1.1 Geological Questions

The Korean Peninsula consists of scenic mountains and valleys that run one after another (Figures 1.1–1.3). These features have descended from crustal deformation and the associated plutonic and volcanic activities. Rivers run through the valleys, carrying sediments mostly toward the west and the south, forming floodplains. Where the rivers meet the coastal plain, estuaries form. Along the western and southern coasts of the peninsula, tidal flats are extensive, rivaling those of the North Sea and the Bay of Fundy. The Yellow Sea is a shallow (55 m on average) epicontinental sea, surrounded by the landmass of China and Korea. Off the western and southern coasts of the peninsula, there are more than 3000 islands. However, the eastern continental shelf is narrow and transitional to a bowl-shaped deep basin, the Ulleung Basin, and the Korea Plateau, which are dotted by numerous volcanic seamounts and islands, including the Ulleung and Dok islands (Figure 1.4). The volcanic island of Jeju comprises a central crater, about 360 scoria cones, and tuff rings and cones.

Figure 1.1 Satellite image of the Korean Peninsula. The peninsula consists largely of mountains (about 65%). There are about 3000 islands off the south and west coasts. Source: GOCI/COMS RGB Color Composite Image processed by Korea Ocean Satellite Center/Korea Ocean Research and Development Institute.

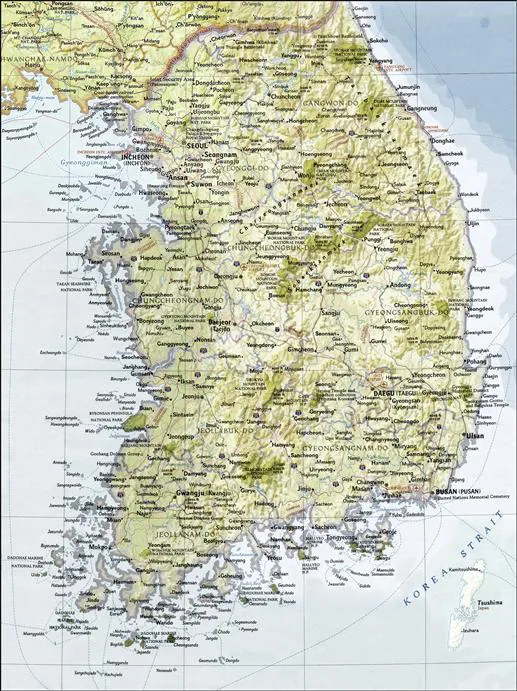

Figure 1.2 Geographic map of South Korea. Source: National Geographic (2003) by permission of the National Geographic Society.

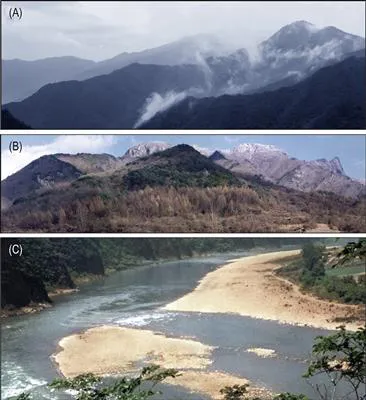

Figure 1.3 (A) View of a mountain chain in the southeast of Taebaek city, Gangwon Province. The ridges comprise sedimentary rocks (limestone and sandstone) that formed in shallow water environments during the Paleozoic (about 520–250 Ma) and deformed in the Mesozoic (ca. 250–150 Ma). The mountains represent remnant of continuous denudation for the last 150 million years. (B) Snow covered Wolak mountain in the background. It consists of granite intruded into metasedimentary rocks. (C) The meandering East River showing mid-channel and sidebars of gravelly sands.

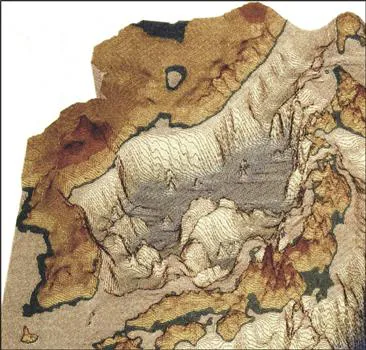

Figure 1.4 Topographic relief of the Korean Peninsula and the northeast Asian margin. Source: Courtesy of K. Tamaki.

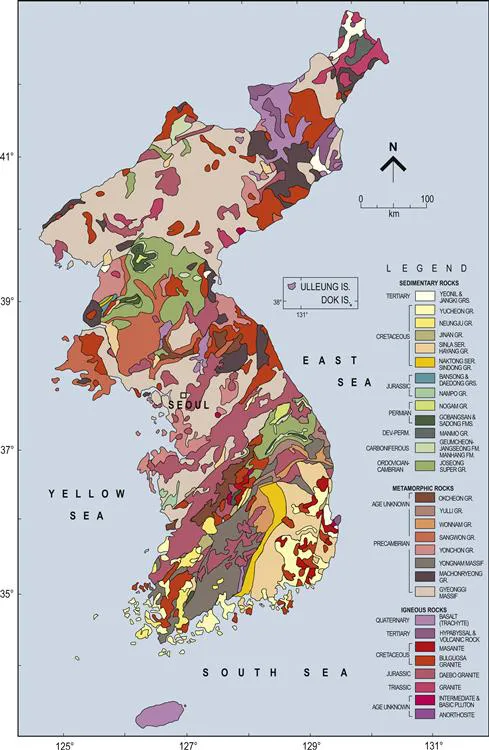

The Korean Peninsula comprises denudation remnant of deformed basement rocks and sedimentary successions, concealing a long history of crustal deformation (Figure 1.5). Sedimentary rocks especially contain records of environmental change through Earth’s history, including climate change, the rise and fall of sea level, and the movement of tectonic plates over millions of years. The peninsula presents a number of fundamental questions as to its origin and dynamic processes. What constitutes the scenic mountains and ridges? When and how did these mountain chains form? Was it due to the collision of the tectonic plates? How often was the continent submerged under the sea throughout Earth’s history? How are the rocks in the peninsula linked to those of China and Japan? What are the origins of the deep basins and submarine plateaus in the East Sea? How did the continent under the Yellow Sea form and evolve? How would the coastal areas be affected by sea-level change over timescales of a few decades to centuries? These are commonly asked questions regarding dynamic processes and environmental changes of the Korean Peninsula on land and under the sea.

