1.2.1 The Process of Recognition

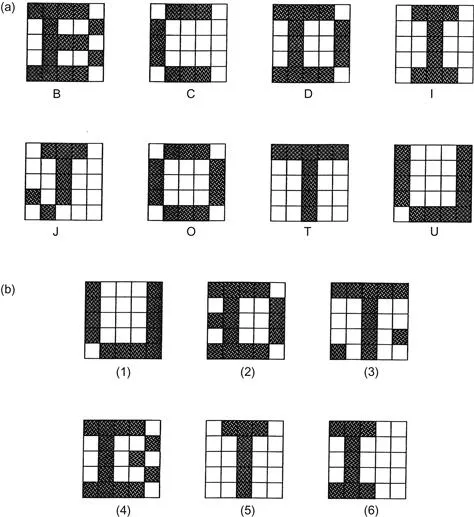

This section illustrates the intrinsic difficulties of implementing machine vision, starting with an extremely simple example—that of character recognition. Consider the set of patterns shown in Fig. 1.1(a). Each pattern can be considered as a set of 25 bits of information, together with an associated class indicating its interpretation. In each case imagine a computer learning the patterns and their classes by rote. Then any new pattern may be classified (or “recognized”) by comparing it with this previously learnt “training set,” and assigning it to the class of the nearest pattern in the training set. Clearly, test pattern (1) (Fig. 1.1(b)) will be allotted to class U on this basis. Chapter 24 shows that this method is a simple form of the nearest-neighbor approach to pattern recognition.

Figure 1.1 Some simple 25-bit patterns and their recognition classes used to illustrate some of the basic problems of recognition: (a) training set patterns (for which the known classes are indicated); (b) test patterns.

The scheme outlined above seems straightforward and is indeed highly effective, even being able to cope with situations where distortions of the test patterns occur or where noise is present: this is illustrated by test patterns (2) and (3). However, this approach is not always foolproof. First, there are situations where distortions or noise are excessive, so errors of interpretation arise. Second, there are situations where patterns are not badly distorted or subject to obvious noise, yet are misinterpreted: this seems much more serious, since it indicates an unexpected limitation of the technique rather than a reasonable result of noise or distortion. In particular, these problems arise where the test pattern is displaced or misorientated relative to the appropriate training set pattern, as with test pattern (6).

As will be seen in

Chapter 24, there is a powerful principle that indicates why the unlikely limitation given above can arise: it is simply that there are

insufficient training set patterns, and that those that are present are

insufficiently representative of what will arise in practical situations. Unfortunately, this presents a major difficulty, since providing enough training set patterns incurs a serious storage problem, and an even more serious search problem when patterns are tested. Furthermore, it is easy to see that these problems are exacerbated as patterns become larger and more real (obviously, the examples of

Fig. 1.1 are far from having enough resolution even to display normal type-fonts). In fact, a combinatorial explosion

1 takes place. Forgetting for the moment that the patterns of

Fig. 1.1 have familiar shapes, let us temporarily regard them as random bit patterns. Now the number of bits in these

N×

N patterns is

N2, and the number of possible patterns of this size is

: even in a case where

N=20, remembering all these patterns and their interpretations would be impossible on any practical machine, and searching systematically through them would take impracticably long (involving times of the order of the age of the universe). Thus, it is not only impracticable to consider such brute-force means of solving the recognition problem, it is effectively also impossible theoretically. These considerations show that other means are required to tackle the problem.

1.2.2 Tackling the Recognition Problem

An obvious means of tackling the recognition problem is to standardize the images in some way. Clearly, normalizing the position and orientation of any 2-D picture object would help considerably: indeed this would reduce the number of degrees of freedom by three. Methods for achieving this involve centralizing the objects—arranging their centroids at the center of the normalized image—and making their major axes (deduced by moment calculations, for example) vertical or horizontal. Next, we can make use of the order that is known to be present in the image—and here it may be noted that very few patterns of real interest are indistinguishable from random dot patterns. This approach can be taken further: if patterns are to be nonrandom, isolated noise points may be eliminated. Ultimately, all these methods help by making the test pattern closer to a restricted set of training set patterns (although care must also be taken to process the training set patterns initially so that they are representative of the processed test patterns).

