![]()

Chapter 1

The Semantic Environment of Science

If it dies, it’s biology, if it blows up, it’s chemistry, if it doesn’t work, it’s physics.

—John Wilkes, as quoted from graffiti on a bathroom wall.

During your work with the sciences in graduate school and in your subsequent career, you find that a great percentage of your time is spent writing papers and making presentations. Scientific communication is essential for helping us use and take care of this earth. To keep ideas alive, researchers who discover the wonders of science must tell someone about their findings in clear, complete, and concise terms. To add to the pool of scientific knowledge, research scientists must synthesize other available information with what they discover. If any scientist uses poorly chosen words, omits important points, or fails to understand a given audience, messages can become unclear or misinterpreted, and the progress of science suffers.

Before we get into a discussion of scientific papers and presentations, let’s be sure we are not harboring a common misconception about scientists. When one utters the word “scientist,” for many people the image that comes to mind is the research scientist exploring in a laboratory or the field for new discoveries in science. Certainly that person is a scientist, but think beyond that image. Careers for scientists also include many things besides research. There are practitioners who apply the scientific discoveries, consultants who advise nonscientists, the science educator who teaches science students, journalists who write about science, the science librarian or museum curate who oversees a collection of scientific materials, the sales representative who demonstrates scientific products, the science lobbyist whose job is to explain the needs of science to politicians, the horticulturalist who tends a botanical garden, and numerous other specialists.

Not all these people may have degrees in science or consider themselves scientists, but all must deal with scientific communication. Some may have doctoral degrees, some masters, some bachelors, and some may not have science degrees but have acquired enough science background to write or speak about science. They need to communicate with each other, with clientele, with students, with the general public, or with their particular audiences. The material in the following chapters is for all who find that communication about science is primary to their careers. At some points, I concentrate on the communication specific to the research scientist, the science writer, or another audience, but almost every chapter contains fundamentals of communication common to all of us.

No special talent is required nor is magic involved in clear scientific communication. It is simply a skill developed in semantics, or in exchanging meanings with words and other symbols, within a social and scientific environment. To be successful, meanings associated with those symbols must be nearly the same for both the sender and the receiver. But either the author or the audience can manipulate meanings, and being human, both probably will. Communication is the vehicle that carries information and progress in a culture, but it also carries disputes, misinformation, and disruption of progress. Generation gaps, wars, and prejudices result, at least in part, from something communicated or not communicated. On the other hand, bridges across generation gaps, peace, and understandings as well as fantastic discoveries in the sciences are also results of communication. In scientific communication, be ever wary of the human elements and communicate as concisely, conventionally, and clearly as you can with your audience in mind.

Writing or speaking about scientific research is no more difficult than other things you do. It is rather like building a house. If you have the materials you need and the know-how to put them together, it is just a matter of hard work. The materials come from your own study and research. Any attempt to communicate in science is fruitless without quality material or content. Once ideas and data are available, you put them together with the basic skills of scientific writing or speaking. The hard work is up to you.

In any sort of work, you must learn the names of the tools you use or how to operate the instruments in the manufacturing plant, the lab, the construction site, the field, or the office. You must learn what care has to be taken with equipment and with data, or else you should not be working in science (Figure 1.1). Whether it is an ax or an autoclave, equipment can be dangerous, and so can words. Writing or speaking, like chemistry or biology, requires cautious, skillful work with the tools available, and understanding of the content and premises on which messages are based.

Figure 1.1 Learn to take care of science equipment and data, or you should not be working in science.

(Cartoon from Andrew Toos [July 1, 1992]. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Used with author’s permission.)

But more so than constructing a house or carrying out scientific experimentation, communication contains much of the human element and is far more subjective than science and less reliant on empirical data. Thus, to work with communication, you have to recognize that it emerges from the individual human into a social context where it can become either clarified into meaning or polluted into confusion. That means that no formula exists for communication, and what you say or write is modified and tempered by your own personality and belief. Its reception depends on the audience and the other elements in the semantic environment in which you deliver the message. The major objective is to get whatever the speaker or writer intends or means to an audience with the same interpretation or meaning. That is what semantics is all about—the relationship of meaning to words, physical expressions, and other symbols used to communicate.

