GEOGRAPHIC AND GEOMORPHOLOGIC SETTING

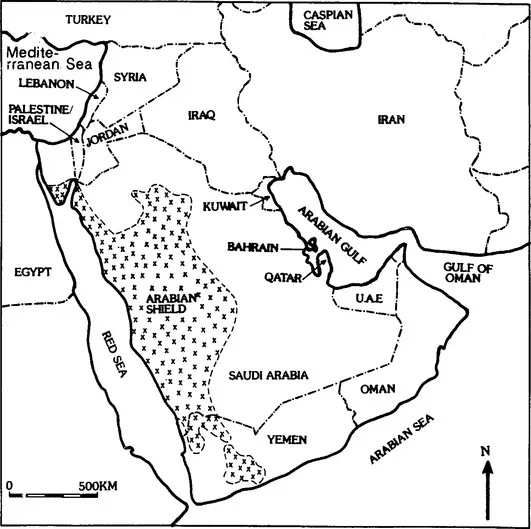

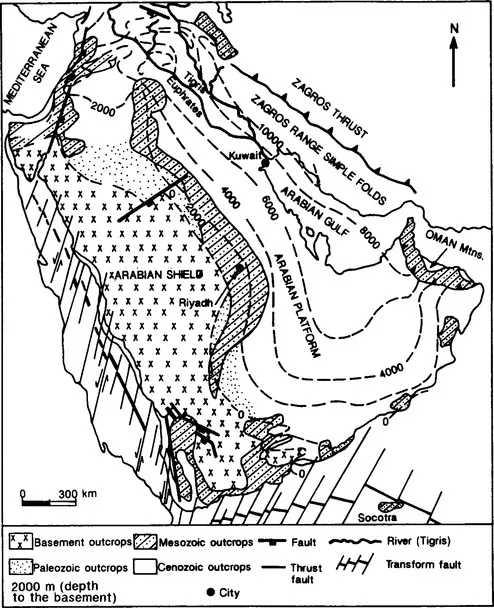

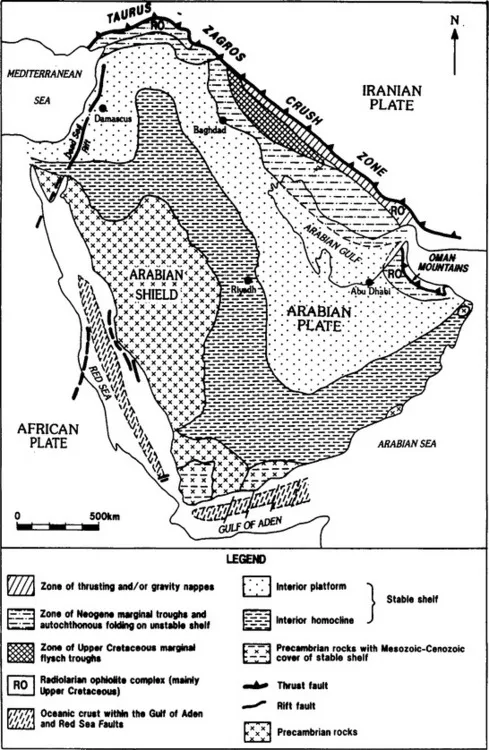

The countries of the Middle East (Fig. 1.1), the region reviewed in this book, cover parts of the lands of the eastern Mediterranean and the greater part of Arabia (Arabian Shield, Arabian Platform and Arabian Gulf), and the western Zagros Thrust Zone, an area enclosed between 13° and 38° N and 35° and 60° E (Figs. 1.2 and 1.3). Topographically, the higher elevations generally lie to the west in the Arabian Shield and pass eastward into the lower-lying areas occupied by the Arabian (Persian) Gulf and the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. To the east of these lie the Zagros ranges, with the Zagros Crush Zone forming the boundary of the region considered here, although as will appear in the following pages, it makes geological sense to include southwestern Iran in the early Phanerozoic. The Arabian Gulf is a shallowly submerged area, with an average depth of only 60 m (197 ft); even the deepest part, lying at the southeastern end, has a depth of only 240 m (787 ft). Bathymetric charts show a depth asymmetry, with the deeper parts lying closer to the Iranian than to the Arabian shore. At its northern end, the Arabian Gulf gradually is being filled by sediments forming the prograding Tigris-Euphrates Delta (Fig. 1.2). At the southeastern end of the Arabian Gulf, there is a sharp change in trend, and the gulf narrows, forming the Strait of Hormuz, where the Musandam Peninsula projects toward the Iranian shore. The submarine continuation of the Arabian Peninsula further restricts open contact of the gulf with the Arabian Sea. However, the greatest depths are found in the Straits. Beyond the Straits (Hormuz and Bab Al Mandab near the Gulf of Aden), a profound geological change occurs; while the Arabian Gulf lies on continental crust, the floor of the Gulf of Oman and Gulf of Aden is oceanic.

Fig. 1.1 General location map of the Middle East, indicating the states and major cities. Note that the state boundaries in all of the maps are not formal international boundaries.

Fig. 1.2 Major subdivisions of the Middle East. (from Dubertret and André,1969; Brown, 1972; Saint-Marc, 1978)

Fig. 1.3 Structural elements of the Middle East. (modified from Henson, 1951; and Beydoun, 1988)

