Maria R. Kosseva

1 Introduction

The European Union (EU) 6th Environmental Action Programme (6th EAP)1 provides the framework for environmental policymaking in the EU for the period 2002 to 2012 and outlines actions that need to be taken to achieve them. It identifies four environmental issues: climate change; nature and biodiversity; environment and health; and natural resources and waste. These are the priority issues of current European strategic policies. The 6th EAP also promotes the full integration and provides the environmental component of the community’s strategy for sustainable development.

The analyses below indicate that today’s understanding and perception of environmental challenges are changing—no longer can they be seen as independent, simple, and specific issues. The challenges are increasingly broad ranging and complex, part of a web of linked and interdependent functions provided by different natural and social systems. This implies an increased degree of complexity in the way we understand and respond to environmental challenges (European Environmental Agency [EEA], 2010).

In parallel, existing European environmental policies present a robust basis on which to build new approaches that balance economic, social, and environmental considerations. Future actions can draw on a set of key principles that have been established at the European level: the integration of environmental considerations into other measures; precaution and prevention; rectification of damage at source; and the polluter-pays principle. Waste policies can essentially reduce three types of environmental pressures: emissions from waste treatment installations such as methane from landfill; impacts from primary raw material extraction; and air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from energy use in production processes. The use of resources, water, energy, and the generation of waste are all driven by our patterns of consumption and production. Eating, drinking, and mobility are the areas of household consumption with the highest pressure intensities and the largest environmental impact. European policy has only recently begun to address the challenge of the growing use of resources and unsustainable consumption patterns. European policies such as the Integrated Product Policy and Directive on Eco-design focused on reducing the environmental impacts of products, including their energy consumption, throughout their entire life-cycle. It is estimated that over 80% of all product-related environmental impacts are determined during the design phase of a product (EEA, 2010).

In this chapter, food wastes generated along the food supply chain are defined, and various legal aspects of this waste are presented. Best Available Technique candidates for the food and drink sector are evaluated as a reference point in the environmental permit regulation for industrial installations in EU Member States. This method is used to implement the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) Directive (96/61/EC). Other EU documents, which we address here, are the Packaging Waste Directive (1994), the Animal By-products Directive (2000), and the Waste Framework Directive (2008).

1.1 Definitions of Food Industry Waste (FIW)

Different definitions of food waste with respect to the complexities of food supply chains (FSCs) exist. Food waste occurs at different points in the FSC, although it is most readily defined at the retail and consumer stages, where outputs of the agricultural system are self-evidently food for human consumption. In contrast to most other commodity flows, food is biological material subject to degradation, and different foodstuffs have different nutritional values. Below are five definitions referred to herein:

1. Wholesome edible material intended for human consumption, arising at any point in the FSC that is instead discarded, lost, degraded, or consumed by pests (FAO, 1981).

2. As (1), but including edible material that is intentionally fed to animals or is a by-product of food processing diverted away from the human food (Stuart, 2009).

3. Waste is “any substance or object the holder discards, intends to discard or is required to discard”. “Products whose date for appropriate use has expired” targets food waste, with “date” referring to the expiry date of a food. This definition is from the EU Council Directive Waste 75/442/EEC [91/156/EEC] (EU, 1991a, b). Clearly any produce that does end up in landfill is a waste and can be quantified accordingly by the tonnage. But quantifying waste in farm-to-retailer supply chains is more difficult because rejection does not necessarily trigger disposal, but redirection to other markets.

4. “Uneaten food and food preparation wastes from residences and commercial establishments such as grocery stores, restaurants, and produce stands, institutional cafeterias and kitchens, and industrial sources like employee lunchrooms” as defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (2006).

5. Food or drink products that are disposed of (includes all waste disposal and treatment methods) by manufacturers, packers/fillers, distributors, retailers and consumers as a result of being damaged, reaching their end-of-life, are off cuts, or deformed (outgraded) (WRAP, 2010).

