eBook - ePub

Selecting and Implementing an Integrated Library System

The Most Important Decision You Will Ever Make

- 126 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Selecting and Implementing an Integrated Library System

The Most Important Decision You Will Ever Make

About this book

Selecting and Implementing an Integrated Library System: The Most Important Decision You Will Ever Make focuses on the intersection of technology and management in the library information world. As information professionals, many librarians will be involved in automation projects and the management of technological changes that are necessary to best meet patron and organizational needs.

As professionals, they will need to develop numerous skills, both technological and managerial, to successfully meet these challenges. This book provides a foundation for this skillset that will develop and acquaint the reader with a broad understanding of the issues involved in library technology systems.

Although a major topic of the book is integrated library systems (a fundamental cornerstone of most library technology), the book also explores new library technologies (such as open source systems) that are an increasingly important component in the library technology world. Users will find a resource that is geared to the thinking and planning processes for library technology that emphasizes the development of good project management skills.

- Embraces both technology and management issues as co-equals in successful library migration projects

- Based on the experiences of a 20+ year career in libraries, including three major automation project migrations

- Includes increasingly relevant subject matter as libraries continue to cope with shrinking budgets and expanding library demands for services

- Contains the direct experiences of the University of Washington system in the Orbis-Cascade Alliance project, a project uniting 37 libraries across two states that combined both technical and public service functions

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Brief History of Library Technology

Abstract

The importance of technology in library operations is critical to understanding the modern library. Not only must one be comfortable with technical skills, but the management of personnel issues is equally critical for success. The history of library automation has changed tremendously over the years, especially with the introduction of computers in the library.

Keywords

Technology; people skills; automation history; classification; computers in libraries

Brief history of library automation

From the very beginning of libraries, the control of collections has been the main goal of librarians. All the way back to antiquity, the ancient library of Alexandria maintained a listing of the papyrus rolls that it held, adding details to each annotation to form a unique description (Lerner, 2009, p. 16). In the Middle Ages, this practice of printed lists continued with the lists serving more as an inventory for these libraries, often housed in monasteries and that were only intended for the sole use of the monks (Lerner, 2009, p. 33). Lending of books between religious groups was done on a very limited basis (mostly for the purpose of copying) with no public access provided to these collections (Lerner, 2009, pp. 34–35).

As collections grew in size and scope, so too did the number of institutions that were maintaining their own library collections. The growth of cities and universities in the Renaissance spurred this increase as well as the number of wealthy private individuals (including royal courts) who were building their own collections. Palaces such as Versailles in France and the Winter Palace in Russia had magnificent libraries and extensive collections that often served as the basis for future national libraries.

Classification

Needing to provide better access to this growing number of books on diverse subjects, a system had to be devised to supplement the printed inventory lists of the library’s contents. Arranging materials by subjects seemed to be the obvious conclusion and in 1605 Francis Bacon divided all human knowledge into three kinds of science: history (memory), poesy (imagination), and philosophy (reason) (Lerner, 2009, p. 120).

These three major categories were added to and subdivided over the years as new subjects not envisioned by the original author were being written about. The other main challenge to this evolving classification scheme was that libraries, each one operating independently, were inconsistent in how they applied the categories. There remained the need for a standard system of classification that could be readily adapted by many libraries to promote uniformity and efficiency.

