- 498 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Peanuts: Genetics, Processing, and Utilization (Oilseed Monograph) presents innovations in crop productivity and processing technologies that help ensure global food security and high quality peanut products. The authors cover three central themes, modern breeding methods for development of agronomic varieties in the U.S., China, West Central Africa, and India, enhanced crop protection and quality through information from the peanut genome sequence, and state-of-the-art processing and manufacturing of products in market environments driven by consumer perception, legislation, and governmental policy.

- Discusses modern breeding methods and genetically diverse resources for the development of agronomic varieties in the U.S., China, India, and West Central Africa

- Provides enhanced crop protection and quality through the application of information and genetic tools derived from analysis of the peanut genome sequence

- Includes state-of-art processing and manufacture of safe, nutritious, and flavorful food products

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Origin and Early History of the Peanut

Ray O. Hammons1, Danielle Herman2, and H. Thomas Stalker2 1USDA, ARS, Coastal Plain Station, University of Georgia, Tifton, GA, USA 2Department of Crop Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA

Abstract

The peanut, Arachis hypogaea L., is a native South American legume. Macrofossil and starch grain data show peanuts moved into the Zaña Valley in Northern Peru 8500 years ago, presumably from the eastern side of the Andes Mountains, although the hulls found there do not have similar characteristics to modern domestic peanuts. At the time of the discovery of the American and European expansion into the New World, this cultivated species was known and grown widely throughout the tropical and subtropical areas of this hemisphere. The early Spanish and Portuguese explorers found the Indians cultivating the peanut in several of the West Indian Islands, in Mexico, on the northeast and east coasts of Brazil, in the warm land of the Rio de la Plata basin (Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, extreme southwest Brazil), and extensively in Peru. From these regions the peanut was disseminated to Europe, to the coasts of Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Eventually, the peanut traveled to the colonial seaboard of the present southeastern United States, but the time and place of its introduction was not documented.

Keywords

Cultivation; Early distribution; History of peanut; ProductionOverview

The peanut, Arachis hypogaea L., is a native South American legume. Macrofossil and starch grain data show peanuts moved into the Zaña Valley in Northern Peru 8500 years ago, presumably from the eastern side of the Andes Mountains, although the hulls found there do not have similar characteristics to modern domestic peanuts (Dillehay, 2007). At the time of the discovery of the American and European expansion into the New World, this cultivated species was known and grown widely throughout the tropical and subtropical areas of this hemisphere. The early Spanish and Portuguese explorers found the Indians cultivating the peanut in several of the West Indian Islands, in Mexico, on the northeast and east coasts of Brazil, in all the warm land of the Rio de la Plata basin (Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, extreme southwest Brazil), and extensively in Peru. From these regions the peanut was disseminated to Europe, to both coasts of Africa, to Asia, and to the Pacific Islands. Eventually, peanut traveled to the colonial seaboard of the present southeastern United States (US), but the time and place of its introduction was not documented.

Discussion

Chronological History

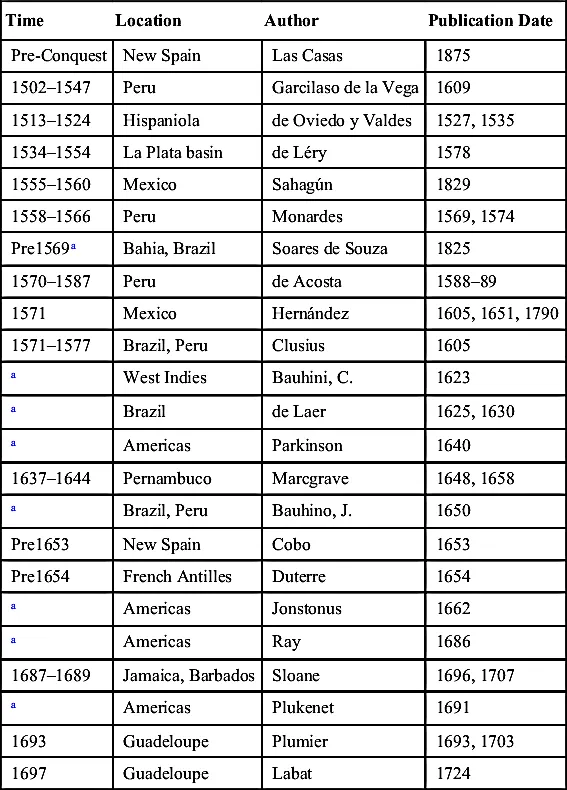

Table 1 documents the descriptions and illustrations of the peanut found in the chronicles and natural histories of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Hammons, 1973). No effort is made to discuss the extensive literature of the eighteenth century.

Before the Spanish colonization, the Incas cultivated the peanut throughout the coastal regions of Peru. In his history of the Incas, Garcilaso de la Vega (1609) describes the peanut as another vegetable which is raised under the ground, called ynchic by the Indians. He reports that the Spanish introduced the name mani from the Antilles to designate the peanut they found growing in Peru.