1.2 Waste Streams Considered in This Book

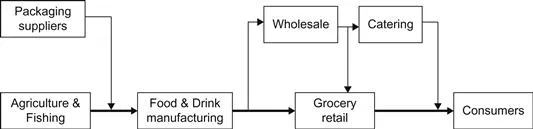

Within the literature, food waste postharvest is likely to be referred to as “food losses” and “spoilage”. Food loss refers to a decrease in food quantity or quality, which makes it unfit for human consumption (Grolleaud, 2002). At later stages of the FSC, the term food waste is applied and generally relates to behavioral issues. Food losses/spoilage, conversely, relate to systems that require investment in infrastructure. In this work, we refer to both food losses and food waste generated along the food and drink supply chain (Figure 1.1) as food industry waste, considering the first two definitions to be most relevant. The method of measuring the quantity of food waste is usually by weight, although other units of measure include calorific value, quantification of greenhouse gas impacts, and lost inputs (e.g., nutrients and water).

Figure 1.1 The food and drink supply chain. Adapted from Mena et al. (2010).

2 Various Legal Aspects of Food Waste

Legislation has been used around the world to prevent, reduce, and manage waste (e.g., promoting recycling and energy recovery). In the EU, the Council Directive on Waste (1991), originally introduced in 1975 and revised in 1991, deals with the regulatory framework for the implementation of the European Commission’s Waste Management Strategy of 1989. It covers waste avoidance, disposal, and management. The EU Council directive on Hazardous Waste (1991) was introduced to align management of these materials across Member States (MS). Other documents related to food waste include the EU Council Directives on Packaging Waste (1994), Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (1996), Landfill of Waste (1999), and Animal By-products (2000).

EU Directive 94/62/EC aimed to harmonize national measures concerning the management of packaging and packaging waste in order to prevent any impact thereof on the environment of all MS as well as of third countries or to reduce such impact. MS may encourage a system of reuse of packaging in an environmentally sound manner. Moreover, they should encourage the use of materials obtained from recycled packaging waste for the manufacture of packaging and other products (Arvanitoyannis, 2008).

The EU Council Directive on Animal By-products (2000) categorizes waste into three sections:

• Category 1: High risk, to be incinerated;

• Category 2: Materials unfit for human consumption; most types of this material must be incinerated or rendered;

• Category 3: Material which is fit for but not destined for human consumption.

The UK has its own order for animal by-products introduced in 1999 and amended in 2001 and again in 2003 (Statutory Instrument 2003 No. 1484) (OPSI, 2003), which aims to minimize disease transmission such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). The current legislation requires the prevention of feeding livestock with catering waste that has been in contact with animal carcasses or material presenting similar hazards.

2.1 Selecting Best Available Technique Candidates for the Food and Drink Sector

Best Available Techniques (BATs) are an important reference point in the environmental permit regulation for industrial installations in the EU MS, which have to implement the IPPC. BATs correspond to the techniques and organizational measures with the best overall environmental performance that can be introduced at a reasonable cost (Derden et al., 2002). Central to this approach are scores given on technical feasibility, on cross media environmental performances, and on economic feasibility. The approach was tested in the fruit and vegetable processing industry. Their recommendation to map the sector from a technical and economic point of view, in order to understand its structure and financial capabilities, as well as to be able to assess sustainability of decisions taken, was adopted in a study by Midžić-Kurtagić et al. (2010).

Having in mind differences in the technological structure and the environmental priorities between countries, Schollenberger et al. (2008) propose a consistent and flexible assessment method for the evaluation of process improvements based on resource efficiency. They suggest that determination of candidate BATs requires the assessment of parameters from the three pillars of sustainability: economic, ecological, and social. Their logical application indicates that BAT candidate selection should be performed based on ecologic, economic, and social criteria. In this context, a concept of sustainable development can be understood as proposed by Strange and Baley (2008):

• A conceptual framework: a way of changing the predominant world view to one that is more holistic and balanced;

• A process: a way of applying the principles of integration, across space and time and to all decisions;

• A goal: identifying and solving specific problems of resource depletion, healthcare, social exclusion, poverty, etc.

Therefore, the selected method for assessing BAT sustainability should offer the criteria for analysis of relations between different issues and propose adequate solutions. Problems related to the overexploitation of resources, environment, and human health are interconnected from the point of view of cause and effect, and the solutions should ...