![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Botanical Reconquista

First Glance: Making the Empire Visible

In 1790, the Spanish artist José del Pozo drew a self-portrait in Patagonia, where he had traveled as a member of the Spanish scientific expedition commanded by naval officer Alejandro Malaspina between 1789 and 1794 (fig. 1.1).1 This wash drawing is remarkable as a rare representation of eighteenth-century traveling naturalists and artists at work in the field. Pozo depicted three central figures in the foreground: himself in the center, surrounded by a Patagonian woman to the right of the image and the Guatemalan Creole naturalist Antonio Pineda to the left, literally looking over the artist’s shoulder. Behind this group Pozo sketched three human figures surrounding two pack horses, emphasizing the itinerant character of the expedition. Despite the potential discomforts and distractions of this outdoor setting, so far from the classrooms of Madrid’s San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts where Pozo had trained, the drawing shows him working with rapt concentration. He has traveled far to depict this Patagonian woman from nature, a unique opportunity to come face to face with a New World population that was little known and much mythologized at the time. Pozo placed himself to the side of the composition, in profile, in this way allowing the viewer to look straight into the woman’s eyes as the artist himself would have done to represent her frontally. By depicting not only the subject of his study but the very process of representation, Pozo transforms the viewer into a virtual traveler who can witness this American scene.2

The Malaspina expedition employed three naturalists and nine artists who, as the drawing suggests, worked closely together. This team created about a thousand drawings of various kinds intended for imperial administrators and institutions back in Madrid: botanical and zoological illustrations, city and coastal views, ethnographic portraits and scenes, and maritime scenes depicting the progress of the expedition’s two ships, Descubierta (Discovery) and Atrevida (Daring) (figs. 3.3, 3.4, 5.1).3 In addition to these visual materials that the team of naturalists and artists produced in collaboration, naval officers generated numerous coastal views, charts, and maps. The participation of so many artists in a scientific expedition and their prolific output are indicative of how eighteenth-century Spanish scientific expeditions sought to make the empire visible through observations and depictions.

This chapter discusses the ambitious program of imperial science established in the Hispanic world during the reigns of Charles III (r. 1759–88) and Charles IV (r. 1788–1808) of Spain. This scientific program included scientific expeditions, the creation of new institutions and renewal of existing ones, and the recruitment of the colonial administrative network as scientific informants. The goal was to uncover and exploit the natural riches of the Spanish empire, protecting it from incursions from European competitors and restoring it to a more prosperous state. Botany was particularly well suited to addressing Spanish concerns with utility, profit, and the search for renewed political and economic power, especially in trade with the Indies. And, drawing on a long Spanish imperial and colonial tradition, visual documents held privileged status as ways of incarnating and circulating information, helping to make the empire visible.

Natural History Expeditions in the Hispanic World, 1777–1816

In the fifty years between Charles III’s accession to the Spanish throne in 1759 and the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808, almost sixty scientific expeditions traveled through the vast Hispanic empire.4 These expeditions addressed scientific, economic, administrative, and political goals. Their varied tasks included investigating the viceroyalties’ flora and fauna; exploring imperial frontiers; charting coastlines and producing maps, particularly of lesser known or contested areas; conducting astronomical observations and measurements; and reporting on the political and administrative state of the kingdoms.5

Amid this flurry of scientific activity, botanical expeditions held a privileged position. In 1777 a royal order launched the Royal Botanical Expedition to Chile and Peru (1777–88), led by Spanish naturalists Hipólito Ruiz and José Pavón.6 The document lists the various ways in which botanical exploration would prove useful to the Spanish empire. Charles pronounced the expedition

advisable for my service and for the good of my vassals, not only to promote the progress of the physical sciences, but also to banish doubts and adulterations in matters of medicines, dyes, and other important arts; and to increase commerce; and in order that herbaria and collections of natural products be formed, describing and delineating the plants that are to be found in those fertile dominions of mine; [and] to enrich my natural history cabinet and court botanical garden.7