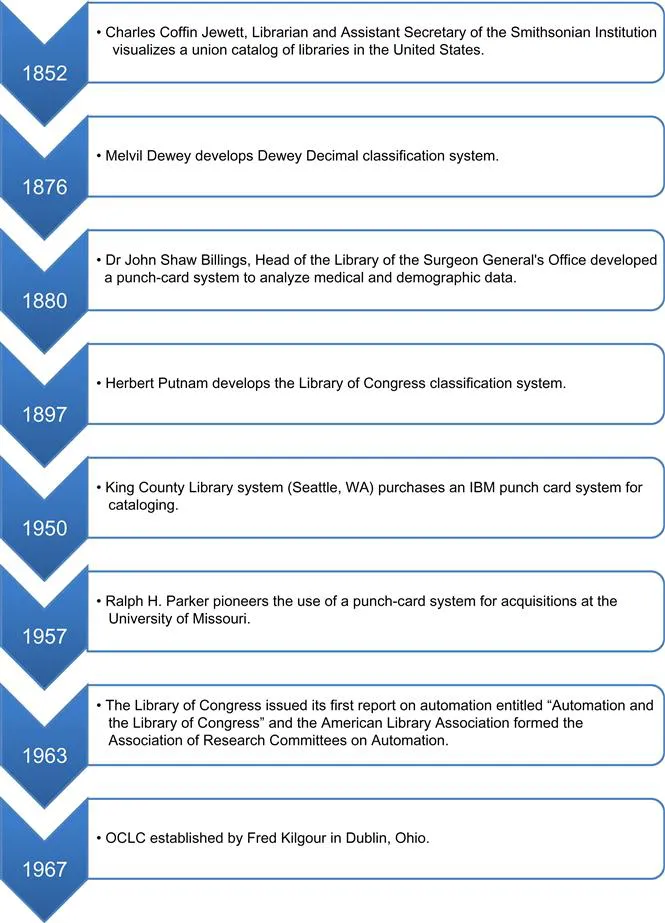

One of the great pioneers in this field was Melvil Dewey (1851–1931), the father of the Dewey Decimal System, used by many libraries throughout the world. Dewey developed a system in which each subject classification was broken down by a numerical code with further subdivisions under each class. Under this system, each book was assigned a unique call number, making it easy to shelve and retrieve, all grouped within the same subject area. This was a huge improvement over previous systems and allowed libraries to more easily accommodate the growth of their collections and the introduction of new subject areas. This idea of dividing the world of knowledge into increasingly complex subject areas led to the more specialized Universal Decimal Classification and the Library of Congress (LC) Classification System.

It is at this point that the first card catalogs were introduced, with each book having an individual card in the catalog. Now, instead of consulting a dated printed list of library titles, patrons could look up their favorite materials in a catalog that was not static but could be added to indefinitely as new materials were purchased for the library. With the wide publication of the Dewey system and the standardization of cataloging, other libraries too began to adopt the same classifications for their materials.

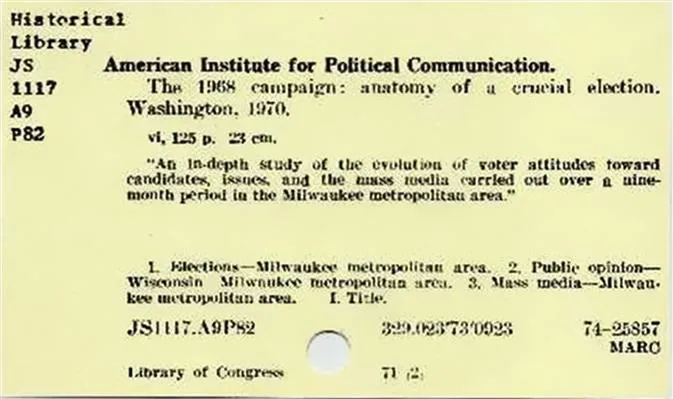

Since the LC was serving as the unofficial national library of the United States, it had one of the largest collections and staffs to catalog materials for its collections. In 1902, the LC began selling copies of its printed catalog cards to other libraries, saving individual libraries the expense of having to catalog materials already owned by LC (Lerner, 2009, p. 179). This was one of the first steps in terms of library automation, even though it involved printed materials and was well before modern technology entered the picture. The idea of library cooperation and resource sharing were slowly becoming one of the cornerstones of how libraries operated (Figure 1.1).

The development of computers led to the next steps in library automation, mirroring what was happening in the rest of the business and government information world. Society was being changed by the advent of computing and libraries wanted to take advantage of this new technology to help them manage their growing collections, especially as the economy and funding for libraries grew during the 1960s.

As library collections grew, the necessity of finding a way to be more efficient became even more acute, especially with the labor-intensive aspects of library operations. One of the most expensive sources of labor costs for most libraries was the cataloging operation, in which each item had to be described, both physically and intellectually, before it could be added to the collection. Creating an original cataloging record required highly trained staff and time-intensive procedures. Multiply this cost by the number of libraries with their own team of catalogers and it is readily apparent that this cost would be difficult to maintain.

As has been already noted, the development of shared classification schemes allowed libraries to share cataloging records with other libraries through printed cards. But with the advent of automated library systems, it became possible for libraries to actually share their catalog records directly with each other without waiting for a third party supplier to produce cards and mail them out. The development of automated systems for the sharing of bibliographic records resulted in the development of bibliographic utilities, an important milestone in the library automation world.

