![]()

Valuing the Ocean

An Introduction

Kevin J. Noone∗, Ussif Rashid Sumaila§ and Robert J. Diaz†, ∗Department of Applied Environmental Science, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, §Fisheries Economics Research Unit, Fisheries Centre, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, †Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Point, Virginia, USA

Take a deep breath. Now take one more. The oxygen in one of those breaths came from organisms in the ocean. The oceans are cornerstones of our life support system. They provide many essential ecosystem goods and services essential for humanity, including food, medicinal products, carbon storage, and roughly half the oxygen we breathe. Oceans also support many economic activities including tourism and recreation, commercial and subsistence fisheries, aquaculture, transportation, and mineral resource extraction. They contribute to local livelihoods as well as to national economies and foreign exchange receipts, government tax revenues, and employment. The global ocean is also integral to the earth’s climate story, particularly since oceanic heat storage and ocean currents directly influence global climatic conditions.

Despite their central importance to the human endeavor, the oceans are essentially invisible to most of society. Even those of us fortunate enough to live near the sea seldom take the opportunity to look under the surface.

The oceans are under a number of coupled threats unprecedented in modern human history. Sea levels are rising, the oceans are warming and acidifying, oxygen is disappearing in many areas, the seas are becoming more polluted, and we are extracting many marine resources at unsustainable rates. The situation does not have to be this way; but in order to avoid further damage to the oceans, to the life they hold, and to the goods and services they provide, we must develop a holistic view of how our actions impact them. We must create a framework for ocean management in the Anthropocene—the current epoch in which we humans are the dominant driver of global environmental change (Crutzen, 2002).

Purpose and Scope of the Book

The aims of this book are to:

(a) summarize the current state of the science for a number of marine-related threats (described in more detail in the following section);

(b) examine these threats to the oceans both individually and collectively;

(c) provide gross estimates of the economic and societal impacts of these threats; and

(d) deliver high-level recommendations for what is still needed to stimulate the development of policies that would help to move toward sustainable use of marine resources and services.

Threats to the Oceans: Current State of the Science

Chapters 2-7 review the state of the science for several threats to the global oceans: acidification, warming, hypoxia, sea level rise, pollution, and overuse of marine resources. Each of the chapters summarizes the latest research in each area and presents it in a way that is accessible to specialists and nonspecialists alike. There is a substantial literature on each of these issues; but thus far, these issues have been researched and reported largely separately. In this book, we want to have concise reviews of the state of the science in these areas all in one place.

A Holistic View of Threats to the Oceans

A result of the fact that research on these issues has been to a large degree done separately, we have little knowledge of the extent to which these threats interact with and feed back on each other. Chapter 8 addresses questions like:

• What are the possible feedback processes between these threats?

• Do any of the threats amplify or dampen others?

• How do local, regional, and global stressors interact?

• What sort of policy and management strategies do we need to account for multiple, interacting stressors?

Chapter 8 will show examples of how interactions between multiple stressors act across different scales and how these interactions require new approaches to marine resource management.

Chapter 9 discusses different ways to plan for the future in the context of marine resources. In many environmental areas, society has a tendency of planning for a “plain vanilla” future—a predictable, gradually changing, middle-of-the road scenario. Here, we contrast three different scenarios approaches: one used in the climate change research community, one in the private sector, and one from the military domain. Each of these approaches has its own strengths and weaknesses, but by contrasting them, we can perhaps learn how to better prepare for a future that may involve hard to predict low-probability, high impact events. From a holistic point of view, we need to develop the capability to anticipate and plan for surprises—or “unknown unknowns.”

Differential Analysis for Future Scenarios

To be relevant for policy decisions, the economic analysis will be centered on differences between two future scenarios. Past losses are no longer changeable with current or future decisions—they will not be included in this analysis. In order to frame our discussions of the future oceans, we will use two of the scenarios currently being employed in the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

As discussed in Chapter 9, previous assessment reports of the IPCC have used scenarios—storylines of socioeconomic and demographic development—to create estimates of human resource use and emissions into the future. As an example, the third and fourth assessment reports (AR3 and AR4, respectively) used a set of scenarios described in detail in the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) (Nakicenovic et al., 2000); these have become known as the SRES scenarios.