Table 1

The Peanut in Early Post-Colombian Historical Records: A Chronology for the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (After Hammons, 1973)

| Time | Location | Author | Publication Date |

| Pre-Conquest | New Spain | Las Casas | 1875 |

| 1502–1547 | Peru | Garcilaso de la Vega | 1609 |

| 1513–1524 | Hispaniola | de Oviedo y Valdes | 1527, 1535 |

| 1534–1554 | La Plata basin | de Léry | 1578 |

| 1555–1560 | Mexico | Sahagún | 1829 |

| 1558–1566 | Peru | Monardes | 1569, 1574 |

| Pre1569a | Bahia, Brazil | Soares de Souza | 1825 |

| 1570–1587 | Peru | de Acosta | 1588–89 |

| 1571 | Mexico | Hernández | 1605, 1651, 1790 |

| 1571–1577 | Brazil, Peru | Clusius | 1605 |

| a | West Indies | Bauhini, C. | 1623 |

| a | Brazil | de Laer | 1625, 1630 |

| a | Americas | Parkinson | 1640 |

| 1637–1644 | Pernambuco | Marcgrave | 1648, 1658 |

| a | Brazil, Peru | Bauhino, J. | 1650 |

| Pre1653 | New Spain | Cobo | 1653 |

| Pre1654 | French Antilles | Duterre | 1654 |

| a | Americas | Jonstonus | 1662 |

| a | Americas | Ray | 1686 |

| 1687–1689 | Jamaica, Barbados | Sloane | 1696, 1707 |

| a | Americas | Plukenet | 1691 |

| 1693 | Guadeloupe | Plumier | 1693, 1703 |

| 1697 | Guadeloupe | Labat | 1724 |

Bartonlomé Las Casas, who sailed in 1502 to Hispaniola (now Haiti Dominican Republic), was a missionary throughout the Spanish lands from 1510 to 1547. Although Las Casas may have been the first European to encounter the peanut, his “Apologetic History,” begun in around 1527, was not published until 1875. Concerning the peanut he wrote (Las Casas, 1909): “They had another fruit which was sown and grew beneath the soil; which were not roots but resembled the meat of the filbert nut … These had thin shells in which they grew and … (they) were dried in the manner of the sweet pea or chick pea at the time they are ready for harvest. They are called mani.” (Tr: M. Latham and R. Hammons).

The first written notice of the peanut appears to be by Captain Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, who came to Santo Domingo in 1513 and later became governor of Hispaniola and royal historiographer of the Indies. In 1525 he sent Charles V his Sumario Historia, printed in Toledo two years later (Oviedo, 1527), and in 1535 began publishing his Historia General de las Indias.

Oviedo first published the common Amerindian name mani for the peanut; the name is still used in Cuba and Spanish South America. In Chapter V, he writes (Oviedo, 1535) “Concerning the mani, which is another fruit and ordinary food which the Indians have on Hispaniola and other islands of the Indies: Another fruit which the Indians have on Hispaniola is called mani. They sow it and harvest it. It is a very common crop in their gardens and fields. It is about the size of a pine nut with the shell. They consider it a healthy food … Its consumption among the Indians is very common. It is abundant on this and other islands.” (Tr: M. Latham and R. Hammons).

A later edition published in 1851 states that the mani is “sown and grows underground, which upon pulling by the branches it is uprooted and on the runners there are found such fruit located inside pods as in chickpeas, … which are very tasty when eaten raw or roasted.” (Tr: M. Latham and R. Hammons). This statement does not appear in the earlier edition (Oviedo, 1527).

Although South America is the unquestioned place of original cultivation, it is significant that this earliest publication documents the wide distribution of this important crop plant that had occurred before the discovery of America.

Ulrich Schmidt, historian of the Spanish conquests of the Rio de la Plata basin, 1534 to 1555, frequently mentions the peanut (manduiss, mandubi) as an important plant in these warm lands. A German mercenary, Schmidt (1567) encountered the peanut as early as 1542 when his expedition up the Paraguay from Asunción met Surucusis Indians who had “maize and mandioca and also other roots, such as mandi (peanut) which resembles filberts.” (Tr: M. Latham and R. Hammons).

The peanut was described unmistakably be Jean de Léry, a Calvinist missionary with the Huguenot colony founded in 1555 on an island in Rio de Janeiro bay (de Léry, 1578): “The savages also have fruits called manobi. They grow in the soil like truffles connected one to the other by fine filaments. The pod has a seed the size of hazelnut and a similar taste; it is gray brown and the hull is the hardness of a pea. Although I have eaten this fruit many times, I cannot say whether the plant has leaves or seeds …” (Tr: T.B. Stewart).

The first purposeful introduction of the peanut into Europe went unrecorded. Useful and exotic American plants were commonly collected and introduced into Europe from the time of Columbus’ first voyage. Therefore, it ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Series Pages

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Origin and Early History of the Peanut

- Chapter 2. Biology, Speciation, and Utilization of Peanut Species

- Chapter 3. Global Resources of Genetic Diversity in Peanut

- Chapter 4. Recent Advances in Peanut Breeding and Genetics

- Chapter 5. The Peanut Genome: The History of the Consortium and the Structure of the Genome of Cultivated Peanut and Its Diploid Ancestors

- Chapter 6. Annotation of Trait Loci on Integrated Genetic Maps of Arachis Species

- Chapter 7. Application of Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Metabolomic Technologies in Arachis Species

- Chapter 8. PeanutBase and Other Bioinformatic Resources for Peanut

- Chapter 9. Overview of the Peanut Industry Supply Chain

- Chapter 10. An Overview of World Peanut Markets

- Chapter 11. Peanut Composition, Flavor and Nutrition

- Chapter 12. Mycotoxins and Product Safety

- Chapter 13. New Therapeutic Strategies for Peanut-Related Allergy

- Chapter 14. Raw Peanut Processing

- Chapter 15. Processing and Food Uses of Peanut Oil and Protein

- Chapter 16. Manufacturing Foods with Peanut Ingredients

- Chapter 17. The Role of Peanuts in Global Food Security

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Peanuts by Thomas Stalker,Richard F. Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Agribusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.