eBook - ePub

Cognitive Neuropsychology

A Clinical Introduction

This is a test

- 428 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is unique in that it gives equal weight to the psychological and neurological approaches to the study of cognitive deficits in patients with brain lesions. The result is a balanced and comprehensive analysis of cognitive skills and abilities that departs from the more usual syndrome approach favored by neurologists and the anti-localizationist perspective of cognitive psychologists.Gives an introductory account of the core subject matter of cognitive neuropsychology**Provides a comprehensive review of the major deficits of human cognitive function**Offers the expertise of two scientists who are also practicing neuropsychologists

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cognitive Neuropsychology by Rosaleen A. McCarthy,Elizabeth K. Warrington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Surgery & Surgical Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Surgery & Surgical Medicine1

Introduction to Cognitive Neuropsychology

Publisher Summary

This chapter presents an introduction to cognitive neuropsychology. The term cognitive neuropsychology is applied to the analysis of those handicaps in human cognitive function that result from brain injury. Cognitive neuropsychology is essentially interdisciplinary, drawing both on neurology and on cognitive psychology for insights into the cerebral organization of cognitive skills and abilities. Cognitive function is the ability to use and integrate basic capacities such as perception, language, actions, memory, and thought. The focus of clinical cognitive neuropsychology is on the many different types of highly selective impairments of cognitive function that are observed in individual patients following brain damage. The functional analysis of patients with selective deficits provides a very clear window through which one can observe the organization and procedures of normal cognition. Clinical cognitive neuropsychology has been successful in demonstrating a large number of dissociations between the subcomponents of cognitive skills. This enables to conclude that such components are dependent on distinct neural systems.

Introduction

Damage to the brain often has tragic consequences for the individual. It can affect those basic skills and abilities which are so necessary for normal everyday life and which are largely taken for granted. The rather hybrid term cognitive neuropsychology is applied to the analysis of those handicaps in human cognitive function which result from brain injury. Cognitive neuropsychology is essentially interdisciplinary, drawing both on neurology and on cognitive psychology for insights into the cerebral organisation of cognitive skills and abilities. By cognitive function is meant the ability to use and integrate basic capacities such as perception, language, actions, memory, and thought. The focus of clinical cognitive neuropsychology is on the many different types of highly selective impairments of cognitive function that are observed in individual patients following brain damage. The functional analysis of patients with selective deficits provides a very clear window through which one can observe the organisation and procedures of normal cognition. No account of “how the brain works” would even approach completeness without this level of analysis.

Consideration of cognitive impairments in people with brain damage has a long tradition in clinical medicine. However, as a coherent domain of investigation it has a relatively short history. The description and discussion of cognitive deficits following brain injury dates back to the earliest written records. For example, there is mention of specific language loss in the Edwin Smith papyrus of 3500 B.C., and selective impairments in face recognition and letter recognition were noted by Roman physicians. Few advances were made over the following 2000 years. Despite discovering the orbits of the planets, the circulation of the blood, and the laws of mechanics, the “seat of the mind” had only moved from the liver to the pineal gland.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century a number of patterns of deficit had been described and were accepted as being due to disease of the brain itself. In the early nineteenth century there were significant advances in medicine, anatomy, and physiology which provided the basis for a more adequate analysis of the sequelae of brain injury. In their first investigations the nineteenth-century researchers placed considerable emphasis on the localisation of damage which gave rise to impaired function. This approach led to a number of insights and arguably led to the development of clinical neurology as an independent specialty. Subsequently the quest for localisation led to a realisation of the complexities of cognitive function. It was recognised that abilities such as language were composed of a number of distinct processing components, each of which could break down independently of the others. This analytic approach to patterns of breakdown forms the basis of much contemporary cognitive neuropsychology. The background to both of these issues and their contemporary relevance will be considered in the following two sections. First, the evidence for localisation and lateralisation of function in the human brain will be considered. Second, the evidence for dissociation of function and the basic methodological approaches of contemporary neuropsychology will be introduced.

Localisation and Lateralisation of Function

Historical Background

In the early years of the nineteenth century the phrenologists Gall & Spurzheim (1809) speculated that the convoluted surface of the brain reflected the juxtaposition of a large number of discrete cerebral organs. Each organ was thought to subserve a particular psychological faculty (or in more contemporary terms, function). Individual differences in endowment for a specific faculty would result in different degrees of development of particular convolutions of the brain. By analogy with muscular development, they suggested that endowment with mental muscles would result in an increase in the size of cerebral organs. They further speculated that this endowment would be reflected in bulges on the skull. In support of their hypothesis they produced evidence from anthropological studies of races with supposed differences in intellectual endowment, and clinical post-mortem evidence from brain-injured individuals. One of their speculations, that the language faculty might be located in the anterior sectors of the brain, was tentatively supported by post-mortem evidence. This was corroborated in independent clinical studies conducted by the eminent French physician Bouillaud (cited by Benton, 1984). However other workers reported conflicting evidence of patients whose language abilities were preserved despite damage to this part of the brain (e.g., Andral, 1834, cited by Benton, 1964).