The natural boundaries of the Middle East are most easily defined to the north and northeast, where the Taurus Mountains pass eastward to the Zagros Fold Belt (Figs. 1.1 and 1.3). North of the Taurus Mountains lies the Anatolian Plateau, which is bounded to its north by the Pontic Mountains. Topographically, these two ranges combine to the east, although the geological continuation of the Pontian Belt may be sought in the Caucasian province. In a similar manner, their eastward extension also divides to form the Zagros and Alborz Mountains, which together enclose the Iranian Plateau. Topographically, the Zagros is continued to the east by the Makran ranges. The Makran ranges are geologically very young and still in the process of formation; the geological continuation of the Zagros is formed by the mountains of Oman. The region is bounded by Owen Fracture Zone and Gulf of Aden rifting to the south and by the rift system of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba to the west.

The area enclosed within the boundaries of the region is more than 1,000,000 km2 and is sparsely populated, with the exception of the fertile crescent of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. It contains within its borders a major part of the world’s known hydrocarbon reserves and a disproportionate number of the supergiant and giant fields. It is the economic importance of these resources that has stimulated an interest in the area that has increased as the extent of the resources has become better established. The northern third of the region is covered by the alluvial deposits from the Tigris-Euphrates River System, which drains the area from the mountains to the north and east. Presently, the Tigris-Euphrates Delta is prograding and gradually filling the Arabian Gulf. The larger area to the south contains two of the world’s great deserts: the An Nefud (Nafud) in the north, and the Rub al Khali in the south. Within the Rub al Khali is a large sand sea, with dunes up to 200 m (656 ft) in height; in the Great Nefud, the sand dunes, which cover about 145,000 km2, are up to 300 m higher than the surrounding terrain. Farther north in the Syrian desert, ablation has removed most of the loose sand, thereby exposing extensive gravel- or rock-covered plains, and desert pavements, making crossing the desert difficult.

Geomorphology and climate (principally the availability of water) have controlled human settlement and communications in the Middle East. In western Saudi Arabia lies an old pediplane with inselbergs. Although its exact age is not known, it is overlain by early Tertiary lavas. Several erosion surfaces have been defined; the principal surfaces are those at 1,650 m (5,280 ft), 1,200 m (3,840 ft) and 900 m (2,880 ft), the last and youngest of which is known to predate rifting.

