eBook - ePub

About this book

Neuroepidemiology covers the foundations of neuroepidemiological research and the epidemiology of disorders primarily affecting the nervous system, as well as those originating outside the nervous system. The etiology of many important central nervous system disorders remains elusive. Even with diseases where the key risk determinants have been identified, better prevention and therapy is needed to reduce high incidence and mortality. Although evolving technologies for studying disease provide opportunities for such, it is essential for researchers and clinicians to understand how best to apply such technology in the context of carefully characterized patient populations.

By paying special attention to methodological approaches, this volume prepares new investigators from a variety of disciplines to conduct epidemiological studies in order to discern the etiologic factors and underlying mechanisms that influence the onset, progression, and recurrence of CNS disorders and diseases. The book also provides current information on methodological approaches for clinical neurologists seeking to expand their knowledge in research.

- Includes coverage of the foundations of neuroepidemiological research and the epidemiology of disorders primarily affecting the nervous system, as well as those originating outside the nervous system

- Describes the most recent methodologies to define and quantify the burden of CNS disorders and to understand the underlying mechanisms, with neuroimaging and molecular methods receiving particular emphasis

- Offers extensive description of those neurological conditions that are secondary to other diseases whose incidence is on the rise because of longer survival rates

- Features chapters authored by leaders in the field from around the globe

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Epidemiology for the clinical neurologist

M.E. Jacob1; M. Ganguli2,* 1 Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

2 Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

* Correspondence to: Mary Ganguli, MD, MPH, WPIC, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh PA 15213, USA. Tel: + 1-412-647-6516 email address: [email protected]

2 Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

* Correspondence to: Mary Ganguli, MD, MPH, WPIC, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh PA 15213, USA. Tel: + 1-412-647-6516 email address: [email protected]

Abstract

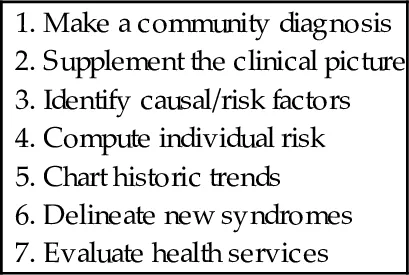

Epidemiology is a foundation of all clinical and public health research and practice. Epidemiology serves seven important uses for the advancement of medicine and public health. It enables community diagnosis by quantifying risk factors and diseases in the community; completes the clinical picture of disease by revealing the entire distribution of disease and presenting meaningful population averages from representative samples; identifies risk factors for disease by detecting and quantifying associations between exposures and disease and evaluating causal hypotheses; computes individual risk to identify high-risk groups to whom preventive interventions can be targeted; evaluates historic trends that monitor disease over time and provide clues to etiology; delineates new syndromes and disease subtypes not previously apparent in clinical settings, helping to streamline effective disease management; and investigates the effects of health services on population health to identify effective public health interventions. The clinician with a grasp of epidemiologic principles is in a position to critically evaluate the research literature, to apply it to clinical practice, and to undertake valid clinical epidemiology research with patients in clinical settings.

Keywords

epidemiology; incidence; prevalence; sampling; relative risk; odds ratio; bias; confounding; sensitivity; specificity; cohort effect

The neurologist is called to the emergency department to see a patient with acute-onset, left-sided weakness. While conducting the neurologic examination, she obtains the patient's history and learns that he has a long history of hypertension and also of heavy smoking and alcohol intake. Soon, she is initiating treatment, ordering the appropriate investigations, and explaining to the patient and family the diagnosis of a stroke, the likely causes, and the prognosis. This standard clinical practice is not based solely on her anecdotal experience with her own previous patients or even her knowledge of the clinical features of stroke. Also entering into her clinical assessment, and her conversation with her patient and family, is her awareness of the “distribution and determinants” of stroke in large numbers of people, i.e., the epidemiology of stroke (Davis et al., 1987; Shinton and Beevers, 1989; Sacco et al., 1999).

As in the above example, and as we will show throughout this chapter, epidemiology is a foundation of clinical and public health practice. The thoughtful clinician with a grasp of epidemiologic principles is able to critically evaluate research that is being disseminated and also to incorporate findings into clinical practice. The clinical epidemiologist, who undertakes epidemiologic research among patients in the clinical setting, is in a unique position to advance knowledge through scientific research on vital clinical questions.