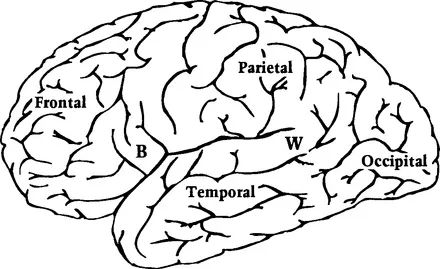

In 1861, the anthropologist and physician Paul Broca reported the case of a patient who had lost the ability to utter a single word, but who had retained his ability to understand what was said to him. The patient, a Monsieur LeBorgne, was a long-term resident in an institution who had been nicknamed “Tan” by the staff because this was the only sound he ever uttered. Despite having no meaningful speech, “Tan” (although reportedly a difficult patient) was able to cooperate with staff and to assist in the care of other inmates. Broca argued that the patient’s disorder was not one which affected the muscles which were necessary for speech, because he was able to eat and drink. The patient appeared to have a specific impairment of language. Broca suggested that the patient’s disease had damaged a specific centre in the brain which was responsible for mediating articulate language, a deficit he termed “aphemie.” In fact, the area of tissue loss or lesion in Tan was quite extensive, spreading from the frontal to the temporal lobes of the brain. Such large areas of damage would appear to pose considerable, if not intractable, problems for precise localisation. However, Broca drew on his clinical knowledge to infer the likely sequence of events which had led to the loss of language. On the basis of the progression of Tan’s difficulties, Broca argued that the onset of language disturbance was attributable to damage in a critical and restricted area, namely the third frontal convolution of the left hemisphere. This part of the brain is still termed “Broca’s area” in recognition of his pioneering attempts to localise and lateralise the site of damage responsible for disrupting speech (see Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Lateral surface of the left hemisphere showing the four major lobes. B, Broca’s area; W, Wernicke’s area.

Karl Wernicke (1874) described patients with the opposite pattern of speech difficulty to Broca’s cases—they could speak fluently, but they were unable to understand what was said to them. The patients’ speech, though fluent, was by no means normal, indeed it was virtually unintelligible. They used words inappropriately and made errors in pronunciation which reflected the wrong choice of word sounds. These errors often resulted in words which were not part of the language, an error termed a neologism (literally, a “new word”). One patient died, and when her brain was studied at post-mortem she was found to have a lesion in the left temporal lobe, near to primary auditory cortex. However, the damage was not in the primary auditory cortex itself, but slightly more posterior, extending from the first temporal convolution into the parietal lobe (see Fig. 1.1).

Broca had also noted that damage to the left hemisphere appeared to be critical for language impairment. His observations were confirmed by other researchers and appeared to be valid even when the pattern of language deficit was not identical to that described in the original cases. The idea that the left hemisphere might play a special role in language function became widely accepted. This hypothesis has stood the test of time. Post-mortem studies of the brains of patients who had shown language disturbances in life indicated that damage to the left hemisphere was usually critical. This gave rise to the view that the left hemisphere was the “dominant” or leading side of the brain in most people. It is now universally accepted that the human brain has an asymmetric organisation of function. Language abilities are compromised by damage to the left hemisphere in the vast majority of people and appear to be unaffected by damage to the right side.

A strong emphasis on the lateralisation of language, rather than on the organisation of other cognitive skills, has been characteristic of many neurological and neuropsychological studies of patients. It is easy to understand why this has happened. Language deficits are obvious and a cause of considerable concern, making them somewhat easier to detect and investigate than other types of disorder. This should not blind one to the fact that damage to the right hemisphere of the brain may also have considerable effects on other types of cognitive function. The first to recognise that the right hemisphere might have specialised functions of its own was the English neurologist Hughlings Jackson (1876). On the basis of his clinical observations of a single patient he argued that whilst the left hemisphere might be important in language, the right hemisphere was critical in “visuoperceptual” abilities. The idea that the right hemisphere might be “dominant” for some types of ability was not followed up in any great detail at the time. The prevailing viewpoint was that the cerebral hemispheres existed in a “dominance” relationship with the left hemisphere being “in charge” in most people. It is only since the 1940s that systematic investigations of perceptual and spatial abilities have been conducted in patients with unilateral lesions. The results of these investigations have supported Jackson’s original observations. It is now universally recognised that the two cerebral hemispheres have complementary, but very different, specialisations. The term cerebral dominance still continues in modern usage, however, it now has a much more restricted meaning, namely “dominance for language.”

Individual Differences?

Broca’s view that the left hemisphere was necessarily dominant for language in all individuals was challenged by other neurologists. They argued that the cerebral organisation of speech would be directly related to hand preference (e.g., Wernicke, 1874). It was suggested that writing was intimately linked with spoken language and could even be considered as “parasitic” upon it and making use of the same brain centres. It would therefore be eminently reasonable if language and writing were organised in close proximity in the brain. Since control over motor function is primarily organised in a contralateral manner (with the left hemisphere controlling the movement of the right hand and the right hemispher...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction to Cognitive Neuropsychology

- Chapter 2: Object Recognition

- Chapter 3: Face Recognition

- Chapter 4: Spatial Perception

- Chapter 5: Voluntary Action

- Chapter 6: Auditory Word Comprehension

- Chapter 7: Word Retrieval

- Chapter 8: Sentence Processing

- Chapter 9: Speech Production

- Chapter 10: Reading

- Chapter 11: Spelling and Writing

- Chapter 12: Calculation

- Chapter 13: Short-Term Memory

- Chapter 14: Autobiographical Memory

- Chapter 15: Material-Specific Memory

- Chapter 16: Problem Solving

- Chapter 17: Conclusion

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index