- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ergonomics In Computerized Offices

About this book

"Ergonomics in Computerized Offices should be required reading for office managers, union representatives, engineers, designers, or anyone employed in implementing a computerized office or improving conditions in an already computerized office...an excellent addition to any personal library."--Human Factors Bulletin

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. The Present Metamorphosis of Offices

A retrospective glance

The tremendous growth in computing and the whole area of information technology has already been well described in several books and many journals. In fact, developments and implementation in this area are very recent. Stewart (195) reports that one of the earliest computers used for commercial administration in England was the ‘Lyons Electronic Office’, which started regular work for the Lyons Tea Shop Company way back in 1952. In the first period, lasting about 15–20 years, all information was entered into the computer through punch cards and the results were printed on paper. This rather slow procedure was replaced by keyboards and cathode ray tubes (CRTs). The keyboards greatly increased the speed of feeding information into the computer and the cathode ray tube—the main element of the visual display terminal (VDT)—gave the results immediately to the operator.

In the same period the first three generations of basic components of the computer were developed: the valve, the transistor and the large-scale integrated chip. A fourth generation, very large-scale integration, is already well advanced. This enormous growth in power and speed as well as the reduction in size and cost have led to a tremendous spread of computer machines and information systems. And so the ‘age of information’ is beginning.

Parallel to the development of basic components a rapid change in office technology is evident. New generations of equipment seem to spring up nearly every month, each offering leaps forward in performance and ease of use.

A glimpse of the future

The US National Academy of Science (153) estimated that the number of VDT operators in the United States was approximately 7 million in 1980, with about 5–10 million terminals in use.

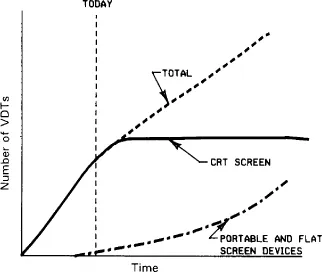

According to Korell (108), the growth of VDTs in offices will continue. He anticipates that VDT use itself will begin to taper off in the next decade as portable and flat screen devices equipped with liquid crystal displays come into their own, but the overall penetration of computer displays into the office will continue to grow sharply for the foreseeable future. Figure 1 shows these trends.

Figure 1 Trends in growth of VDTs in offices.

VDT use will gradually slow down as new display types become available, but total display use will continue to grow. According to Korell (108).

The traditional keyboard will to some extent be supplemented by touch pads, activated surfaces and voice entry. Office noise might become a new delicate problem, since voice entry will require lower noise levels.

The information age

The ‘industrial age’, beginning in the 19th century, increased the physical power of mankind as the machines enhanced or replaced human muscular capabilities. The physical strain of human work was greatly reduced. The information age is having similar effects on mental work: information technology can enhance or replace mankind’s intellectual powers and capabilities. Communications hardware and techniques are becoming vastly more complex and a critical element of the office. Fibre optics will increasingly connect computer networks and other communications hardware. These technologies are likely to continue to flood offices at an accelerating rate. There will be less centrally located, shared equipment and more individual workstations, which can already be observed today with the widely used personal computers. Most probably the number of ‘knowledge’ workers will increase and fewer clerical and support workers will be required.

It is unlikely that ergonomics will become redundant in the office of the information age. In general, experience has shown that with increasing productivity the intensity of human work increases. The load on the sensory organs and mental functions, environmental problems and constrained postures are likely to remain challenges for ergonomics in the future, too.

Traditional working conditions

As already mentioned, VDTs are at present invading all types of offices. They are entering a world where machines have not been used before. The result is a considerable change to offices and in working conditions. To call the present change a metamorphosis, similar to that known for caterpillars and butterflies, is hardly an exaggeration.

