![]()

PART I

Foundations

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

On October 16, 2013, the United States Senate voted 81–18 in favor of a bipartisan agreement ending a 16-day partial government shutdown. This resulted from a partisan impasse over the continued implementation of the Affordable Care Act, alternatively referred to as Obamacare. A few months later, Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) was interviewed on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. When asked about the aftermath of the shutdown, Speaker Boehner had this to say:

Listen, I told my colleagues in July, I didn’t think shutting down the government over Obamacare [would] work because the President said I’m not going to negotiate. And so I told them in August. Probably not a good idea. Told them in early September.

So I said, do you want to fight this fight? I’ll go fight the fight with you. But it was a very predictable disaster. And so the sooner we got it over with the better. But remember the issue. The issue was, we wanted to delay Obamacare for a year because it wasn’t ready. Then we asked them to delay the individual mandate for a year. So we were fighting for the right things; I just thought tactically it was not the right way to do it.1

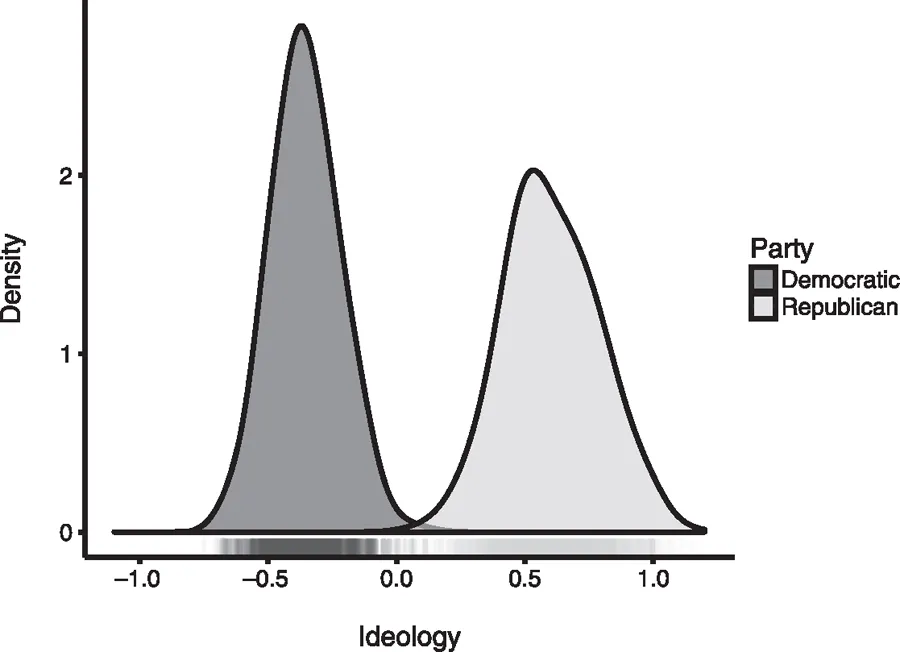

Republicans agree on policy. We know this. Figure 1.1 presents a graphical depiction of the ideologies of all members of Congress during the 104th through the 112th Congresses, as measured by Poole and Rosenthal’s (1997) DW-NOMINATE scores, which are estimates of the latent ideology of legislators generated via examination of their recorded (or roll call) votes. As the graphic shows, Republicans are clustered on the right side of the ideological scale, and Democrats are clustered on the left side, indicating significant degrees of preference similarity within parties but little to none across parties.

FIGURE 1.1. Estimates of Congressional Ideology

As the Speaker said on Leno, the caucus disagreed on tactics, even though the underlying policy preferences—to stop the implementation of the Affordable Care Act—were the same.

1.1 A Tale of Two Senators: Chuck and Roy Disagree on the Shutdown

We managed to divide ourselves on something we were unified on, over a goal that wasn’t achievable.—Senator Roy Blunt (R-MO)2

There’s been a lot of talk about the negative impact of not raising the debt limit, but there’s too little focus on the negative consequences of ignoring the $17 trillion debt. Government spending has exploded since 2008, increasing the national debt by $6 trillion. Obamacare is a drag on the economy and hurting workers’ ability to find full-time jobs. Yet the President refuses to lead for fiscal responsibility, both short and long term, even with a government shutdown. This agreement raises the debt limit with no action on the debt. It’s a missed opportunity for forcing action to limit government and increase economic opportunities.—Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA)3

On the day of the vote to end the shutdown, Republican senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Roy Blunt (R-MO) entered the chamber with identical policy goals—to defund or delay implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Yet Senator Blunt voted for the agreement to end the shutdown and Senator Grassley voted against it. Additionally, several weeks prior, Senator Blunt had voted to end debate on H.J. Res. 59, a House-passed continuing resolution to fund the government—a vote many conservative activists decried as being essentially a vote against delaying implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Senator Grassley had voted to sustain the filibuster. In a press release issued the day of the vote to end debate on H.J. Res. 59, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) claimed that “far too many Republicans joined Harry Reid in giving the Democrats the ability to fund Obamacare.”4

These votes are particularly interesting because the spatial model of voting assumes legislators vote purely on the basis of the proximity of their ideal points to the positions of the alternatives under consideration. This approach carries the assumption that the tactics and procedures on which legislators vote achieve a particular policy position with certainty, that legislators are indifferent between tactics, and that the eventual policy outcome is known a priori to all legislators. This simplification—while useful for modeling purposes and tractability—is inherently flawed, as individuals who share common policy objectives frequently debate among themselves over which tactics and procedures are preferred, and which are most likely actually to achieve mutually agreed-upon ends.

