![]()

Chapter 1. Introduction

Our discussion of peer-to-peer (P2P) concepts starts with an overview of the key applications and their emergence as mainstream services for millions of users. The chapter then examines the relationship of P2P with the Internet and its distinctive features compared to other service architectures. A review of P2P economics, business models, social impact, and related technology trends concludes the chapter.

P2P Emerges as a Mainstream Application

The Rise of P2P File-Sharing Applications

Nearly 10 years after the World Wide Web became available for use on the Internet, decentralized peer-to-peer file-sharing applications supplanted the server-based Napster application, which had popularized the concept of file sharing. Napster's centralized directories were its Achilles' heel because, as it was argued in court, Napster had the means, through its servers, to detect and prevent registration of copyrighted content in its service, but it failed to do so. Napster was subsequently found liable for copyright infringement, dealing a lethal blow to its business model.

As Napster was consumed in legal challenges, second-generation protocols such as Gnutella, FastTrack, and BitTorrent adopted a peer-to-peer architecture in which there is no central directory and all file searches and transfers are distributed among the corresponding peers. Other systems such as FreeNet also incorporated mechanisms for client anonymity, including routing requests indirectly through other clients and encrypting messages between peers. Meanwhile, the top labels in the music industry, which have had arguably the most serious revenue loss due to the emergence of file sharing, have continued to pursue legal challenges to these systems and their users.

Regardless of the outcome of these court cases, the social perception of the acceptability and benefits of content distribution through P2P applications has been irrevocably altered. In the music industry prior to P2P file sharing, audio CDs were the dominant distribution mechanism. Web portals for online music were limited in terms of the size of their catalogs, and downloads were expensive. Although P2P file sharing became widely equated with content piracy, it also showed that consumers were ready to replace the CD distribution model with an online experience if it could provide a large portfolio of titles and artists and if it included features such as a search, previews, transfer to CD and personal music players, and individual track purchase. As portals such as iTunes emerged with these properties, a tremendous growth in the online music business resulted.

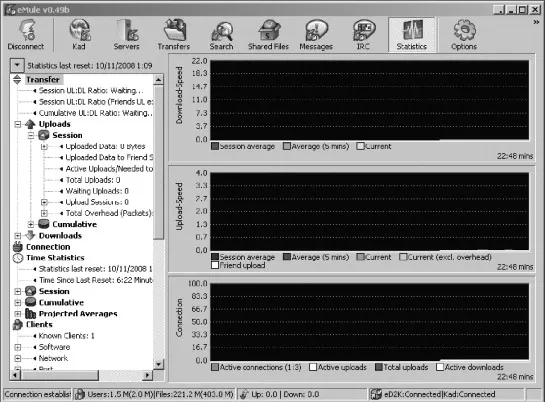

In a typical P2P file-sharing application, a user has digital media files he or she wants to share with others. These files are registered by the user using the local application according to properties such as title, artist, date, and format. Later, other users anywhere on the Internet can search for these media files by providing a query in terms of some combination of the same attributes. As we discuss in detail in later chapters, the query is sent to other online peers in the network. A peer that has local media files matching the query will return information on how to retrieve the files. It may also forward the query to other peers. Users may receive multiple successful responses to their query and can then select the files they want to retrieve. The files are then downloaded from the remote peer to the local machine. Examples of file-sharing client user interfaces are shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

Figure 1.1. LimeWire client.

Figure 1.2. eMule client search interface.

Despite their popularity, P2P file-sharing systems have been plagued by several problems for users. First, some of the providers of leading P2P applications earn revenue from third parties by embedding spyware and malware into the applications. Users then find their computers infected with such software immediately after installing the P2P application. Second, a large amount of polluted or corrupted content has been published in file-sharing systems, and it is difficult for a user to distinguish such content from the original digital content they seek. It is generally felt that pollution attacks on file-sharing systems are intended to discourage the distribution of copyrighted material. A user downloading a polluted music file might find, for example, noise, gaps, and abbreviated content.

A third type of problem affecting the usability of P2P file-sharing applications is the free-rider problem. A free rider is a peer that uses the file-sharing application to access content from others but does not contribute content to the same degree to the community of peers. Various techniques for addressing the free-rider problem by offering incentives or monitoring use are discussed later in the book. A related issue is that of peer churn. A peer's content can only be accessed by other peers if that peer is online. When a peer goes offline, it takes time for other peers to be alerted to the change in status. Meanwhile, content queries may go unanswered and time out.