1.1 The Semantic Environment

I use the term “semantic environment” frequently in this book. I picked it up from Neil Postman in his Crazy Talk, Stupid Talk (1976), a book I recommend that every educated individual read. Unfortunately, it is out of print, but if you cannot discover a used copy, read another of Postman’s books. Any of them will teach you more about language than I ever can. As I use the term semantic environment, which Postman suggests originated with George Herbert Mead, I am likely to add my own flavor to make it a semantic ecosystem even more ecological and applicable to a discussion of the environment in which the language of science is written and spoken. At any rate, it is one of those tools that I use here to try to provide you with suggestions on how better to communicate in science; therefore, let me expound on it a bit more from my point of view.

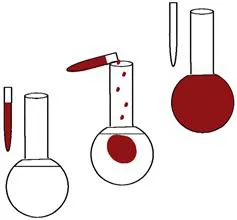

The concept of the semantic environment is what makes many of us frustrated when a statement is taken out of context. Again, I agree with Postman in that the environment or situation in which words are spoken is essential to the meaning of those words, and any element in that environment can alter a meaning. I like his analogy of pouring a drop of red ink into a beaker of water with the result that all the water in that beaker is now tinted with red (Postman, 1976) (Figure 1.2). Let’s take that analogy outside the lab to a biological ecosystem. Every organism in that ecosystem is influenced by every other organism as well as all the other chemical and physical matter in that environment. The efficacy of the organism relative to its vigor and proliferation depends on the extent to which it can thrive in that environment. Impositions on the environment can inhibit or aggressively proliferate invasive species within the ecosystem. The same context can describe your communication efforts; intended meanings can be destroyed or inhibited, and false meanings can proliferate.

Figure 1.2 Unwanted elements in the semantic environment can color an entire communication effort.

The success of your communication will depend on how well you respond to the multitude of elements in the semantic environment. For example, suppose you are to make a presentation at a meeting of scientists familiar with your field. First and foremost, the environment is scientific and carries the semantic elements of a physical setting, tone, attitudes, passions, atmosphere, and purposes of science as clearly distinguished from the situations Postman describes for the semantic environments of such things as religion, business, war, or lovemaking. As he suggests in Crazy Talk, Stupid Talk (1976), “A semantic environment includes, first of all, people; second, their purpose; third, the general rules of discourse by which such purposes are usually achieved; and fourth, the particular talk actually being used in the situation.” However, the semantic environment for your speaking situation or setting is also made up of a plethora of other smaller influences, including the size of the room, the temperature in the room, how many people are in your audience, who they are, what is in the mind of each, how much you and your audience know, how well prepared you are, and what kind of equipment or images you have for displaying visual aids, as well as the words or other symbols you choose to express yourself and what arrangement and with what tone the words come from your mouth or your keyboard. Of course, these are just a few of the multitude of influences in your semantic ecosystem, but the extent to which you can successfully use the influences that will support you and modify or resist those that deter your efforts is the extent to which you will be successful.

Maybe some of your success will depend on your turning the thermostat down a bit so that the audience is not sweltering, or shutting the door so that the noise pollution from outside does not enter the environment. A noisy late comer into the room may color the waters like the red ink, but you may be able to clear the medium by attracting audience attention back to you and your message. The semantic environment can be totally destroyed if the late comer yells, “Fire, the building is burning down. Get out.” You need not try to preserve the environment at that point, but simply direct the audience to the nearest exit and get there yourself. Except for such extraordinary disturbances, you have a great deal of control over the semantic environment, and with you as the central focus in the room, you can preserve the environment or destroy it yourself with the way you handle the various elements. What I would like to do with this book is to help you avoid destruction and to go beyond the simple preservation of that environment to success of your communication efforts throughout your career.

For this communicative organism, which is you, to survive and succeed in this semantic ecosystem depends on your understanding of the environment and your practicing good communication skills. If you do not want to be the spindly little weed among the giant redwoods of science, develop your communication skills as well as your scientific expertise. Developing communication skills requires a combination of mental and physical activity. Like any such activity, it requires regular exercise or practice to move toward perfection. With swimming, you cannot simply let someone tell you how, follow those instructions, and win a national title the first time you swim. The same is true with writing or speaking; only with continual practice can you develop and maintain the skills you need. Once you feel comfortable with those skills, you may even enjoy writing and speaking to an audience. At least you will be a healthy organism among your peers in this semantic world of science.