Figure 1.5 Geologic map of the Korean Peninsula. Source: Korea Institute of Energy and Resources (1981) by permission of the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources.

1.2 Sedimentary Facies Analysis

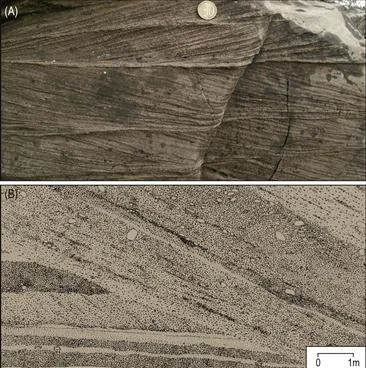

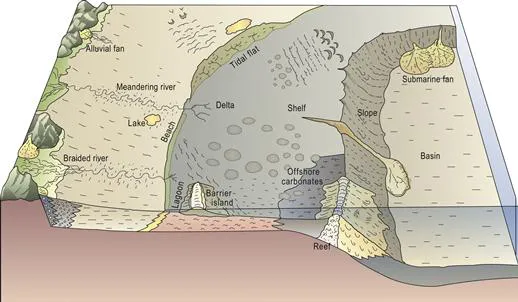

Sedimentary rocks are important constituents (more than 50%) of the crust of the Korean Peninsula. Sedimentary rocks (and sediments) are characterized by grain size and sedimentary structures, i.e., sedimentary facies, defined as a depositional unit characterized by a particular combination of grain size (lithology) and sedimentary (physical and biological) structures (Figure 1.6). Each unit of sedimentary facies represents distinct depositional processes that act on the sediments in particular environments (Figure 1.7). Genetically related facies can form a group, defined as a facies association or a sequence that has some environmental significance. An analysis of sedimentary facies thus leads the way to diagnosing depositional processes and environments (Dalrymple, 2010).

Figure 1.6 Sedimentary facies. (A) Bidirectional cross-bedded sandstone, Mantou Formation, Shandong Province, China. (B) Line drawing of large-scale scour at the base of foreset. The lower left part is characterized by cross stratified, disorganized, and openwork amalgamated beds of conglomerates similar to Gilbert-type topset facies. The foreset is characterized by steeply inclined beds of stratified and inversely graded conglomerates, Doumsan Fan Delta, Pohang Basin.

Figure 1.7 A large-scale view of depositional environments on Earth’s surface.

Sedimentary facies analysis is essential to the study of stratigraphy, which is primarily concerned with the recognition of distinct bodies of rocks in a chronological framework. A lithostratigraphic unit is defined by its lithologic characteristics in stratigraphic position relative to other bodies of sedimentary rock. A sedimentary rock unit can also be characterized by its fossil contents, biostratigraphy. Various other methods have also been used to define stratigraphic units, including magnetostratigraphy and chemostratigraphy.

Sedimentary facies analysis leads to an understanding of controls on basin evolution, including tectonics, climate changes, and sea-level changes (Miall, 2000, 2010). Plate movement causes subsidence of the crust, which provides the space for the accumulation of sediments. Sedimentary basins are commonly formed according to the plate tectonic regime: divergent, convergent, transcurrent, intraplate, and hybrid settings. Subsidence is induced by a thinning of the crust due to stretching, erosion, and magmatic withdrawal as well as tectonic and sedimentary loading and others (Busby and Azor, 2011). Uplift/subsidence also affects climate changes and the amounts of sediment supply. Along with these factors, sea-level changes control depositional processes and environments, especially in the shoreline and shallow waters.

Sedimentary facies analysis eventually leads to sequence stratigraphy, which is the study of rock relationships within a chronostratigraphic framework of repetitive, genetically related strata bounded by surfaces of erosion or nondeposition, or their correlative conformities (Posamentier et al., 1988; Van Wagoner et al., 1990). Sequence stratigraphic analysis focuses on the geometric characters of stratal patterns and identifications of key surfaces to determine the chronological order of basin fills (Catuneanu, 2006; Emery and Myers, 1996). The underlying tenet of sequence stratigraphy was that a change in sea level would result in a change in stratal patterns, which could be compared among basins worldwide. This deductive generic view of sequence stratigraphy has hampered, however, to further process-based sedimentological approach to an integrated basin analysis. The high variability of bounding surfaces and stratigraphic units requires inductive analysis for individual rock records (Catuneanu et al., 2009, 2010). Modern sequence stratigraphy focuses on the changes in stratal stacking patterns in response to varying accommodation and sediment supply through time (Catuneanu et al., 2010; Miall, 2010). Attention is now given to the specifics of how stratal architecture can throw light on depositional processes and allogenic controls.

Over the past 30 years, extensive sedimentary facies analyses have been made in major sedimentary basins of the Korean Peninsula, including the siliciclastics, carbonates, and mixed siliciclastic–carbonate successions as well as the nonmarine deposits. The results have led to significant advancement in the understanding of depositional processes and environments as well as of dynamic crustal evolution of the peninsula on land and under...