eBook - ePub

Ethics and Professionalism in Forensic Anthropology

This is a test

- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ethics and Professionalism in Forensic Anthropology

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Forensic anthropologists are confronted with ethical issues as part of their education, research, teaching, professional development, and casework. Despite the many ethical challenges that may impact forensic anthropologists, discourse and training in ethics are limited. The goal for Ethics and Professionalism in Forensic Anthropology is to outline the current state of ethics within the field and to start a discussion about the ethics, professionalism, and legal concerns associated with the practice of forensic anthropology.

This volume addresses:

- The need for professional ethics

- Current ethical guidelines applicable to forensic anthropologists and their means of enforcement

- Different approaches to professionalism within the context of forensic anthropology, including issues of scientific integrity, qualifications, accreditation and quality assurance

- The use of human subjects and human remains in forensic anthropology research

- Ethical and legal issues surrounding forensic anthropological casework, including: analytical notes, case reports, peer review, incidental findings, and testimony

- Harassment and discrimination in science, anthropology, and forensic anthropology

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ethics and Professionalism in Forensic Anthropology by Nicholas V. Passalacqua,Marin A. Pilloud in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Diritto & Scienza forense. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DirittoSubtopic

Scienza forenseChapter 1

Introduction to Professionalism, Ethics, and Forensic Anthropology

Abstract

Forensic anthropology is still a young discipline, just beginning to develop its own standards and best practices, and define itself as a profession. This chapter introduces the volume, including a short introduction to professionalism, ethics, and science, and briefly summarizes the volume’s contents.

Keywords

Forensic anthropology; science ethics; morals; professionalism; practice; ethical code

While considered an important aspect of education in medical school, professionalism and ethics are not subjects frequently discussed in forensic anthropology classrooms. Applied anthropology programs are more likely to offer ethics as part of their education; however, ethics are not frequently found as a required part of anthropology programs (Trotter, 2009). This general trend is also reflected in the literature as there are few publications that deal with professionalism or ethics within the context of forensic anthropology (see France, 2012; Walsh-Haney and Lieberman, 2005).

This lack of focus on ethics does not mean that forensic anthropologists are unethical. Rather the lack of material on these subjects likely results from the relatively young nature of forensic anthropology and the fact that even now much of forensic anthropology is rather disjointed and lacks professional standards. While there are numerous ethical codes to which many forensic anthropologists adhere as part of their professional memberships (e.g., those of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences [AAFS], the American Association of Physical Anthropologists [AAPA], the American Board of Forensic Anthropology [ABFA])1, there are also many individuals practicing forensic anthropology, or using the title “forensic anthropologist” without qualifications or any of these professional affiliations.

The goal for this volume echoes that of a similar volume, Ethics and the Profession of Anthropology (Fluehr-Lobban, 2003:xiii), in that we aim to begin the “dialogue for ethically conscious practice” of forensic anthropology. We will discuss current and best practices on a number of topics, and outline the need for professional and ethical standards within the field. The discussion we present is meant to be beyond any specific set of state or federal regulations that may guide different types of analyses, testing, reporting, or handling of remains. Instead, we explore the role of the forensic anthropologist and the ethical boundaries of working with human remains within the medicolegal system. While we discuss current and best practices on a number of topics, we do not intend for this volume to be an exhaustive reference of proper conduct in all circumstances, nor do we anticipate all forensic anthropologists to agree with the issues presented here. Additionally, we will not discuss the history of ethics in anthropology generally, nor touch on anthropological issues outside of those directly relating to forensic anthropology. Rather, we hope this volume will start the discussion about the ethical practice of forensic anthropology and bring to light different approaches to professionalism and the practice of forensic anthropology.