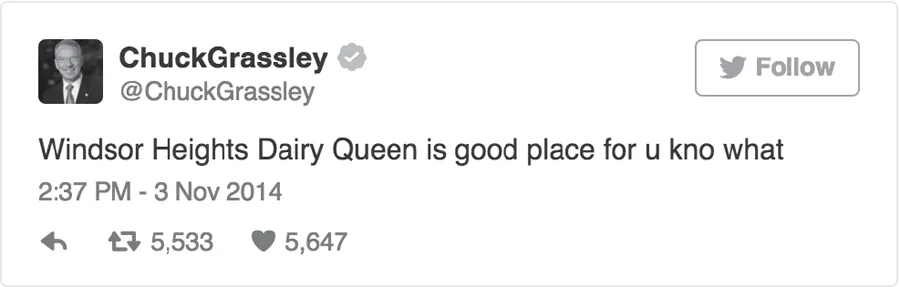

FIGURE 1.2. Senator Grassley (R-IA) Tweet Example

Given the context of the vote to end the shutdown as well as the votes that preceded it, the spatial model seems lacking. Indeed, while most of the support for continuing the shutdown came from those on the more conservative end of the spectrum, Senator Blunt is actually more conservative than Senator Grassley, as measured by their Common Space scores (Poole and Rosenthal 1997).5 However, if we look beyond their ideologies and instead at their preferences for how they conduct business, the votes might make more sense. For starters, Senator Grassley is reasonably well-known for his prolific use of Twitter (having adopted it relatively early, in November 2007, only a few months after President Barack Obama) and is notable for handling his account himself as opposed to appointing a designated staffer.6 He maintains this practice despite the occasional unclear or arguably strange tweet, an example of which is presented as Figure 1.2.7

This willingness not only to be an early adopter of a new technology (at least relative to his colleagues) but to manage his account himself—despite the occasional misstep—speaks volumes about Senator Grassley’s willingness to take risks. Senator Blunt, on the other hand, joined Twitter in 2009—over a year after Senator Grassley joined—and a “new media” director manages his more official (and less personal) Twitter account.8 In contrast to Senator Grassley, Senator Blunt’s Twitter adoption timing and his more conventional social media management style paints the picture of someone less willing to partake in risky behavior. Considered in this light, their decisions to vote differently on the agreement to end the shutdown—as well as their different cloture votes prior to the shutdown—make more sense. Senator Grassley, being less risk averse, was willing to take the riskier option of letting the shutdown occur and the debt ceiling be reached in order to force a deal on the Affordable Care Act, whereas the more risk-averse Senator Blunt—despite having the same policy goals and being more conservative than Senator Grassley—was not. If this is even remotely true, then scholars of legislative behavior—and elite behavior more generally—need to look beyond the spatial model and account for varying preferences and beliefs over tactics.

As such, we argue that legislators do not act solely upon policy positions per se but also on intermediary tactical actions that bridge individual policy preferences and legislative outcomes.9 Individuals have heterogeneous beliefs and uncertainty regarding which tactics are most likely to achieve their desired ends, and may also derive utility from how policy is produced. Accordingly, legislators use decision-theoretic methods to evaluate competing tactics. In the Blunt/Grassley example, both senators wanted to prevent implementation of the Affordable Care Act. However, they disagreed over whether the tactical mechanism—the shutdown—was the best and most appropriate means by which they could achieve their shared goal. Each senator drew upon his own preferences/beliefs pertaining to the translation from tactics to policy and came to a different decision, with one voting to continue the shutdown and the other voting to end it. Thus, the key to understanding legislative behavior is to characterize and estimate the beliefs and preferences of legislators over the tactics available to them. But how?

1.2 Traits and Elite Behavior in Institutions

This question of how to understand legislators’ behavior as a function of beliefs and preferences over tactics is ripe for exploration, as scholars of institutions have, implicitly and explicitly, acknowledged the roles played by nonpolicy traits within institutional structures. For example, congressional scholars already acknowledge that nonpolicy individual differences are often important to legislative behavior and elections. Indeed, we frequently incorporate office motivation into our models of legislative behavior, and often incorporate terms for the valence characteristics of candidates into models of elections. These terms are often discussed in terms of personal character but also in terms of leadership ability.

