least cityscapes understood in these terms certainly constitute an integral part of the culture of each period.

Pompeii, the best preserved Greco-Roman city, presents great difficulties to archeologists wanting to approach it in this manner, for in fact we can see only the city that was buried on August 24, A.D. 79. Since it was more than six hundred years old at the time, we are forced to imagine what the earlier buildings looked like in their original state and ask what purpose they served at the time of their construction. Many elements of former cityscapes were no longer visible in A.D. 79, yet the sheer numbers of buildings preserved by the eruption, both those already uncovered and those still buried, have (with a few exceptions) prevented the type of stratigraphical excavation normally undertaken at other sites.

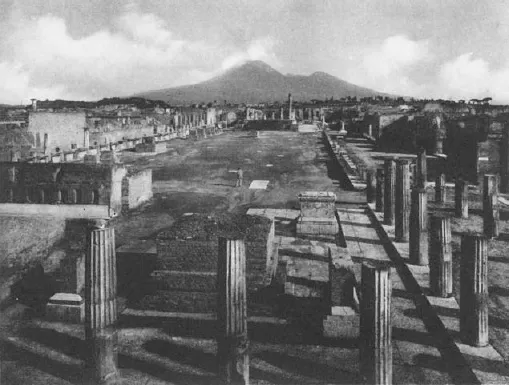

Figure 1 The forum, as it appeared after the earthquake of A.D. 62. The current state of the ruins is confusing, since most of the structures in the forum had not yet been re-built at the time of the eruption that buried the city. The Pompeians had cleared away the rubble and removed valuable materials such as marble slabs and decorative statuary, some of which was re-used in private houses. The fact that this public quarter with the town’s most important temple and the basilica had not been rebuilt seventeen years after the quake, although construction had begun on a large new bath complex, gives an indication of the priorities set by the town council (ordo) at the time. Some of the valuable materials appear to have been “excavated” by the former inhabitants of Pompeii after the eruption.

We must also take into consideration the fact that Pompeii was not a typical ancient city. The majority of its structures, especially the public buildings, had been devastated by a severe earthquake on May 2, A.D. 62, and perhaps another in the seventies, and still lay in ruins.2 This explains why present-day visitors find a number of buildings, particularly around the forum, so lacking in vividness and immediacy, especially in contrast to the houses that have been reconstructed (fig. 1). Not only have the forum buildings been stripped of all the carved marble decorations they displayed before the first earthquake; their present state also gives no impression of the full height of the walls or the effect of the structures as a whole.

Traditional approaches to studying Pompeii have also tended to ignore questions about historical contexts and the city’s architectural evolution. From the time when excavations began in 1740, researchers’ work was dominated first by aesthetic interests and later largely by the school of historical positivism. Pompeii and Herculaneum became the chief sources of our knowledge of ancient material culture, and investigators concentrated on classifying the materials they found according to genre and function.

When the remote past becomes palpable in the immediate present, the effect is fascinating, and every day thousands of visitors to the ruins gain the impression that, all in all, human beings remain basically the same throughout the ages. Pompeii is more conducive to such feelings than other sites, yet to experience the past as essentially familiar rather than as alien is a fatal error for historians.

Beginning with the standard works by Overbeck and Mau, most published studies treat Pompeii topographically, and they provide admirable examples of this approach. As a result, however, virtually no attempts have been made up to now to acquire an overview of the whole city and to distinguish the various historical layers in its fabric. The history of Pompeii continues to be written as a history of individual structures, providing little or no sense of larger connections.

In what follows, at least as far as public buildings are concerned, I shall seek to identify and differentiate three historical aggregates: the Hellenized Samnite city of the second century B.C., the period of rapid change following the founding of the Roman colony in 80 B.C., and the new townscape of the early Empire. I am grateful for a wealth of specialized archeological and epigraphical studies that have appeared in the past two decades; it is owing to their many new findings that such an attempt has become possible. The results—mainly pertaining to genres in the field of archeology and to social and economic history in epigraphy—will be evaluated for their relevance to the approach here, which is to seek a historical synchronicity of culture and mental outlook. Such an approach necessarily gives less priority to the examination of individual monuments, as the aim is rather to demonstrate that particular features common to quite different monuments can be interpreted as indicators of specific historical situations and cultural trends. I have striven to be as precise as possible, although space constraints may have led to some occasional simplification in presenting the material.

We still know very little about the first four hundred years of Pompeii’s history. The most recent studies by Stefano de Caro indicate that a first wall of tufa and lava, surrounding all 157 acres of the lava plateau on which the town is situated, dates from the sixth century B.C.3 In the early fifth century it was followed by a limestone wall, which lay outside the Samnite ramparts (end of the fourth century B.C.). The first wall might reflect an Etruscan attempt to link a number of villages and protect the strategically and economically important site at the mouth of the River Sarno from encroachment by the Greek settlers in Campania. In the course of only a few decades a small town center with the temple of Apollo (the “old city”) sprang up on the site that later became the forum, and a Doric temple was built on the Triangular Forum. But by far the greatest part of the area enclosed by the walls appears to have been used for agricultural purposes.

On the basis of pottery finds scholars have inferred that a period of relative prosperity and lively trade occurred in the second half of the sixth and in the early fifth century B.C., followed by a definite decline until the end of the century. The small settlement on the arid lava spur must have languished until the Samnites emerged from their mountainous inland territories in the late fourth and third centuries and settled in the towns of the coastal plain. A portion of the surviving walls, the oldest limestone houses, and the layout of the street grid in the northern and eastern sectors of Pompeii date from this time and reflect a renewed upsurge of prosperity. No public buildings from this period have survived, however. After the Second Punic War there appears to have been a large influx of new settlers; this is suggested by the numerous simple houses without atria in region I that have been studied in recent years.

From the time of the Samnite Wars, Pompeii was an ally of Rome and required to participate in Roman military campaigns, although the town was left to manage its own internal affairs. The language spoken in Pompeii was Oscan. Not until the late second century B.C. do we have a clear enough picture of the city to gain a sense of its specific cultural identity.

The Hellenistic City of the Oscans

The Oscan city of the second century B.C. is marked by great private wealth and efforts by the upper class to acquire the Hellenistic culture that would link them to the larger Mediterranean world. Although the Romans had expanded their overseas empire into the western and eastern Mediterranean, their Italic confederates remained excluded from Roman citizenship and thus from full participation in power. These circumstances allowed the more affluent residents of the towns in central Italy and Campania to concentrate their energies on increasing their wealth. They did so mainly by increasing agricultural production and exports.4

From about 150 B.C. the leading families of Pompeii were clearly able to amass large fortunes, chiefly owing to the wine trade, but perhaps also to some extent to the production of oil. Amphorae and seals characteristic of the region document the export of wine by Campanian families to places as far away as Gaul and Spain. Production on this scale could be achieved on medium-sized estates by employing slave labor and using the improved methods of c...