This is a test

- 154 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Toxicology in Antiquity is the first in a series of short format works covering key accomplishments, scientists, and events in the broad field of toxicology, including environmental health and chemical safety. This first volume sets the tone for the series and starts at the very beginning, historically speaking, with a look at toxicology in ancient times. The book explains that before scientific research methods were developed, toxicology thrived as a very practical discipline. People living in ancient civilizations readily learned to distinguish safe substances from hazardous ones, how to avoid these hazardous substances, and how to use them to inflict harm on enemies.It also describes scholars who compiled compendia of toxic agents.

- Provides the historical background for understanding modern toxicology

- Illustrates the ways ancient civilizations learned to distinguish safe from hazardous substances, how to avoid the hazardous substances and how to use them against enemies

- Details scholars who compiled compendia of toxic agents

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access History of Toxicology and Environmental Health by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicinePreface to the Series and Volumes 1 and 2

In the realm of communicating any science, history, though critical to its progress, is typically a neglected backwater. This is unfortunate, as it can easily be the most fascinating, revealing, and accessible aspect of a subject which might otherwise hold appeal for only a highly specialized technical audience. Toxicology, the science concerned with the potentially hazardous effects of chemical, biological, and certain physical agents, has yet to be the subject of a full-scale historical treatment. Overlapping with many other sciences, it both draws from and contributes to them. Chemistry, biology, and pharmacology all intersect with toxicology. While there have been chapters devoted to history in toxicology textbooks, and journal articles have filled in bits and pieces of the historical record, this new monographic series aims to further remedy the gap by offering an extensive and systematic look at the subject from antiquity to the present.

Since ancient times, men and women have sought security of all kinds. This includes identifying and making use of beneficial substances while avoiding the harmful ones, or mitigating harm already caused. Thus, food and other natural products, independently or in combination, which promoted well-being or were found to have drug-like properties and effected cures, were readily consumed, applied, or otherwise self-administered or made available to friends and family. On the other hand, agents found to cause injury or damage—what we might call poisons today—were personally avoided although sometimes employed to wreak havoc upon one’s enemies.

While natural substances are still of toxicological concern, synthetic and industrial chemicals now predominate as the emphasis of research. Through the years, the instinctive human need to seek safety and avoid hazard has served as an unchanging foundation for toxicology, and will be explored from many angles in this series. Although largely examining the scientific underpinnings of the field, chapters will also delve into the fascinating history of toxicology and poisons in mythology, arts, society, and culture more broadly. It is a subject that has captured our collective consciousness.

The series is intentionally broad, thus the title History of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Clinical and research toxicology, environmental and occupational health, risk assessment, and epidemiology, to name but a few examples, are all fair game subjects for inclusion. Volumes 1 and 2 focus on toxicology in antiquity, taken roughly to be the period up to the fall of the Roman empire and stopping short of the Middle Ages, with which period future volumes will continue. These opening volumes will explore toxicology from the perspective of some of the great civilizations of the past, including Egypt, Greece, Rome, Mesoamerica, and China. Particular substances, such as harmful botanicals, lead, cosmetics, kohl, and hallucinogens, serve as the focus of other chapters. The role of certain individuals as either victims or practitioners of toxicity (e.g., Cleopatra, Mithridates, Alexander the Great, Socrates, and Shen Nung) serves as another thrust of these volumes.

History proves that no science is static. As Nikola Tesla said, “The history of science shows that theories are perishable. With every new truth that is revealed we get a better understanding of Nature and our conceptions and views are modified.”

Great research derives from great researchers who do not, and cannot, operate in a vacuum, but rely on the findings of their scientific forebears. To quote Sir Isaac Newton, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Welcome to this toxicological journey through time. You will surely see further and deeper and more insightfully by wafting through the waters of toxicology’s history.

Chapter 1

Toxicology in Ancient Egypt

Gonzalo M. Sanchez and W. Benson Harer

Ancient Egyptians made astute observations regarding the venomous snakes and scorpions in their land. Species identifications, effects of their bites, treatments, and prognoses are well documented and will be reviewed in this chapter. Experience would have led them to prescribe potentially toxic herbals, also well documented, in therapeutic doses. The toxicity of lead, used by Egyptians in eye paint and mascara, was not recognized.