The most famous bibliographic utility is OCLC, established in 1967. Originally conceived as the Ohio College Library Center, a statewide bibliographic database, it quickly grew beyond its geographic area to encompass bibliographic records for other national (and later international) libraries. It was followed by the Research Libraries Information Network (RLIN) and the Western Library Network (WLN) both of who were serving a similar function to OCLC.

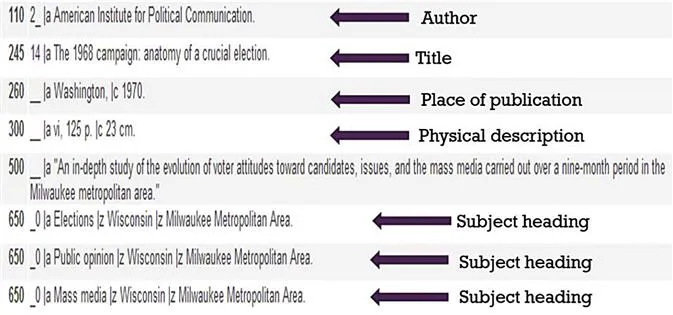

The establishment of these bibliographic utilities would not have been possible without the development of bibliographic record standards, as each library would need to adhere to a common standard for sharing records. Pioneered by the LC in 1961, the MAchine Readable Cataloging (MARC) format was developed and quickly became the standard for most American libraries. The adoption of MARC standards meant that libraries could contribute to and copy records from the bibliographic utilities to their local catalogs, secure in the knowledge that all records met the agreed-upon standards. This was one of the most important developments in library automation as one of the most expensive jobs in the library operations was greatly simplified and expedited through the sharing of bibliographic records on a global scale (Figure 1.2).

Following the automation of the cataloging operation and the continued growth of the computer industry, other aspects of library operations became targets for automation. Although some libraries had experimented with punch card systems for circulation purposes, most library record-keeping was still done manually, with a mixture of professional and nonprofessional staff. Starting with the technical services operations, the Northwestern Online Total Integrated System (NOTIS) was developed by Northwestern University in 1968 as the first integrated library system. This system was one of the first to link circulation functions and technical services functions in one unified system, followed by the development of an online public access catalog in 1985 (Figure 1.3).

The success of NOTIS and its availability as a library system for purchase launched a revolution in the library world. No longer did each library have to have an in-house programming staff and information technology (IT) support to develop its own library software; with the advent of NOTIS and similar systems, a library could purchase software for its operations from an independent vendor. This led to the development of an automation marketplace of many vendors, offering a variety of integrated and stand-alone systems to the library world.

When looking back at the more recent history of library automation, it is clear that for over 100 years, librarians have been attempting to discover ways to use their current state-of-the-art technology to expand library services. Often these technologies were not the final solutions but provided instead a stepping-stone to the adoption of solutions that took advantage of new technological developments. Some of the highlights from library automation history are shown in Figure 1.4.

The ability to automate library functions with an integrated library system is only possible when the library has data stored in an electronic format that can be utilized by the system. Many libraries made the transition from a paper-based storage system to electronic records upon the purchase of a new system, necessitating new workflows and procedures. A complete understanding of the record types used in modern libraries and examples of typical workflows is critical to anyone wanting to be familiar with the development of integrated systems.

2

Record Types and Print Library Workflows

Abstract

Understanding the key components of library operations, especially the discovery layer, highlights how technology has transformed library organizations and staff. A thorough knowledge of the types of records created in a library and the movement of materials through the library are necessary before undertaking any automation project. Also important to understand is what types of records will need conversion from a manual format to an ele...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Author

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1. Brief History of Library Technology

- 2. Record Types and Print Library Workflows

- 3. Electronic Resources

- 4. Systems Librarians

- 5. Project Management

- 6. Change Management

- 7. Needs Assessment and the Library Automation Marketplace

- 8. Open Source

- 9. Decision Trees and Consultants

- 10. Request for Proposal

- 11. Data Migration, Retrospective Conversion, and Barcodes

- 12. Staff Training and Troubleshooting

- 13. Staffing the Libraries of the Future

- 14. The Library Transformation in the Digital Age

- Conclusion

- Appendix. The Orbis-Cascade Project

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Selecting and Implementing an Integrated Library System by Richard M Jost in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Library & Information Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.