The whole region lies within the arid subtropical zone, and only a few, very restricted parts of Lebanon and Turkey are not classified as extremely arid. During the summer, the main track of the jet stream that controls the paths of atmospheric depressions passes north of the Pontic Mountains. During the winter, the track of the jet stream moves rapidly southward to cover the northern Arabian Gulf. Few depressions pass south of 30° N. Therefore, the area receives little benefit from the depressions during summer, except perhaps the Caspian shores of Iran, or winter; thus, it is not surprising that large areas have a rainfall regime of 100-300 mm/year. In general, the lower the precipitation, the greater its variability; and, in Bahrain, with an annual average rainfall of 76 mm, the range may be from as little as 10-170 mm. Only the Arabian Sea coast benefits to a limited extent from the passage of the monsoon. The location of settlements is, therefore, restricted to the areas of permanent springs and oases or areas where irrigation is possible. In the deserts, a few nomads eke out a precarious existence grazing livestock. Since prehistoric times, the principal population is to be found along the Tigris-Euphrates River System, and in Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) along the shores of the Arabian Gulf, where before the discovery of oil, pearl fishing and coastal transport provided subsistence for a small population. Despite the enormous wealth generated by oil revenues, future development will require some means to make the land more hospitable. The irrigation schemes in eastern Arabia have only a qualified success; and, as they depend upon groundwater, which has only limited possibilities for recharge, or upon fossil water, there is a definite limit to extensive development. Desalination plants in the coastal regions are an expensive means of providing water for other than human consumption.

The basic soil cover consists of red desert soil, which changes to sierozems, or gray desert soil in the southwest and northeast. In the north, reddish prairie soils develop, and within the neighboring mountains, chernozem or chestnut soils develop. The natural vegetation is characteristic of desert sand semi-deserts, with scrub woodlands at the higher elevations and steppe in the extreme north. Cultivation is restricted mainly to the flood plains. Along the low, flat and sandy shores, salt flats or sabkhas have formed in shallow depressions. Due to the high rates of evaporation, salt crusts develop that, when the salt is relatively free from sand, have been exploited locally. Under storm conditions, these low-lying areas may be flooded by the sea, which can extend miles inland. Under other conditions, aeolian dunes may bury the sabkhas.

Agriculture is still important in the economies of many of the countries in the region, not only providing food and export revenue, but a source of employment. For environmental and technological reasons, crop yields generally are low, and crop variety is restricted. Oil revenues have meant that a progressively larger percentage of the food requirements are met by imports as well as fueling economic development.

Politically, the area contains a number of large countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Oman, most of them sparsely populated; and a number of small states bordering the Arabian Gulf, such as the U.A.E., Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait. In southern Arabia lies the Republic of Yemen; in the Levant are the smaller states of Israel/Palestine and Lebanon.

The economy of the greater part of the region is dominated by petroleum, not only in terms of current production, but also in terms of potential. The first commercial oil was discovered in the Middle East region in Iran in 1908. Subsequently, commercial oil was discovered in Iraq in 1927, in Bahrain in 1932, in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in 1938, in Qatar in 1939, in Turkey in 1951, in the Divided Zone in 1953, in Syria in 1956, in the U.A.E. in 1958, in Oman in 1962, in Yemen in 1984 and in Jordan in 1985. Many of the Middle East countries have non-associated natural gas accumulations, as well as considerable volumes of associated gas. The development of the hydrocarbon resources has led not only to the exportation of crude oil and gas, but also to the development of significant refining and petrochemical capacities. Both economic and political factors have led to the development of an extensive network of pipelines (Fig. 1.4). Other primary minerals exist; but, on the whole, these are poorly known, and even less exploited. Only the chromium and antimony in Turkey is of significance in world trade. There are, however, important phosphate deposits in Jordan and Israel/Palestine, and Saudi Arabia. The Arabian Shield has good potential deposits of copper, gold, iron, silver, manganese and lead. Yemen has a fair potential in copper, iron and salt. In Oman, occurrences of copper, chromite, asbesto...