Introduction to Professionalism

In very general terms, a profession is a paid occupation, a professional is someone who belongs to a certain profession, and professionalism is conduct associated with a particular profession. All of these definitions fail to address what constitutes the qualifications and appropriate behaviors that are requisite for a given profession. What constitutes professionalism can be defined according to various disciplines. Within forensic anthropology, and the forensic sciences in general, there is a dearth of literature on the definition of these terms. Perhaps the most relevant to forensic anthropology would also be that outlined for medical professionals. Generally, within this literature a professional is someone who possesses a body of special knowledge, practices within an ethical framework, and fulfills a societal need (Pellegrino, 2002). Within the context of forensic anthropology, we can extend this to include a professional as someone who is a properly trained subject-matter expert who will analyze a case without a conflict of interest, and will follow an appropriate code of conduct. Throughout this book we outline more specific definitions of professionalism (Chapter 2: The Need for Professional Ethics) and the specific practices and behaviors that are requisite of a professional forensic anthropologist (Chapter 4: Defining the Role of the Forensic Anthropologist; Chapter 5: The use of Human Subjects in Forensic Anthropology Research; Chapter 6: Reporting and Testifying in Forensic Anthropology; and Chapter 7: Discrimination and Harassment in Forensic Anthropology).

Introduction to Ethics

Ethics is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with morality and behaviors (i.e., conduct) that can be considered right or wrong based on different criteria (Bowen, 2009). There are traditionally three fields of inquiry within the field of ethics: metaethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics (Attfield, 2012). Within this treatment, we will focus on normative ethics, to establish standards and guidelines for behavior within forensic anthropology. Here we define ethics as guidelines for the behavior of individuals within a specific profession or discipline. An ethical code is a set of rules dealing with ethical issues that have been agreed upon by a professional body (e.g., the AAFS). Different professional organizations may have different ethical codes, but all are used in order to ensure members avoid unprofessional behaviors and thus maintain the credibility of the profession and professional organization.

Morals and moral codes are similar to ethics and ethical codes; however, they vary in a few key ways. Most importantly, morals are not professionalized; meaning they are not typically written down or agreed upon by all parties. Further, because morals are not professionally recognized, they often lead to disagreement about their validity or applicability as each individual may have their own personal interpretation regarding a moral rule. Of note is that all “ethical codes draw to some extent on the generally accepted moral values of the culture in which the ethical codes are developed; but moral principles are, in themselves, insufficient to govern action” (Barnett, 2001:14). While Chapter 3, Current Ethical Guidelines and a Theory of Ethics, will deal specifically with different ethical codes relating to forensic anthropology, it is important to remember that each profession may have its own ethical codes, which function uniquely in order to promote positive impacts from its practitioners on society.

Introduction to Forensic Anthropology

Forensic anthropology is “the application of anthropological method and theory to matters of legal concern, particularly those that relate to the recovery and analysis of the human skeleton” (Christensen et al., 2014:2). For this volume we will take the typical North American approach to forensic anthropology, that is combining the systematic search and recovery of evidence and remains (forensic archaeology) and the analysis of biological, usually dental and skeletal materials (forensic anthropology) into the singular discipline of forensic anthropology. However, we do acknowledge that different regions have different approaches to the practice of forensic anthropology. In the United Kingdom for example, forensic archaeology is considered a separate discipline, and training in forensic archaeology typically occurs as an entirely detached program from forensic anthropological (i.e., skeletal) training. Further, in much of Europe, analyses typically considered to fall under the purview of forensic anthropology are performed by doctors of forensic medicine, and forensic archaeology is performed by individuals trained in archaeology. While we plan to focus on the North American approach to forensic anthropology, when relevant, we will touch on various international models as well.

Forensic anthropology, like all forensic sciences, can be thought of as employing rigorous scientific methodology combined with forensic (meaning legal) documentary paperwork (largely for the purposes of traceability and transparency). Functionally, what this means is that despite what television shows lead us to believe, forensic anthropology, or any forensic science, is actually a tedious endeavor requiring significant amounts of paperwork, documentation, and bureaucracy for even simple analyses and reporting.