A new approach will be taken for the 5th IPCC Assessment Report (AR5).

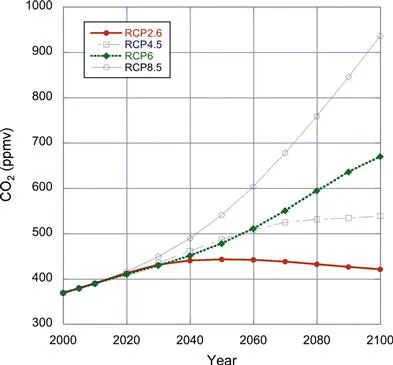

This new approach was devised to enable better integration and feedback between the impacts and climate research communities, as well as to “start in the middle” in order to minimize uncertainties (Hibbard et al., 2007; Moss et al., 2010). It also enables the research community to update the scenarios on which climate studies are based after nearly a decade of new information on economic development, technological advances, and chances in climate and environmental factors. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations for the four different “representative concentration pathways” (RCPs) are shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations for the four RCPs. IMAGE, Integrated Model to Assess the Global Environment; GCAM, Global Change Assessment Model; AIM, Asia-Pacific Integrated Model; and MESSAGE, Model for Energy Supply Strategy Alternatives and their General Environmental Impact.

Each of these four scenarios has been calculated using a different integrated assessment model, and each model has different input assumptions about, e.g., population development, demographics, energy, and resource use. For the purposes of the 5th IPCC Assessment Report, these concentration profiles are starting points with which to explore the range of different socioeconomic development pathways that are consistent with the profiles, as well as to explore the range of impacts, adaptation and mitigation options that are possible. In this sense, while the references in the previous paragraph give details about the assumptions behind the different RCPs, detailed data on the full range of parameters for these profiles are not yet available. For the purposes of this book, if the data needed for our analysis are not available from one of the sources cited above, we will use data from the SRES scenario that most closely resemble the case in question.

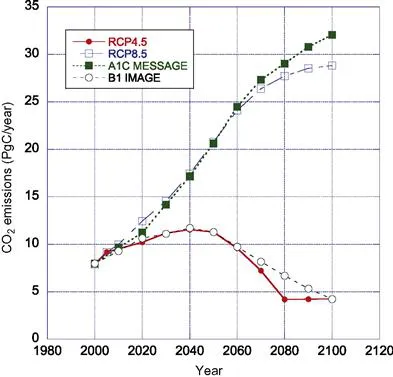

One example of the correspondence between atmospheric CO2 concentrations between the new RCPs and the previous SRES scenarios is shown in Figure 1.2, which compares the concentrations between two RCPs (4.5 and 8.5) and two SRES scenarios (the A1C scenario calculated using the MESSAGE model, and the B1 scenario calculated using the IMAGE model). While not the same, the concentration pathways are similar in these two cases, meaning that the socioeconomic, technological, and demographic assumptions behind the SRES scenario calculations are roughly consistent with the RCP concentration profiles.

Figure 1.2 Comparison of CO2 emissions for two RCPs and two SRES scenarios.

For the purposes of this book, we want to use two different scenarios to compare and contrast the potential impacts of following two different kinds of decision pathways in the future and to provide the basis for calculating differences in the economic consequences of taking these different decision pathways. In this regard, the scenarios should have a few important characteristics:

• One of the scenarios should reflect a decision pathway designed to reflect human activities having a relatively modest environmental impact;

• The second scenario should be one in which the human impact on the environment is large, but not disastrously so;

• The differences between the scenarios should be sufficiently large that clear differences in impacts can be discerned, thereby providing the possibility of clearly differentiating the benefits and detriments of different policy choices.

In light of these criteria, RCP2.6 and RCP6 are the most appropriate for our analysis (van Vuuren et al., 2011). The RCP2.6 scenario is one that would require substantial economic and societal investments, but one that would likely put us on what would be a more sustainable development pathway than our current one. This scenario provides us with what can be interpreted as a desired outcome—at least in an environmental and societal sense. We chose RCP6 in order to provide a clear contrast between the end results of the different decisions pathways by the end...