Thus, the expedition operated in three interrelated domains: taxonomic botany, economic botany, and collecting. The first aspect, the “progress of the physical sciences,” refers to surveying and classifying specimens according to Linnaean taxonomy, a task accomplished through the accumulation and study of specimens, written descriptions, and illustrations of American flora. The expedition also actively pursued economic botany, seeking to solve controversies regarding naturalia with medical and industrial uses and to identify valuable natural commodities. Specific goals included fostering the exploitation of cinchona, a valuable febrifuge and a Spanish monopoly; exploring whether natural commodities held in monopoly by European competitors, such as coffee, tea, pepper, cinnamon, or nutmeg, existed in the viceroyalties; and identifying potential replacements for such products. Finally, collections of objects and illustrations would enrich two recently established Madrid institutions, the Royal Botanical Garden (f. 1755) and Royal Natural History Cabinet (f. 1771), where they would not only serve as objects of scientific study but also bring prestige and renown to the royal collections.

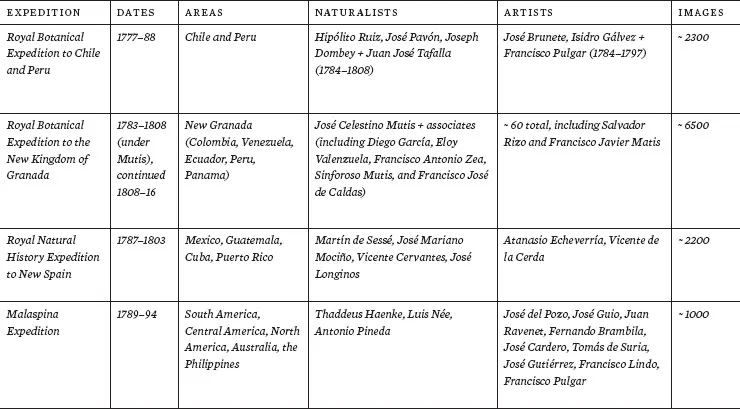

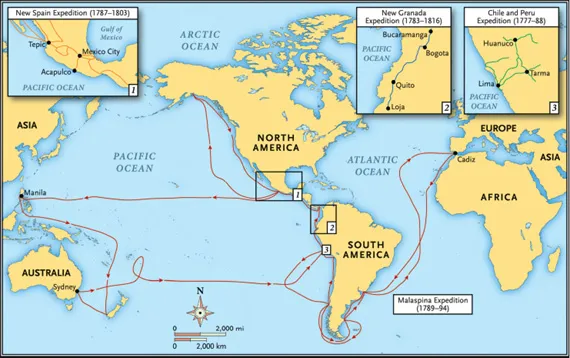

During the following twelve years, comparable orders authorized two other royal botanical expeditions, to the New Kingdom of Granada (1783–1816) under the direction of José Celestino Mutis, and to New Spain (1787–1803) led by Martín de Sessé and José Mariano Mociño.8 In addition, the naval expedition led by Alejandro Malaspina (1789–94) employed botanists who pursued these same goals. These voyages did not arise or take place independently of one another; on the contrary, they were closely connected in a complicated tangle of emulation, cooperation, and competition. As a group, they employed more than fifteen naturalists and about four times as many artists, who worked in a sustained fashion over a period of thirty years on a global mission to investigate the floras of Spain’s vast overseas territories in the Americas and the Philippines (see the table, and fig. 1.2). Their work entailed conducting and recording observations; gathering and shipping collections of seeds, plants, insects, and animals; and producing thousands of illustrations. In this way, the expeditions captured and transported imperial nature in multiple media—words, things, and images.9

This large-scale investment attests to the promise that botanical exploration held for naturalists and administrators alike, who hoped that it would prove profitable and useful to the empire. Plants, animals, and minerals provided valuable commodities for use in medicine and industry, pitting European powers against one another. This climate of international economic and political competition created opportunities for naturalists to sell their services to interested patrons. Naturalists eagerly pursued the new patronage opportunities that botanical expertise presented—particularly if they were young and could travel, or if they resided outside of Europe and served as indispensable sources of information and samples. At the time, botany was big business and big science, and botanical expertise became a highly valuable form of knowledge.10