The leading P2P file-sharing systems have not adopted mechanisms to protect licensed content or collect payment for transfers on behalf of copyright owners. Several ventures seek to legitimize P2P file sharing for licensed content by incorporating techniques for digital rights management (DRM) and superdistribution into P2P distribution architectures. In such systems, content is encrypted, and though it can be freely distributed, a user must separately purchase an encrypted license file to render the media. Through the use of digital signatures, such license files are not easily transferred to other users. See this book's Website for links to current P2P file-sharing proposals for DRM-based approaches.

Other ventures such as QTrax, SpiralFrog, and TurnItUp are proposing an ad-based model for free music distribution. The user can freely download the music file, which in some models is protected with DRM, but must listen to or watch an ad during download or playback. In these schemes, the advertiser instead of the user is paying the content licensing costs. Questions remain about this model, such as whether it will undercut existing music download business models and whether the advertising revenue is sufficient to match the licensing revenue from existing music download sites.

Voice over P2P (VoP2P)

Desktop VoIP (voice over IP) clients began to appear in the mid-1990s and offered free desktop-to-desktop voice and video calls. These applications, though economically attractive and technically innovative, didn't attract a large following due to factors such as lack of voice quality and limited availability of broadband access in the consumer market. In addition, the initially small size of the network community limited the potential of such applications to supplant conventional telephony. This continues to be a practical issue facing new types of P2P applications—how to create a community of users that can reach the critical mass needed to provide the value proposition that comes with scale.

Starting in 1996 with the launch of ICQ, a number of instant-message and presence (IMP) applications became widely popular. The leading IMP systems, such as AIM, Microsoft Messenger, Yahoo! Messenger, and Jabber, all use client/server architectures.6 Although several of these systems have subsequently included telephony capabilities, their telephony features have not drawn a large user community.

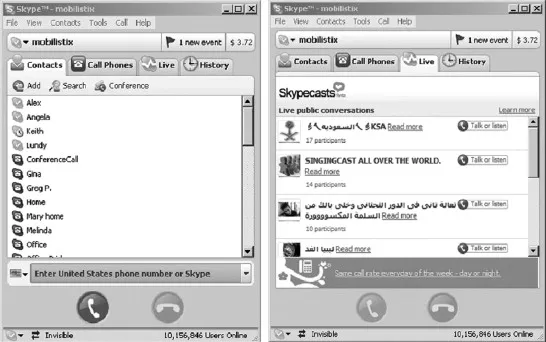

Skype is a VoP2P client launched in 2003 that has reached more than 10 million concurrent users. The VoP2P technology of Skype is discussed in Chapter 11. Compared to earlier VoIP clients, Skype offers both free desktop-to-desktop calls and low-cost desktop-to-public switched telephone network (PSTN) calls, including international calls. The call quality is high, generally attributed to the audio codec Skype uses and today's wide use of broadband access networks to reach the Internet. In addition, Skype includes features from IMP applications, including buddy lists, instant messaging, and presence. Unlike the file-sharing systems, Skype promises a no spyware policy.

The Skype user interface is shown in Figure 1.3. It includes a buddy list that shows other buddies and their online status. The user can select buddies to initiate free chat, voice, and group conference sessions. The user can also enter PSTN numbers to call, and these calls are charged.

Figure 1.3. Skype client.

P2PTV

The success of P2P file sharing and VoP2P motivated use of P2P for streaming video applications. P2PTV delivery often follows a channel organization in which content is organized and accessed according to a directory of programs and movies. Unlike file-sharing systems in which a media file is first downloaded to the user's computer and then played locally, video-streaming applications must provide a real-time stream transfer rate to each peer that equals the video playback rate. Thus if a media stream is encoded at 1.5 Mbps and there is a single peer acting as the source for the stream, the path from the source peer to the playback peer must provide a data transfer rate of 1.5 Mbps on average. Some variation in the playback rate along the path can be accommodated by prebuffering a sufficient number of video frames. Then if the transfer rate temporarily drops, the extra content in the buffer is used to prevent dropouts at the rendering side.

An attractive feature of peer-to-peer architectures for delivery of video streams is their self-scaling property. Each additional peer added to the P2P system adds additional capacity to the overall resources. Even powerful server farms are limited to the maximum number of simultaneous video streams that they can deliver. In a P2P network, any peer receiving a vi...