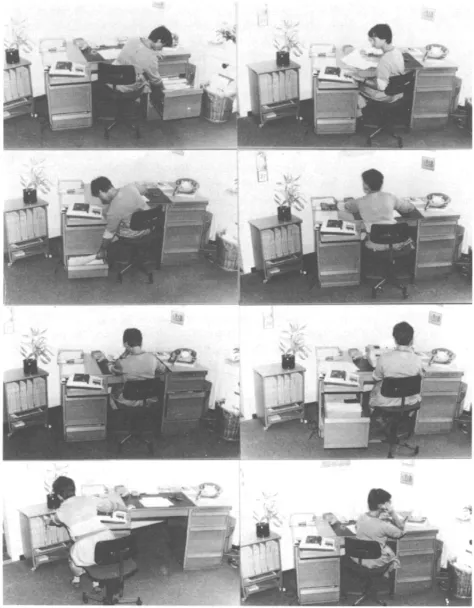

At the traditional office desk an employee performs a great variety of physical and mental activities and has a large space for various body postures and movements: he/she might look for documents, take notes, file correspondence, use the telephone, read, exchange information with colleagues, or type for a while, and he/she will leave the desk many times during the course of the working day. Figure 2 illustrates the variety of activities in a traditional office job. A desk which is too low or too high, an unfavourable chair, insufficient lighting conditions or other ergonomic shortcomings are not likely to cause annoyance or physical discomfort. The wide choice of activities greatly reduces or precludes the adverse effects of continuous physical or mental loads of long duration.

Man—machine systems

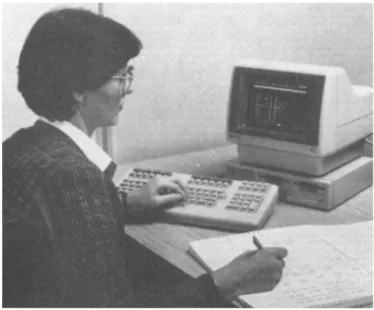

The situation is, however, entirely different for an operator working with a VDT for several hours without interruption or perhaps for a whole day. Such a VDT operator is tied to a man—machine system. His/her movements are restricted, attention is concentrated on the screen and the hands are linked to the keyboard. Figure 3 illustrates this link between the operator and the VDT workstation. These operators are more vulnerable to ergonomic short-comings, they are more susceptible to constrained postures, poor photometric display characteristics and inadequate lighting conditions. This is the reason why the computerized office needs ergonomics—the VDT workstation has become the launch vehicle for ergonomics in the office world.

Reports on discomfort

For as long as engineers and other highly motivated experts operated VDTs, nobody complained about negative effects. However, the situation changed drastically with the expansion of VDTs to workplaces where traditional working methods had formerly been applied: complaints from VDT operators about visual strain and physical discomfort in the neck—shoulder area and in the back became more and more frequent. This has provoked differing reactions: some believe that the complaints are highly exaggerated and mainly a pretext for social and political claims, while others consider the complaints to be symptoms of a health hazard requiring immediate measures to protect operators from injuries to their health. Ergonomics as a science stands between these opposite poles; its duty is to analyse the situation objectively and to deduce guidelines for the appropriate design of VDT workstations. This is also the main purpose of this book.

Figure 2 At traditional office desks employees carry out many different tasks and therefore have a large space for various body postures and movements.

Figure 3 The VDT operator is tied to a man-machine system.

Attention is concentrated on the screen, the hands are linked to the keyboard; constrained postures are inevitable.

2. VDT Jobs Seen through Ergonomic-tinted Spectacles

There are many different types of clerical jobs in which VDTs are used. But from the point of view of ergonomics it is possible to distinguish five kinds of jobs, characterized by predominant modes of interaction with the VDT:

- Data-entry work

- Data acquisition

- Conversational or interactive communication

- Word processing

- Computer-aided design (CAD) or computer-aided manufacturing (CAM).

Data entry

Data-entry work is characterized by a more or less continuous input of information through the keyboard into the computer. The operator’s gaze is mainly directed towards the source documents, looking only occasionally at the keyboard or the display for periodical control of progress. The eyes focus on the text of the source document, but in some cases the display remains in the visual field. Operators mostly use only the right hand to operate the keyboard, while the left hand handles the source document. Constrained postures are frequently observed in these jobs. The working speed is usually very high and 8000–12 000 strokes per hour is not exceptional. Data-entry work is repetitive and often montonous.

