This is a test

- 531 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sleep and Health

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Sleep and Health provides an accessible yet comprehensive overview of the relationship between sleep and health at the individual, community and population levels, as well as a discussion of the implications for public health, public policy and interventions. Based on a firm foundation in many areas of sleep health research, this text further provides introductions to each sub-area of the field and a summary of the current research for each area. This book serves as a resource for those interested in learning about the growing field of sleep health research, including sections on social determinants, cardiovascular disease, cognitive functioning, health behavior theory, smoking, and more.

- Highlights the important role of sleep across a wide range of topic areas

- Addresses important topics such as sleep disparities, sleep and cardiometabolic disease risk, real-world effects of sleep deprivation, and public policy implications of poor sleep

- Contains accessible reviews that point to relevant literature in often-overlooked areas, serving as a helpful guide to all relevant information on this broad topic area

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sleep and Health by Michael A. Grandner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

General concepts in sleep health

Chapter 1

The basics of sleep physiology and behavior

Andrew S. Tubbsa; Hannah K. Dollishb; Fabian Fernandezb; Michael A. Grandnerc a Department of Psychiatry, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

b Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

c Sleep and Health Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ, United States

b Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

c Sleep and Health Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ, United States

Abstract

Sleep is an essential element of human health, supporting a wide range of systems including immune function, metabolism, cognition, and emotional regulation. To understand everything that sleep does, however, it is necessary to understand what sleep is. This chapter provides that foundation by discussing the conceptualization, physiology, and measurement of sleep.

Keywords

Sleep need; Sleep ability; Sleep opportunity; Sleep physiology; Polysomnography; Actigraphy; Non-REM sleep; REM sleep; Circadian rhythms; Sleep measurement

Introduction

Sleep is an essential element of human health, supporting a wide range of systems including immune function, metabolism, cognition, and emotional regulation. To understand everything that sleep does, however, it is necessary to understand what sleep is. This chapter provides that foundation by discussing the conceptualization, physiology, and measurement of sleep.

The definition of sleep

Sleep is a naturally recurring and reversible biobehavioral state characterized by relative immobility, perceptual disengagement, and subdued consciousness. As a predictable and easily reversible phenomenon, sleep is distinct from states of anesthesia and coma, which typically involve the absence or suppression of neural activity. Additionally, proper sleep involves a dynamic interaction between voluntary decisions and involuntary biological activities. Turning off the lights, reducing noise, and laying down are voluntary behaviors, but the result is an involuntary increase in melatonin and a series of shifts in the activity patterns of the brain throughout the night. Sleep ultimately depends on this collaboration between behavior and biology, and a deficit in either will disrupt sleep.

Conceptualizing sleep as a health behavior

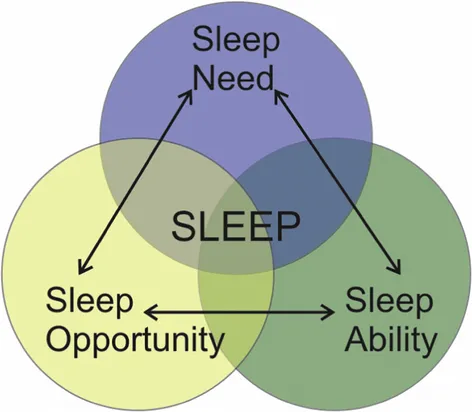

A health behavior is an action (or omission) by an individual that impacts their health. Conceptualizing sleep as a health behavior is useful because it highlights how behavior and neurobiology interact, and how individuals can modify their health through sleep. Viewed in this way, sleep can be divided into three processes: sleep need, sleep ability, and sleep opportunity. These processes are diagramed in Fig. 1.1.

Sleep need is the biological requirement for sleep, or the minimal amount of rest the body requires to prepare for the next day. This need is defined by individual genetics and physiology and does not change after losing a night of sleep or oversleeping on the weekends. Unfortunately, there is no standard method for measuring sleep need. While epidemiological studies suggest an average of 7–8 h for healthy adults, some individuals naturally need more sleep (e.g., children and adolescents), while some need less. Sleep need represents the core motivation for engaging in sleep, and consistently failing to meet this need can promote cardiometabolic disease, impair cognitive functioning, and increase risk for psychiatric disorders.