Keywords

Apophis; magic and prescriptions; poisonous snakes; theology

1.1 Introduction

The ancient Egyptians were astute observers of natural phenomena. The ability to incorporate these observations into their beliefs about religion, politics, and magic was a major factor in the survival of their culture for so many centuries. Maat was their term for the proper order of things in the world.

Poisonous snakes and insects posed a special challenge to incorporate into a proper order of the universe. The Egyptians’ solution to incorporating them into their belief system was to be able to control them by magic. The scorpion became the goddess Selket, one of the guardians of the king’s sarcophagus. At least 10 gods and goddesses who could be protective were portrayed with serpent heads. The king, for example, converted the cobra to his protector. The horned viper was the hieroglyph word for the masculine designation as well as for the letter “f.” When the horned viper depiction in a glyph was needed in an inscription in a tomb, there was a perceived risk that it could come to life to bite the owner so it might be portrayed with the head severed from the body to be safe. Magic, or “ritual power,” was produced to protect the deceased from the most dangerous entity of all, the serpent Apophis, who threatened to block the king’s passage through the dangerous night to rebirth in the afterlife.

1.2 Snakes as Described in the Brooklyn Papyrus

The study of venomous snakebite, its chemistry, its mode of action, and the biology of the venom-producing organism are considered part of the science currently known as toxinology. The Brooklyn Museum Papyri, ca. 525–600 BCE, consist of two sections, 47,218.48 and 47,218.85, which describe individual snakes and treatment for snakebites, respectively [1]. These papyri, translated by Sauneron [2], are our major source of information on snakebites in ancient Egypt. The Brooklyn Papyri originally contained 100 paragraphs; §1–13 are missing, but presumably contained material similar to that found in §14–38. A summary of the information included therein is as follows:

Paragraphs 14–37:

1. Snake identification by name; physical characteristics of size, color, shape of the head, neck; bite marks; behavior; reptation (i.e., the manner in which it crawls); aggressiveness; and the snake’s state of alertness (some text is missing).

2. Effects of the bite, local symptoms (swelling, bleeding, pain, necrosis, and discoloration), and systemic symptoms (fever, vomiting, fainting, loss of strength, loss of consciousness, tetanization, possible seizures, and coma).

3. Prognoses and recommendation of initial treatment.

Paragraph 38: Description is of a chameleon, not a snake.

Paragraphs 39–100 include treatments for the snakebites described.

1.2.1 Snake Identification

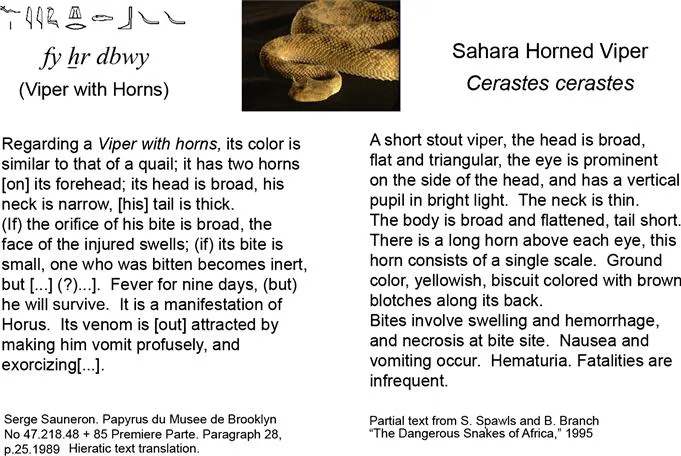

Identification of snakes from ancient Egyptian descriptions in sections 47, 218, and 48 of the Brooklyn Papyri are not established with certainty. In paragraphs 13–37, Sauneron [2, p. 164, 165] labels his identification of 18 of them as “probable” and his identification of four of them as “possible.” Likewise, Nunn and Warrell identify 13 of these and label those as tentative identifications [3, p. 183–6]. An example of certainty in snake identification is shown in parallel texts §28 [2, p. 25] and the contemporary description of Cerastes cerastes [4, p. 121–3] (Figure 1.1).