Data acquisition

Data acquisition or date enquiry involves calling up information from the computer and reading it from the display. Sometimes reading is associated with a search for some specific information. The attention is directed to the screen, sometimes also to the keyboard and source documents. A typical example of data acquisition is the job of telephone information operators. Starr (192) studied a large group of directory enquiry operators who retrieved directory listings on VDTs. These operators spent nearly all their working hours looking at the screen.

Conversational tasks

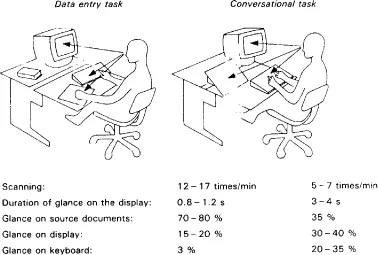

Conversational or interactive jobs involve both data entry and data acquisition. The operator enters data, which are usually more complicated than those in data entry activities, through the keyboard into the computer and watches the results appearing on the display after a certain time delay. These jobs are characterized by a dialogue between the computer and the operator who has some opportunity for making decisions. At conversational terminals the gaze of the operator alternates mainly between source documents and the display. Some reports roughly estimate that the view is oriented about 50% to the source documents and 50% to the display. Elias and Cail (51) recorded the viewing times in a conversational job, shown in Figure 4. The keyboard is operated with both hands and the speed of strokes is low. Airline reservation or airline space control as well as many occupations in banking are typical examples of conversational tasks.

Word processing

Word processing comprises text entry, text recall, controlling text for errors, keying in corrections and designing the layout. Secretarial tasks in document preparation and similar operations as well as formatting, proofreading and editing are frequent applications of word processing. The keyboard is used as in normal typing and the screen is watched for a large part of the working time.

CAD and CAM

Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) are techniques using computers for engineering purposes. Predominant applications include mechanical design, printed circuit-board design and electrical schematics. These tasks were formerly carried out by technical draughtsmen using drawing boards. At the design terminal the engineer develops a product in detail, monitoring his work on a graphic video display. The basic workstation elements are the graphic display, a digitizer command tablet with a pen or a ‘mouse’ as a cursor control and an alphanumeric keyboard used as a data or command entry device. Activities at CAD or CAM workstations could also be considered as conversational tasks. The worker’s control over the job task is great; CAD activities are considered interesting and challenging.

Visual scanning

VDT jobs have seldom been systematically analysed and compared with non-VDT jobs. An interesting analysis was conducted by Elias and Cail (51) who studied the visual scanning at a data entry and a conversational task with the NAC eye recorder equipment. These results are shown in Figure 4.

In the data entry task the operators glance at the screen from time to time, while their eyes are chiefly directed towards the source documents. In the conversational job the operators rarely change their direction of sight and their eyes are focused on the display for much longer periods. In a group engaged in data acquisition the time spent looking at the display came to a mean duration of 80% of the working time with glances lasting up to 135 s.

Figure 4 Frequency of scanning and duration of the gaze fixed on the screen in a data entry and in a conversational task.

The percentages refer to the approximate duration related to the working time. According to Elias and Cail (51).

Work-sampling in CAD

van der Heiden et al. (84) carried out a work-sampling study on CAD workstations to determine the relative use of the keyboard, digitizer tablet and screen. Thirty-eight workstations with different engineering tasks (mechanical design, printed circuit-board design and electrical schematics) were involved. The results are shown in Table 1.

The...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Author’s Acknowledgement

- 1. The Present Metamorphosis of Offices

- 2. VDT Jobs Seen through Ergonomic-tinted Spectacles

- 3. Physical Characteristics of VDTs

- 4. Vision

- 5. Ergonomic Principles of Lighting in Offices

- 6. Visual Strain and Photometric Characteristics of VDTs

- 7. Ergonomic Design of VDT Workstations

- 8. Noise

- 9. Occupational Stress, Work Satisfaction and Job Design

- 10. Radiation, Electrostatic Fields and Alleged Health Hazards

- 11. Recommendations for VDT Workstations

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ergonomics In Computerized Offices by E. Grandjean in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.