When 15-year-old Kathy Kohner tried to join the exclusively male band of surfboarding fanatics at Malibu Beach, she got a distinctly chilly reception. She was a girl, and what’s more, a small one—barely five-foot tall and only 95 pounds soaking wet. But Kathy was persistent and she finally won her way to the surfers’ circle, winning also the name of ‘Gidget,’ a combination of girl and midget.

One day I told my dad that I wanted to write a story about my summer days in Malibu: about my friends who lived in a shack on the beach, about the major crush I had on one of the surfers, about how I was teased, about how hard it was to catch a wave—to paddle the long board out—and how persistent I was at wanting to learn to surf and to be accepted by the ‘crew,’ as I often referred to the boys that summer.

(Zuckerman 2001: ix)

Kathy Kohner wanted to write a memoir about her personal feelings and experience. However, noting that her father was a screenwriter at the time, Kohner says, ‘He told me he would write the story for me.’ Despite their differences, both versions of the story, Life’s and Kohner’s, describe a form of larceny—of Kathy’s story, her voice, and her experience—by her father.2

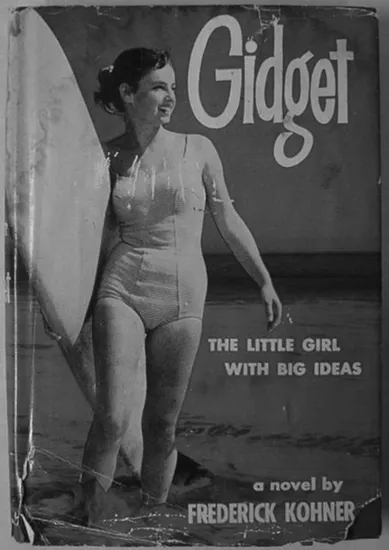

Undoubtedly, Frederick Kohner’s decision to write Gidget: The Little Girl With Big Ideas stems from his career as a screenwriter. Kohner was born near Prague in Teplitz-Schönau, Austria-Hungary (now the Czech Republic). He studied at the University of Vienna and got a PhD at the Sorbonne, writing about film as an art form in a thesis titled ‘Film is Poetry’ (Champlin 1986). He became a newspaperman in Prague then moved to Berlin to work as a screenwriter in the film industry. In 1936, he fled the Nazis and went to Hollywood, where his brother Paul had been working as a film producer and then started a talent agency (Yarrow 1988).3 Prior to writing Gidget, Kohner had worked on about twenty Hollywood films, sometimes uncredited, sometimes writing the original story, sometimes working as one screenwriter among many.

Read as an act of masculine appropriation, the novel Gidget is somewhat disconcerting. Inasmuch as Frederick Kohner took over the role of author from Kathy Kohner, the novel itself ventriloquizes Gidget’s voice and inscribes her as author. In fictionalizing Kathy Kohner’s story, her father writes a first-person narration in the voice of Gidget, here marked as author of her own story: ‘I’m writing this down because I once heard that when you’re getting older you’re liable to forget things and I’d sure be the most miserable woman in the world if I ever forgot what happened this summer’ (Kohner 2001: 3). The story that Gidget tells is partly about surfing and also, suggestively, the story of her sexual desire. Gidget describes herself as ‘really quite cute’ and notes that she has ‘a couple of really sexy-looking bathing suits,’ but says that ‘the only thing that worries me is my bosom’ (Kohner 2001: 10). She describes feeling ‘all hot inside just thinking about’ surfing, writes ‘long and passionate’ letters to a crush, and has ‘thoughts so startlingly romantic and biological that they surprised and shocked me’ (Kohner 2001: 61, 139).

For Ilana Nash, Frederick Kohner’s appropriation of Kathy Kohner’s story (and the erotics he imbues it with) link Gidget to Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955) as a more covert version of the ‘sexy daddy’s little girl’ narrative (2002: 341, 2006: 212). Nash decries the ‘voyeuristic pleasure of reading a girl’s memoirs, offering a peek into her private life’ as exploitative (2002: 349). Indeed, knowing that the character is based on the author’s daughter, there is something potentially creepy and prurient about Gidget. One winces when the Los Angeles Times describes the novel’s origins as a ‘Cinderella story’ and asserts that ‘Cinderella’s Fairy Prince turned out to be her father’ (Marsh 1957).

Moreover, as Nash suggests, as a screenwriter, Kohner dipped into some complex daddy-daughter waters. In It’s a Date (Seiter 1940), for which he wrote the original story, mother and daughter not only compete for the same part in a play but also both romance the same man. In Mad About Music (Taurog 1938), which won Kohner an Academy Award nomination, a young girl makes up stories about an imaginary father who is an explorer and adventurer, then meets an Englishman and convinces him to play the role. In Three Daring Daughters (Wilcox 1948), three sisters who have just graduated school attempt to reunite their estranged parents and stop their mother’s relationship with a new man.

Nash’s reading of Gidget: The Little Girl With Big Ideas in relation to Lolita and other ‘sexy daddy’s little girl’ narratives relies on auteurist and biographical readings. According to this logic, because Frederick Kohner is father to the real-life Gidget, and because Kohner has written some screenplays about girls and fathers, the character Gidget’s sexual explorations seem tinged with ‘daddy’ issues. Auteurist claims for Kohner’s screenwriting, however, are complicated when one examines the production context of the films he scripted. It’s a Date credits two writers besides Kohner—Jane Hall and Ralph Block—for the original story and attributes the screenplay to Norman Krasna. While Kohner gets an Academy Award nomination for the original story of Mad About Music, he shares credit for the story with Marcella Burke. Two other writers, Bruce Manning and Felix Jackson, wrote the screenplay, and two more uncredited writers worked on the treatment. On Three Daring Daughters, Kohner is listed second among four writers, including the first, Albert Mannheimer, plus Sonya Levien and John Meehan. All three films are musicals with three separate directors. It’s a Date and Mad About Music are both Universal Deanna Durbin vehicles and thus are framed as star vehicles, working within assumptions of innocence and purity attributed to the teen star. Three Daring Daughters is a clumsy late vehicle for Jeannette MacDonald and part of MGM’s dogged efforts to showcase José Iturbi, serving the demands of at least two star images. While a superficial description of the plots in these films hints at a daddy-daughter theme, the complexity of the films’ authorship makes it difficult to claim Kohner as the primary author or even to assess his influence.