It is useful to consider character recognition further. Here, we can make additional use of what is known about the structure of characters—namely, that they consist of limbs of roughly constant width. In that case the width carries no useful information, so the patterns can be thinned to stick figures (called skeletons—see Chapter 9); then, hopefully, there is an even greater chance that the test patterns will be similar to appropriate training set patterns (Fig. 1.2). This process can be regarded as another instance of reducing the number of degrees of freedom in the image, and hence of helping to minimize the combinatorial explosion—or, from a practical point of view, to minimize the size of the training set necessary for effective recognition.

Figure 1.2 Use of thinning to regularize character shapes. Here, character shapes of different limb widths—or even varying limb widths—are reduced to stick figures or skeletons. Thus, irrelevant information is removed and at the same time recognition is facilitated.

Next, consider a rather different way of looking at the problem. Recognition is necessarily a problem of discrimination—i.e. of discriminating between patterns of different classes. However, in practice, considering the natural variation of patterns, including the effects of noise and distortions (or even the effects of breakages or occlusions), there is also a problem of generalizing over patterns of the same class. In practical problems there is a tension between the need to discriminate and the need to generalize. Nor is this a fixed situation. Even for the character recognition task, some classes are so close to others (n’s and h’s will be similar) that less generalization is possible than in other cases. On the other hand, extreme forms of generalization arise when, e.g., an A is to be recognized as an A whether it is a capital or small letter, or in italic, bold, suffix or other form of font—even if it is handwritten. The variability is determined largely by the training set initially provided. What we emphasize here, however, is that generalization is as necessary a prerequisite to successful recognition as is discrimination.

At this point it is worth considering more carefully the means whereby generalization was achieved in the examples cited above. First, objects were positioned and orientated appropriately; second, they were cleaned of noise spots; and third, they were thinned to skeleton figures (although the latter process is relevant only for certain tasks such as character recognition). In the last case we are generalizing over characters drawn with all possible limb widths, width being an irrelevant degree of freedom for this type of recognition task. Note that we could have generalized the characters further by normalizing their size and saving another degree of freedom. The common feature of all these processes is that they aim to give the characters a high level of standardization against known types of variability before finally attempting to recognize them.

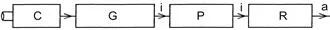

The standardization (or generalization) processes outlined above are all realized by image processing, i.e. the conversion of one image into another by suitable means. The result is a two-stage recognition scheme: first, images are converted into more amenable forms containing the same numbers of bits of data; and second, they are classified, with the result that their data content is reduced to very few bits (Fig. 1.3). In fact, recognition is a process of data abstraction, the final data being abstract and totally unlike the original data. Thus, we must imagine a letter A starting as an array of perhaps 20 bits×20 bits arranged in the form of an A, and then ending as the 7 bits in an ASCII representation of an A, namely 1000001 (which is essentially a random bit pattern bearing no resemblance to an A).

Figure 1.3 The two-stage recognition paradigm: C, input from camera; G, grab image (digitize and store); P, preprocess; R, recognize (i, image data; a, abstract data). The classical paradigm for object recognition is that of (i) preprocessing (image processing) to suppress noise or other artifacts and to regularize the image data, and (ii) applying a process of abstract (often statistical) pattern recognition to extract the very few bits required to classify the object.

The last paragraph reflects to a large extent the history of image analysis. Early on, a good proportion of the image analysis problems being tackled were envisaged as consisting of an image “preprocessing” task carried out by image processing techniques, followed by a recognition task undertaken by statistical pattern recognition methods (Chapter 24). These two topics—image processing and statistical pattern recognition—consumed much research effort and effectively dominated the subject of image analysis, while “intermediate-level” approaches such as the Hough transform were, for the time, slower to develop. One of the aims of this book is to ensure that such intermediate-level processing techniques...