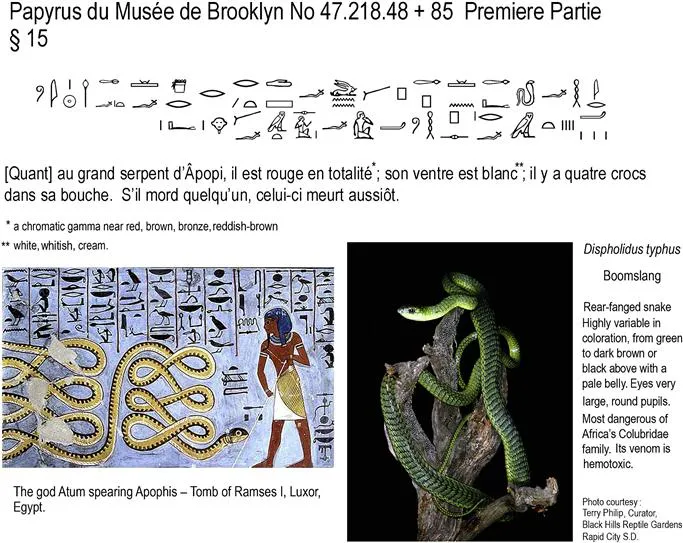

The snake identification in the Brooklyn Papyri has raised an interesting issue with the snake in §15, Apophis, as this snake features most prominently in the mythology of ancient Egypt as the personification of evil. Apophis is represented in the various royal tombs and in the Book of the Dead, with consistent morphological characteristics: a large snake with a small head, large eye, and round pupil. The body is dark on top with a distinct light underbelly. Apophis in the Brooklyn Papyri [2, p. 9] is described as a large snake, reddish brown in color, with a light underbelly, having four fangs and a lethal bite. Regarding the identification of the snake in §15, John Nunn [3, p. 185] remarks, “A positive identification would be valuable, but no Egyptian snake fits the description. The largest and most rapidly fatal snake is the Egyptian cobra.” The two large dangerous snakes currently in Egypt are the Egyptian Cobra and the Desert Black Snake [4, p. 69, 70, 87; 5, p. 155, 156, 188]. Although we agree with Nunn that “no Egyptian snake fits the description” of the snake in Brooklyn Papyri §15, it is possible that such a snake can be found in Sudan. The desertification shift occurring in Southern Egypt in the last five millennia resulted in its flora and fauna retreating to Sudan [2, p. 146; 6, p. 45]. Four large venomous snakes found today in Sudan are the Black Mamba, Puff Adder, Black Spitting Cobra, and Boomslang [5, p. 165, 194, 198, 203]. While no longer found in Egypt, the Puff Adder can be easily identified as the snake in §33 [2, p. 29]. Of these four snakes, only the Boomslang (Dyspholidus typhus in the Colubridae family) has those physical characteristics that could correspond to the snake in §15, Apophis (Figure 1.2).

1.2.2 Symptoms of Snakebite

The Brooklyn Papyri and other Egyptian texts demonstrate that the ancient Egyptians recognized the different symptoms and signs of serious snake envenomation according to their source: vipers or cobras and related snakes (elapids). An example is found in the legend of the god Ra suffering the effects of viper envenomation after having been struck by a snake [7, p. 324, 325].

Today, we understand that these clinical effects are due to the main toxic components of the specific venoms in the various snake families, predominantly hemotoxins in vipers and neurotoxins in elapids.

Viper venom causes tissue damage at the bite site and in its proximity, with changes in red blood cells, defects in coagulation, and damage to blood vessels and often to the heart, kidneys, and lungs.

Neurotoxic venoms of elapid snakes (i.e., cobras) cause lesser local tissue damage, but rapid alterations to the nervous system, secondary cardiac and respiratory...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Toxicology in Antiquity

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface to the Series and Volumes 1 and 2

- Chapter 1. Toxicology in Ancient Egypt

- Chapter 2. The Death of Cleopatra: Suicide by Snakebite or Poisoned by Her Enemies?

- Chapter 3. Mithridates of Pontus and His Universal Antidote

- Chapter 4. Theriaca Magna: The Glorious Cure-All Remedy

- Chapter 5. Nicander, Thêriaka, and Alexipharmaka: Venoms, Poisons, and Literature

- Chapter 6. Alexander the Great: A Questionable Death

- Chapter 7. Harmful Botanicals

- Chapter 8. The Case Against Socrates and His Execution

- Chapter 9. The Oracle at Delphi: The Pythia and the Pneuma, Intoxicating Gas Finds, and Hypotheses

- Chapter 10. The Ancient Gates to Hell and Their Relevance to Geogenic CO2

- Chapter 11. Lead Poisoning and the Downfall of Rome: Reality or Myth?

- Chapter 12. Poisons, Poisoners, and Poisoning in Ancient Rome