Natural history expeditions in the Spanish empire, 1777–1816

The expeditions functioned as large-scale international collaborations that brought together European and non-European naturalists, artists, and informants. The expeditions’ members included not only Spaniards but also Frenchmen, Italians, a Bohemian, and a Tuscan, as well as Creoles and mestizos—that is, American-born people of European and of mixed European and Amerindian heritage—from Guatemala, Mexico, New Granada, and Ecuador. The international cast grows even larger if we take into account the many named and unnamed collectors, servants, aides, and informants that contributed to the expeditions through their labor and expertise—those all-important “invisible technicians” whose presence in the historical record can be limited to a brief and frustratingly inconclusive mention, if they appear at all.11 This internationalism can easily be obscured when we refer to these as “Spanish” expeditions. Imperial history sits uneasily within the tighter parameters of national history, given the mobility of individuals across geographical and cultural borders.12

The expeditions were also international in terms of the practices and networks of natural history, understood as a collective cosmopolitan project that transcended national confines. The methods and practices that these travelers followed, as well as their double pursuit of taxonomic and economic botany, were common to British and French expeditions. Naturalists throughout and beyond Europe shared methodologies and materials, engaging in a common enterprise of collective empiricism at once collaborative and competitive. Spanish and American naturalists read the same books as their colleagues from Britain, France, Northern Europe, and elsewhere. They received similar training, followed similar methods, performed similar tasks, and agreed or disagreed over systems they all knew. Naturalists often corresponded with one another, and a flurry of multimedia exchanges took place within this far-flung international community. Mutis, for example, sent letters, specimens, and images from New Granada to Madrid and other Spanish cities, to many destinations in the Americas, and also to some select European correspondents, most notably Carl Linnaeus in Sweden. He regularly received letters and materials from multiple locations and was able to amass a magnificent library with 9,000 volumes, which contained natural history works published in England, France, Holland, and Vienna, all of them sent by correspondents. He was as attentive to what happened in Uppsala, London, and Paris as in India, China, and Indonesia.13

FIGURE 1.2. Natural history expeditions in the Spanish empire, 1777–1816.

Despite their participation in global natural history, the Spanish expeditions differ in significant ways from contemporary British or French voyages. Most directly relevant to my argument about visual epistemology is their much larger visual production. Another key distinction is that for the most part the Spanish expeditions explored well-established imperial territories that went back over two centuries. Their objective was not discovery but rather rediscovery. A third noteworthy difference concerns their duration. Most Spanish expeditions extended over a much lengthier period than the voyages sponsored by other European nations. The Malaspina expedition, which lasted only five years, is the one exception—it was inspired by Captain Cook’s voyages and followed this model closely. The other expeditions, however, are measured in decades, not single digits. Ruiz and Pavón spent eleven years in Chile and Peru (1777–88). When they returned to Spain they arranged for pharmacist Juan José Tafalla and draftsman Francisco Pulgar to continue their work; these two men investigated the flora of Chile and Peru for an additional twenty-five years.14 Mutis worked in New Granada for twenty years before the botanical expedition received royal approval in 1783; he then led a large team of collaborators until his death twenty-five years later in 1808, and the expedition continued for another eight years until the independence war brought it to an end in 1816. The New Spain expedition operated for sixteen years. As a group, the Spanish expeditions represent a sustained engagement with natural history exploration at a scale unmatched anywhere else in the world at the time, often blurring the line between expedition and institution.

The expeditions’ long duration had important implications. The extended time frame allowed naturalists to examine the regions they explored in minute detail, to benefit from exchanges with a large number of local experts as they developed relationships, and to work on thorny problems for as long as necessary to solve them. This privilege was rare: the vast majority of traveling naturalists tended to have much briefer encounters with the floras and faunas they explored. The few naturalists who preceded the Spaniards in their investigations of New World flora—most notably Hans Sloane, Mark Catesby, Charles Plumier, Louis Feuillée, and Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin—spent much briefer periods in the Americas.15 Alexander von Humboldt, perhaps the best-known and most influential naturalist-traveler to the Americas in the period, zipped through much of the continent in only five years (1799–1804).16 Travelers with hastier schedules ran the risk of reaching erroneous conclusions about a species or a ph...