Andrea Baucon*,†, 1, Emese Bordy‡, Titus Brustur§, Luis A. Buatois¶, Tyron Cunningham||, Chirananda De#, Christoffer Duffin**, Fabrizio Felletti†, Christian Gaillard††, Bin Hu‡‡, Lei Hu‡‡, Sören Jensen§§, Dirk Knaust¶¶, Martin Lockley||||, Pat Lowe##, Adrienne Mayor***, Eduardo Mayoral†††, Radek Mikulᚇ‡‡, Giovanni Muttoni†, Carlos Neto de Carvalho*, S. George Pemberton§§§, John Pollard¶¶¶, Andrew K. Rindsberg||||||, Ana Santos###, Koji Seike****, Hui-bo Song‡‡, Susan Turner††††, Alfred Uchman‡‡‡‡, Yuan-yuan Wang‡‡, Gong Yi-ming‡‡, Lu Zhang‡‡ and Wen-tao Zhang‡‡

*UNESCO Geopark Naturtejo Meseta Meridional, Geology and Palaeontology Office, Centro Cultural Raiano, Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal

†Università degli Studi di Milano, Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Via Mangiagalli, Milano, Italy

‡Geology Department, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

§National Institute of Marine Geology and Geo-ecology (GEOECOMAR), Bucharest, Romania

¶Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada

||International Society of Professional Trackers, Missouri, Cameron, USA

#Palaeontology Division-1, CHQ, Geological Survey of India, Kolkata, India

**146 Church Hill Road, Sutton, Surrey, United Kingdom

††Paléoenvironments et Paléobiosphère, UFR, Sciences de la Terre, Université claud Bernard Lyon 1, Villeurbanne cedex, France

‡‡Key Laboratory of Biogenic Traces and Sedimentary Minerals of Henan Province, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province, China

§§Área de Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain

¶¶Statoil ASA, Stavanger, Norway

||||Dinosaur Tracks Museum, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA

##Backroom press, Broome, Western Australia

***Classics Department, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA

†††Departamento de Geodinámica y Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales, Campus de El Carmen, Universidad de Huelva, Huelva, Spain

‡‡‡Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Praha, Czech Republic

§§§Ichnology Research Group, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

¶¶¶School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, United Kingdom

||||||University of West Alabama, Livingston, USA

###Departamento de Geodinámica y Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales, Campus de El Carmen, Universidad de Huelva, Huelva, Spain

****Department of Earth and Planetary Science, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan

††††Geology & Palaeontology, Queensland Museum and Monash University School of Geosciences, Hendra, Queensland, Australia

‡‡‡‡Institute of Geological Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Although the concept of ichnology as a single coherent field arose in the nineteenth century, the endeavor of understanding traces is old as civilization and involved cultural areas worldwide. In fact, fossil and recent traces were recognized since prehistoric times and their study emerged from the European Renaissance. This progression, from empirical knowledge toward the modern concepts of ichnology, formed a major research field which developed on a global scale. This report outlines the history of ichnology by (1) exploring the individual cultural areas, (2) tracing a comprehensive bibliographic database, and (3) analyzing the evolution of ichnology semiquantitatively and in a graphical form (“tree of ichnology”). The results form a review and synthesis of the history of ichnology, establishing the individual and integrated importance of the different ichnological schools in the world.

1 Introduction

Among one and another rock layer, there are the traces of the worms that crawled in them when they were not yet dry.

Leonardo da Vinci, Leicester Codex, folio 10 v

Since the beginnings of ichnology, trace fossils have been recognized for their twofold nature as biological and sedimentological objects. As a discipline studying biogenic sedimentary structures, ichnology proved to be very important for paleontology and sedimentary geology as well.

The tendency of applying trace fossils in the characterization of past depositional environments manifested itself very early. Leonardo da Vinci used trace fossils to prove the marine origin of the sedimentary successions of the Apennines (Baucon, 2010), but it took ichnology four centuries to develop comprehensive and precise scientific tools for the needs of paleoenvironmental analysis. Nowadays, ichnology is a matter of great interest due to the huge spectrum of potential applications such as facies interpretation, paleoenvironmental reconstruction and recognition of discontinuities, prospecting and exploration of hydrocarbon resources.

This chapter aims to delineate the progression from empirical knowledge toward the modern concepts of ichnology, with particular regard to the application of ichnology to facies analysis. This has guided our areas of emphasis so that, for example, we give invertebrate traces a greater allocation of space than vertebrate traces because they find more sedimentological applications.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide information not only about ichnologists and their theories but also why they developed an idea as they did. For this reason, particular attention has been given to the specific social and historical circumstances surrounding the individual line of thought. Similarly, we followed a global perspective, based on the belief in the international character of ichnology.

Tracing the global history of ichnology is possible through the texts which have survived, hence the necessity of compiling a comprehensive bibliographic database on the history of ichnology (see the Supplementary Material: http://booksite.elsevier.com/9780444538130). The purpose is to show semiquantitatively the chronological relationships among various branches of ichnology based upon similarities and differences in the interpretation of traces.