The only way to satisfy sleep need is to sleep. The amount of sleep an individual can achieve is known as sleep ability and is approximated by total calculated sleep time. Unlike sleep need, sleep ability can change from one night to the next depending on life circumstances. Stress, a cold, or the death of a loved one can reduce sleep ability, while one night of sleep deprivation can increase sleep ability the following evening. Thus, while sleep ability cannot be directly controlled, it can be influenced by behavior.

Whereas sleep ability is correlated to the amount of time one spends sleeping, sleep opportunity is the amount of time the person makes available for sleep. Sleep opportunity is measured by the amount of time the person stays in bed (although time spent in habitual “bedtime” activities like reading a book could theoretically be incorporated). Unlike the two previous processes, sleep opportunity is under conscious control and is the most vulnerable to environmental factors. This is illustrated by a trauma resident on a 24-h call. Fatigue accumulates over the course of the shift, slowly increasing the resident’s sleep ability. However, sleep opportunity is negligible, since the resident must be ready at a moment’s notice to respond to a life-threatening crisis.

While these three sleep processes can be described independently, in the real-world they work together to control sleep. Sleep need motivates the creation of sleep opportunity, which provides a context for sleep ability to produce sleep—thus satisfying sleep need and reinforcing the methods used to create sleep opportunity in the first place.

Conceptualizing sleep as a physiological process

Sleep involves a progression of neurophysiological changes in the brain. These changes are grouped (somewhat artificially) into stages based on scoring convention. To explore these changes, this section will briefly describe wakefulness and then proceed to give a description of each of the sleep stages.

Wakefulness

During wake, the brain is engaged in numerous activities, many of which are unrelated to one another. For example, someone might be watching a TV show while listening for the sound of a car in the rain and thinking about whether there is enough food in the refrigerator for lunch tomorrow. The aggregated electrical activity produced by these processes can be observed using electroencephalography (EEG), which would show a high-frequency, low-amplitude signal traveling across the surface of the brain (Fig. 1.2). To understand what this means, imagine a crowd cheering in a sports stadium. Everyone is shouting at different times. This means that while someone is always cheering (high frequency), it is impossible to discern individual words because everyone’s words are drowning each other out (low amplitude). Coming back to the brain, a high frequency signal means many different processes are present in the circuitry of the brain, but the timing of these processes is scattered. Because this activity is widespread, it is hard to resolve any one particular process, resulting in a low amplitude signal. The beta frequency is the classic frequency of active wake and ranges from 12 to 30 Hz (cycles per second). When subjects lay down and close their eyes, electrical activity generally slows to an alpha frequency (8.5–12 Hz), which indicates that the person is awake but not necessarily attending to their surroundings (Fig. 1.2). Along with electrical activity, wakefulness is characterized by high levels of arousal neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin. There is also increased autonomic activity; heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure are constantly responding and adapting to changes in the body and the environment throughout the day.

NREM sleep: General overview

The first half of the sleep cycle can be divided into three distinct stages of nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, aptly named Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3. Electrical activity throughout the brain decreases in frequency and increases in amplitude at each progressive stage. This reflects a reduction in overall neural activity, but an increasing coordination among neurons (i.e., enhanced oscillation). Recalling the example from above, imagine if the crowd slowly coordinated their cheering. At first, the sound would still be noisy and unintelligible. However, once everyone followed along, a wave of quiet alternating with cheering would emerge. The number of cheers would decrease (lower frequency), but the volume and clarity of each cheer would steadily increase (higher amplitude). By the end of NREM the electrical activit...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: General concepts in sleep health

- Part II: Contextual factors related to sleep

- Part III: Addressing sleep health at the community and population level

- Part IV: Sleep duration and cardiometabolic disease risk

- Part V: Sleep and behavioral health

- Part VI: Sleep loss and neurocognitive function

- Part VII: Public health implications of sleep disorders

- Part VIII: Sleep health in children and adolescents

- Part IX: Economic and public policy implications of sleep health

- Index