What is epidemiology?

The word epidemiology is derived from the Greek terms epi meaning “on” or “upon,” demos meaning “people,” and logos, meaning “study.” Epidemiology is classically defined as: (1) the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states and events in populations; and (2) the application of this study to the prevention and control of health problems. The field of epidemiology, as we know it, originated in a landmark study of a cholera epidemic by John Snow in England, in the 1850s. By establishing that the disease was being spread through London via ingestion of contaminated water from the now infamous Broad Street pump, Snow revolutionized the understanding of the pathogenesis of cholera. Since then, epidemiologic research has led to game-changing public health measures to improve the health of populations, ranging from smallpox vaccination that eradicated the disease, to multidrug antiretroviral treatment which has transformed HIV-AIDS from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic disease.

Beyond investigating communicable diseases, epidemiology has also moved on to understanding chronic disease at the population level, applying the same principles. Technologic advancement has led to the emergence of subspecialty fields like molecular epidemiology and geospatial epidemiology. However, translating lab discoveries into measurable health benefits in the human population is not straightforward. While basic and clinical neurobiologic research has resulted in immense progress in our understanding of the human brain, it has become evident that we need to look beyond small convenience samples of patients to larger representative population samples to investigate the pathogenesis of diseases and conditions affecting the central nervous system. This motivation underlies the emerging field of “population neuroscience,” which aims to marry the knowledge base and skill sets of neuroscientists with those of population scientists (Paus, 2010; Falk et al., 2013).

Uses of epidemiology

In 1955, Jerry Morris published an article entitled “Uses of epidemiology,” which he later expanded into a textbook on epidemiology. The seven “uses” Morris listed (Table 1.1) remain remarkably relevant today, and we will use them as an outline to review the basic principles of epidemiology.

Table 1.1

The J.N. Morris “seven uses of epidemiology”

| 1. Make a community diagnosis 2. Supplement the clinical picture 3. Identify causal/risk factors 4. Compute individual risk 5. Chart historic trends 6. Delineate new syndromes 7. Evaluate health services |

Although a narrow focus on epidemiologic methods, particularly statistical methods, can potentially take away from the broader purposes of epidemiology, we will briefly outline the key methods corresponding to each “use” of epidemiology.

Making a community diagnosis

Epidemiology investigates health at the population level. A community or population diagnosis identifies the magnitude and distribution of diseases present in the community, i.e., the public health burden of disease. By helping to prioritize problems and identify at-risk subpopulations, community diagnosis is a prerequisite for formulating health policy and planning public health programs. A complete picture of the health of the community can be obtained only by collecting information on a comprehensive list of variables, including sociodemographic, health, and environmental factors related to the presence of disease. However, to the clinical epidemiologist, typically focused on a single disease, the pertinence of the “community diagnosis” is in understanding the burden of that disease in the population. Required reporting or voluntary registries for a disease can make community diagnosis easier, but since m...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Handbook of Clinical Neurology 3rd Series

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- Chapter 1: Epidemiology for the clinical neurologist

- Chapter 2: Population neuroscience

- Chapter 3: Advanced epidemiologic and analytical methods

- Chapter 4: Basics of neuroanatomy and neurophysiology

- Chapter 5: Population imaging in neuroepidemiology

- Chapter 6: Use of “omics” technologies to dissect neurologic disease

- Chapter 7: Neuropsychologic assessment

- Chapter 8: Dementias

- Chapter 9: Epidemiology of alpha-synucleinopathies: from Parkinson disease to dementia with Lewy bodies

- Chapter 10: Epidemiology of epilepsy

- Chapter 11: The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: insights to a causal cascade

- Chapter 12: Neuroepidemiology of traumatic brain injury

- Chapter 13: The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Chapter 14: Cerebrovascular disease

- Chapter 15: Peripheral neuropathies

- Chapter 16: Migraine

- Chapter 17: Neuroepidemiology of cancer and treatment-related neurocognitive dysfunction in adult-onset cancer patients and survivors

- Chapter 18: Sickle cell disease

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Neuroepidemiology by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.