1.2 Basic Semantic Elements in Communication

You have been in school for many years; you know how to talk and write. You may or may not have had much of the needed practice in scientific writing, but you probably have had all the grammar and rhetoric courses you want. Do not disparage those courses. Basic instruction in the use of language is a good foundation for writing and speaking as long as you do not let that instruction inhibit your communication. Sloppy grammar, punctuation, and spelling can be highly distracting to a scientific message. But this text does not presume to instruct you on points of grammar and basic composition but, rather, on giving clear meaning to content and achieving your purpose in scientific communication with producing, reviewing, evaluating, and revising and disseminating papers and presentations. Those tasks can be easier as you define your purpose in communicating and develop guidelines that will work for you.

Any communication, and especially information exchange between scientists, is a matter of asking and answering questions. In scientific communication, asking the questions is the foundation for discovery; providing answers to your colleagues and to future generations adds knowledge to knowledge and keeps scientific progress alive and well. From “How are you?” or “What’s happening?” to “Does a virus or a bacterium cause the disease?” or “How great is the threat of global warming?” the questions form the foundation for communication. Questions are in the minds of any audience, and answering a question even before it is asked often averts many problems. If someone did not wonder about answers, science would be in real trouble. As you consider a paper or a speech for your fellow scientists, try to determine what questions are in their minds and yours and which ones you can and should answer.

All forms of scientific communications have a great deal in common but differ with the semantic environment. Variations in content and organization are imposed by the questions from different audiences and the answers you give. An audience of sixth graders will not ask the same questions that scientists in your discipline will ask, but you can cover the same subject for both groups. In communicating about your work as a scientist, content and organization are clearly influenced by scientific methods of inquiry and reflect recognition of a problem, observation, formulation of a hypothesis, experimentation, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. Notice that each of these steps poses a question that your research and then your communication seek to answer. What is the problem? What do you observe about it? What do you hypothesize? How do you experiment or explore for a solution? What data will you collect and how will you test it? What conclusions can be drawn? The content of your scientific paper will involve some or all of these questions no matter who is in the audience, and the organization of your communication will be based on a logical progression of answers.

Another major influence on organization and content is the use of conventional techniques in scientific communication. An audience can understand you if you use familiar communication devices they understand and expect. For example, most organization in scientific communication, whether it is for journal articles, laboratory reports, or seminar presentations, uses the IMRAD format. The acronym IMRAD stands for Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. For journal manuscripts, Silyn-Roberts (2000) adds an A to mean abstract so that the acronym becomes AIMRAD. These sections are the conventional or the expected order for most scientific papers. A few journals alter this formula and present results and discussion before methods. They are simply answering the question “What did you find out?” before “How did you find that solution?” That organization does not negate the convention; it just asks the questions in a different order. The IMRAD format is a common example of what is conventional or what the reader or listener expects.

Much of the expected we do without realizing we are following conventions. For example, in English the order we give to words within sentences is generally the subject first followed by the verb and then its object. Notice that the first sentence of this paragraph does not follow that pattern. As a result, the sentence sounds a little strange, and it would perhaps be a better one if the order were conventional. Except for trying to call attention to a sentence or to emphasize a certain point, you should give the reader the expected. A major purpose in this text is to outline what is conventional for the forms of scientific communications. By no means do I discourage creative modifications to those conventions, but be sure the unexpected carries the audience along with it without distraction from your purpose.

Recognizing the semantics of science and the situation in which you communicate is up to you. In addition to the questions from a given audience and the conventions that have evolved in language, your success depends on knowing who that audience is, knowing your subject and purpose, and recognizing your own abilities and convictions. These are essential influences in the semantic environment of both written and spoken communication. You must be alert to these and the other elements of the semantic environment in which you communicate, and interact with whatever supports your communication while learning to resist or tolerate any pollution that enters the ecosystem. As you grow in your career as a scientist, periodically remind yourself about the fundamentals of your science and about the fundamentals of successful communication. Visualize your audience and consider your subject and your purpose for communicating. What questions will that audience ask and how can you best answer them? What media will best convey your message? Finally, every individual communicates differently; you need to think about yourself and your own capabilities.

To merge yourself with other elements of the semantic environment, think first of your audience. They are half the communication and most important to the interpretation and understanding of your scientific message. However hard you try to send a clear message, the completed com...