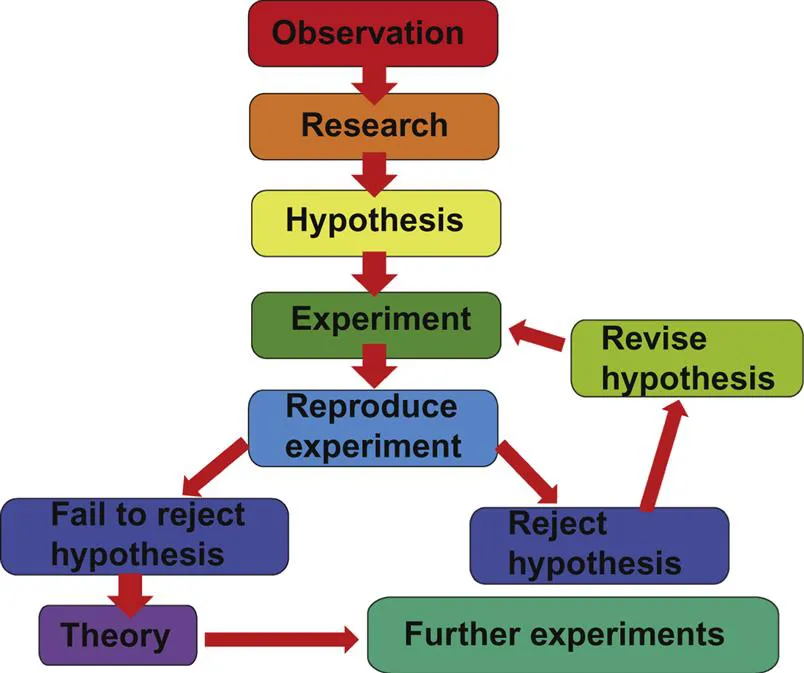

When it comes to any of the forensic sciences the importance of the scientific method cannot be discounted. The scientific method requires that scientists observe different phenomena using valid methods, and to use the results of these observations to draw conclusions about what was observed. “Critical to the scientific method is that the scientist’s conclusions can be verified by other scientists. This requires that the methods and processes that underlie a scientist’s opinion are available to another scientist for review” (Barnett, 2001:18). Further, science must follow the scientific method as illustrated in Fig. 1.1. As the reader is well aware, this process begins with an observation that is followed by topical research that helps in the development of a testable statement, i.e., a hypothesis. The hypothesis leads to the formulation of a research experiment in which the hypothesis can be falsified. If the hypothesis can be falsified the researcher rejects it and formulates a separate testable hypothesis to begin the process again. If repeated experiments fail to falsify a hypothesis the beginnings of a theory may be formulated that will be subjected to multiple additional experiments. This approach is in line with the Popper view on science and falsification (Popper, 1963), which is most applicable to the forensic sciences.

Outline of the Volume

This book is meant to be a brief introduction to professionalism, ethics, and their relevance to the practice of forensic anthropology. As such, we discuss: the need for professional ethics (Chapter 2: The Need for Professional Ethics); currently available ethical guidelines and their means of enforcement (Chapter 3: Current Ethical Guidelines and a Theory of Ethics); the role of the forensic anthropologist in death investigations (Chapter 4: Defining the Role of the Forensic Anthropologist); the use of human remains and human subjects within the context of forensic anthropology (Chapter 5: The use of Human Subjects in Forensic Anthropology Research); analysis, reporting, and testifying (Chapter 6: Reporting and Testifying in Forensic Anthropology); and harassment and discrimination (Chapter 7: Discrimination and Harassment in Forensic Anthropology); with a short summary and concluding remarks (Chapter 8: Looking Backward and Thinking Forward). Finally, as reference material, we have also included a number of appendices.

Forensic anthropology is still a young discipline, just beginning to develop its own standards, define itself as a profession, and to develop best practices. As previously highlighted, it is our hope that the information presented here will serve as a reference for ongoing discussions about the future of the discipline. As forensic anthropology grows and moves forward it will be critical to have a clear outline of professional and ethical practice and behavior, as it is these characteristics that give a discipline authority and support expertise.

Chapter 2

The Need for Professional Ethics

Abstract

This chapter discusses the need for professional ethics, focusing on issues related to scientific integrity, the maintenance of transparency, and the need to avoid misconduct and conflicts of interest. In addition, the 2009 National Academy of Sciences...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- Chapter 1. Introduction to Professionalism, Ethics, and Forensic Anthropology

- Chapter 2. The Need for Professional Ethics

- Chapter 3. Current Ethical Guidelines and a Theory of Ethics

- Chapter 4. Defining the Role of the Forensic Anthropologist

- Chapter 5. The Use of Human Subjects in Forensic Anthropology Research

- Chapter 6. Reporting and Testifying in Forensic Anthropology

- Chapter 7. Discrimination and Harassment in Forensic Anthropology

- Chapter 8. Looking Backward and Thinking Forward

- Appendix A. Acronyms

- Appendix B. SWGAnth Guidelines

- Appendix C. Websites of Ethical Codes (Accessed November 2017)

- References

- Index