Looking across Kohner’s career, it seems that these films are less representative of an auteurist vision and more symptomatic of his journeyman ability to write light comedy and self-reflexive musicals, the majority of which would not fit Nash’s ‘sexy little daddy’s girl’ category. These include Johnny Doughboy (Auer 1942), a late Jane Withers vehicle about look-alike musical performers (one nice and one nasty) that allows Withers to play two roles; Patrick the Great (Ryan 1945), starring Donald O’Connor, with a father-son musical plot in which the son and father are both up for the same role; Pan-Americana (Auer 1945), a South American wartime love triangle plot described in ads as ‘the Happy-Go-Lucky Latin Musical’; Tahiti Honey (Auer 1943), a Tahitian wartime musical, starring Dennis O’Keefe; or Never Wave at a WAC (McLeod 1953), where a society matron (Rosa-lind Russell—hardly a girl in 1953) joins the WACs. Further complicating any claim for Kohner as auteur, many of these Kohner-scripted films are directed by John H. Auer, a fellow Austrian émigré who specialized in B musicals and crime dramas at Republic and RKO, and who both directed and produced these films.

Moreover, even if we could read Kohner as an auteur and consider daddy-daughter themes as a major theme in his work, the narrative of the novel Gidget itself does not invite such a reading. While Gidget is exploring her sexuality and desire, her attention is directed solely at young men and boys, and her character’s father’s interest in her is not inappropriate. In a crucial distinction from Lolita, events are filtered through Gidget’s point of view, memory, and emotions, not those of her father. Where the narrative does support a biographical reading is in Kohner’s depiction of Gidget, like Kathy Kohner herself, as a daughter of a naturalized Austrian émigré. Christened Franzie (Kathy Kohner’s mother’s real name), from the German name Franziska, ‘after my grandmother,’ the novel’s Gidget refers to her father—a professor of German literature at the University of Southern California—as ‘only a naturalized citizen’ and therefore prone to clichés (Kohner 2001: 28, 11, and 24). The father is thus invoked less in a fetishistic way than introduced to be dismissed, in a way typical of both teen girls and second-generation immigrants. While there is an element of voyeurism in Gidget: The Little Girl With Big Ideas, the novel, as I will discuss later, does more than titillate. Certainly, it deals with teenage female sexuality and desire, but it also ascribes agency to Gidget, in writing her story and in pursuing her dream of surfing.

As with Kohner’s screenwriting, the novel Gidget needs to be read in terms of its production and reception context. Kohner’s novel has been compared to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, as bestsellers from the same year and as texts about countercultural types (surfers and Beats, respectively).4

However, On the Road and Gidget are distant cousins at best. Both are first-person narratives that can be taken as fictionalized versions of real events, and both take place in a subcultural milieu. But where Kerouac’s narrator, Sal, is himself a writer, and a good one, Gidget complains about how hard writing is as she quotes advice from her high school comp teacher. ‘So the longer I sat there and thought about this writing business, the more I realized it wasn’t for me,’ she states ironically as she goes on to ‘write’ the novel (Kohner 2001: 6). Kerouac’s narrative is resolutely masculine, even misogynist, and consists of sprawling, wide-flung adventures with a vast cast of characters in decadent circles with frequent sex, theft, drinking, and drug use. In contrast, Kohner’s narrative presents a youthful, feminine point of view, focuses on a very small cast of characters, takes place in a very small sphere of action, and despite the link to surf culture, is fairly mild mannered in its portrayal of a subculture.

Reviews and commentary of the time definitely did not link the two books. In contemporary reviews, Kerouac is ‘a writer of such power,’ linked to Walt Whitman, Thomas Wolfe, Nelson Algren, Saul Bellow, Ernest Hemingway, Carl Sandburg, and F. Scott Fitzgerald; and his writing is described as ‘authentic,’ ‘a stunning achievement.’ A review in the Washington Post proffers that Kerouac will ‘blast his own niche in the pyramid of American letters’ (Browne 1957). Reviewers use words like ‘frenetic,’ ‘plotless,’ ‘experimental,’ ‘a documentary of frenzy’ (Hutchens 1957; Browne 1957; Dempsey 1957). Gidget, in contrast, is described as ‘a little novel,’ ‘pleasant,’ and ‘touching and entertaining’ (Kirsch 1957; J.C. 1957; Kielty 1957). Reviews mainly focus on the plot of Gidget, citing only the ‘unquestionably authentic dialogue’ in the book but attributing it to Kohner’s being the father of two daughters. Where reviewers describe Kerouac’s characters as ‘neurotic, ‘bizarre and offbeat,’ and ‘bohemian,’ Gidget is characterized as a ‘nice—for a change—teen-age girl’ and ‘the surf bums are pretty nice, too’ (J.C. 1957). If Kerouac is taken to be the voice of the ‘sad,’ ‘depraved’ Beat Generation, Gidget is seen as embodying the ‘slightly hysterical world of the teenager’ (Hutchens 1957; Dempsey 1957; Kirsch 1957). To be sure, the different descriptions align with stereotypical distinctions between masculine and feminine texts and, concomitantly, between what is perceiv...