Within the institution of Congress itself, some theoretical models have incorporated nonpolicy qualities of individuals, including character, ability, and alternative motivations. However, there has been no systematic attempt to incorporate more broadly influential individual differences into these models. This lack of theoretical development is strange, since the classic and foundational works of American politics focused on describing individual differences in elite behavior. These works generally predate the new institutionalism of the 1980s. Indeed, a focus on personal style permeated early studies of elite behavior in Congress. Fenno’s classics Home Style: House Members in Their Districts (1978), and Congressmen in Committees (1973) are excellent examples of works that examine the individual differences that lead politicians to approach their institutional roles differently.

Additionally, the study of the presidency was, until only fairly recently, dominated by studies of leadership traits and typologies of personal leadership styles. While Barber (1972) is a prime example of this style of work, more recent works (Rubenzer and Faschingbauer 2004) across political science, psychiatry, and psychology have since continued in this research tradition. The same is true for studies of the judiciary, as the structure of judicial decision making—either one person making decisions or a small group making decisions via deliberation—has lent itself to personality-based analysis (Gibson 1981). However, in contrast to the history of model-based analysis of legislative behavior, and the more recent history for executive and bureaucratic behavior, studies of the judiciary have only very recently begun transitioning from a qualitative focus on individual differences and legalism to an institutional approach centered on modeling and policy preferences, possibly in part due to the reluctance of some to treat the courts in ideological terms.

These classics have inspired several important research agendas, but to a large extent they cannot meaningfully communicate with contemporary students of political institutions. While the classics were often qualitative studies that created interesting typologies of leadership, the dominant paradigm is quantitative and theorizes on the basis of rational choice-based models, both formal and informal. Nonetheless, a tremendous amount of accumulated qualitative knowledge exists on the influence of individual differences on elite behavior within American political institutions. Models have allowed scholars of American political institutions to clarify theories of institutional behavior, but they would gain from developing a language allowing individual differences to be comprehensively modeled.

1.2.1 Translating Individual Differences into the Language of Institutions

In this book, we seek to identify a Rosetta stone that will allow students of political institutions to begin a dialogue with the rich literature on individual differences. Ideally, this approach would comprehensively and tractably include the most important persistent individual differences into models of institutional politics. The field most dedicated to studying these individual differences is personality psychology (Borghans, Duckworth, Heckman, and Weel 2008). There are many definitions of personality, but scholars generally argue that personality consists of several interrelated components, including differences in motivations, reputations, expectations, values, interests, and attitudes, rather than a single monolithic difference (Almagor, Tellegen, and Waller 1995; Benet-Martínez and Waller 1997; McAdams 2006; McAdams and Pals 2006; Roberts and Webb 2006). Caprara and Cervone (2000) broadly describe personality as a dynamic system of structures and processes organized by individuals in order to develop a sense of personal identity. Personality, as a dynamic system, is influenced by biological and environmental factors, though personality psychologists differ greatly over the extent to which personality is biologically determined and the degree of change that is possible over time (Costa and McCrae 1997; Roberts, Robins, Trzesniewski, and Caspi 2003; Rutter 2006). Nonetheless, personality psychologists strive to develop and refine theories of personality that account for the diverse components of personality and how they influence one another (Caprara 1996). However, according to Costa and McCrae (1988) and others, only differences that stably persist can be considered elements of personality.

Persistent elements of personality are referred to as personality traits. Individual differences within this subset possess properties making them particularly well suited for incorporation into models of institutional politics. By definition, traits do not shift much in the time frame used in our models, fitting many standard assumptions made in the revealed preference paradigm about policy preferences. That said, though personality traits are distinguished through their stability, and there is evidence of consistency in trait estimates over time, there is evidence that traits shift with age (Roberts and DelVecchio 2000; Roberts, Wood, and Caspi 2008). A prominent school of thought argues that personality traits never change after adolescence (Costa and McCrae 1994; McCrae 1994; Costa and McCrae 1997; McCrae and Costa 2005). On the other hand, there is evidence that some change occurs in individuals’ personality traits at various points in the lifespan (Costa, McCrae, and Siegler 1999; Roberts et al. 2003; Roberts, Walton, and Viechtbauer 2006; Roberts, Wood, and Caspi 2008). However, even those scholars who advocate for personality shifts claim this change requires consistent environmental pressure strong enough to overcome forces for stability (Borghans et al. 2008). Within most politicians’ careers, even if traits do shift, these changes should be small in magnitude, allowing scholars to assume they are fixed in the vast majority of contexts in which political scientists are interested.

Personality trait psychologists have accumulated copious information about how personality traits capture myriad human behaviors. Moreover, they have identified trait measures with varying applications. The personality types and traits of ego control and ego resiliency identified by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) questionnaire have been applied to several workplace and career applications (Block and Block 1980; Myers, McCaulley, and Most 1985).10 Personality psychologists have also developed lists of personality traits for the purposes of diagnosing personality disorders, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and the California Personality Inventory (Gough 1985; Tellegen 2003). Yet other personality traits with negative implications for society or the polity—such as authoritarian personality, or the “dark triad” of narcissism, Machiavellianism, an...