2 The Ages of Ichnology

Although the study of trace fossils is an important field for the solution of fundamental and applied problems of geology, there is a lack of general historical overviews. With the exception of studies on specific episodes and geographical areas, the only general historical accounts are those of Osgood (1970, 1975; invertebrate ichnology) and Sarjeant (1987; vertebrate ichnology).

Osgood (1975) attempted to subdivide the history of ichnology on the basis of periods of time with relatively stable characteristics:

1. Age of Fucoids (1823–1881): This stage started with Brongniart (1823), who considered invertebrate trace fossils as fucoids, or seaweed. During this historical stage, the botanical interpretation dominated the scientific view of trace fossils.

2. Period of Reaction (or Age of Controversy) (1881–1925): Based on analogies with modern traces, Nathorst (1881) argued that many fucoids were trace fossils. This aroused a consistent debate, with prominent scientists like Lebesconte and de Saporta supporting the botanical interpretation.

3. Development of the Modern Approach (1925–1953): This stage started with the establishment of the Senckenberg Laboratory, a marine institute devoted to neoichnology (Cadée and Goldring, 2007). The geologists of the period agreed about the ichnological nature of trace fossils, opening the avenues to the decisive steps toward modern ichnology.

In more recent times, two historical stages were added to Osgood’s classical periods: Pemberton et al. (2007) recognized a Modern Era of Ichnology, extending from 1953 to the present day. This period saw the foundation of the central concepts of modern ichnology, starting with Seilacher’s (1953) seminal publication on the methods of ichnology. Recently, Baucon (2010) established the Age of Naturalists, spanning roughly the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. During this stage, several Renaissance intellectuals depicted and studied trace fossils, although ichnology existed as disconnected ideas about traces. Holding these stages as a chronological reference, this chapter will explore the evolution in the study of trace fossils, from Paleolithic times to the present.

3 From Paleolithic Times to Greco-Roman Antiquity

Archeological evidence indicates that humans have recognized trace fossils since Paleolithic times. Bioeroded Miocene mollusks are commonly found within the cultural layers of Pavlov and Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic, Late Paleolithic, 29,000–24,000 years ago; Fig. 1A). Statistical data from the primary collection sites indicate that humans selectively collected mollusks with bioerosional trace fossils (Oichnus) in order to use them as items of personal adornment (i.e., segments of collars; Jarošová et al., 2004 in Supplementary Material: http://booksite.elsevier.com/9780444538130).

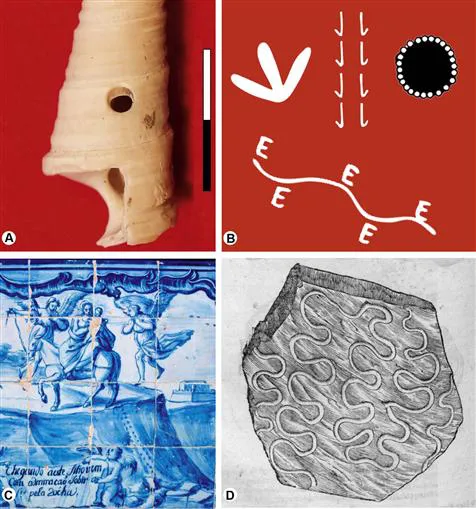

Figure 1 Beginnings of ichnology. (A) Miocene bioeroded mollusk found within Paleolithic cultural layers. Scale bar: 1 cm (Dolní Věstonice II, Czech Republic; Jarošová et al., 2004 in Supplementary Material: http://booksite.elsevier.com/9780444538130). (B) Ichnological symbols commonly used in Australian Aboriginal art. Clockwise from top left: emu footprint, kangaroo track, burrow, goanna (monitor lizard) track. (C) Eighteenth century azulejo (painted, glazed ceramic tilework) depicting Nossa Senhora da Pedra Mua (Our Lady of the Mule Stone). A set of footprints is clearly visible on the sea cliff. Memory Chapel, Cabo Espichel (Portugal). (D) Trace fossils in the Italian Renaissance: Cosmorhaphe, as represented in Aldrovandi’s Musaeum Metallicum.

Such archeological evidence shows that trace fossils were a subject of ancient interest for humans, although it gives no information about their interpretation in past hunter/gatherer societies. In this regard, anthropological analogy with modern indigenous populations represents a valuable tool of analysis. As one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world, Australian Aborigines provide an exceptional insight in the anthropology of biogenic traces (Lowe, 2002). Native Australian people developed remarkable neoichnological abilities, gaining a detailed understanding of animal behavior through the interpretation of tracks and burrows (Ellena and Escalante, 2007). The crucial role of tracking is mirrored in the rich vocabulary for traces and their conditions, often without equivalents in European languages. In Walmajarri language, tracks left after rain are called murrmarti, and a goanna burrow in soft sand that is too deep for the animal to be reached is called purruj. Similarly, Aboriginal art has a visual vocabulary for traces, consisting of standard symbols for each kind of track (Fig. 1B).

Trace fossils are also an object of interest for Australian Aborigines. Dinosaur tracks are part of the Ngarrangkarni (or “Dreamtime”), a mythical past when giant ancestor beings left traces of their exploits, shaping the landscape to its present form. Native people attribute theropod tracks to an enormous feathered “Emu-man”, M...