- 944 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

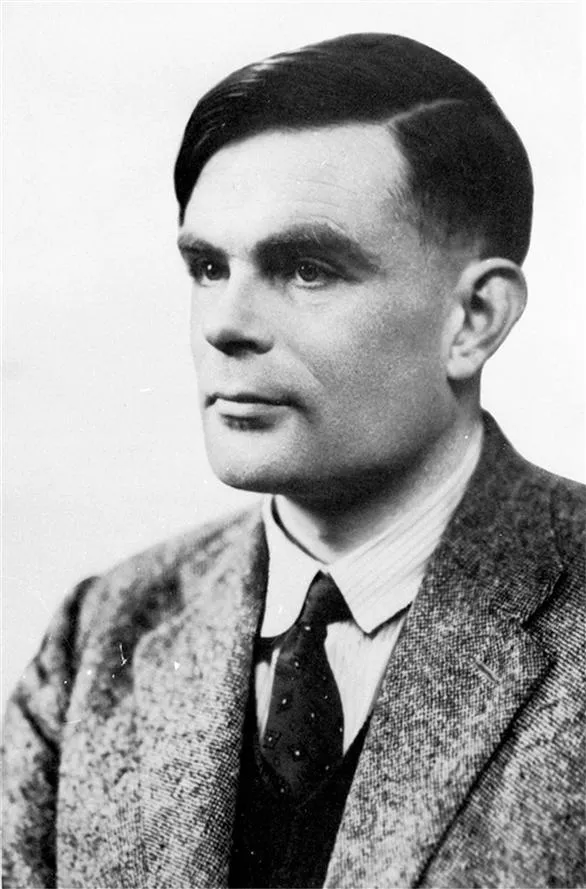

In this 2013 winner of the prestigious R.R. Hawkins Award from the Association of American Publishers, as well as the 2013 PROSE Awards for Mathematics and Best in Physical Sciences & Mathematics, also from the AAP, readers will find many of the most significant contributions from the four-volume set of the Collected Works of A. M. Turing. These contributions, together with commentaries from current experts in a wide spectrum of fields and backgrounds, provide insight on the significance and contemporary impact of Alan Turing's work.Offering a more modern perspective than anything currently available, Alan Turing: His Work and Impact gives wide coverage of the many ways in which Turing's scientific endeavors have impacted current research and understanding of the world. His pivotal writings on subjects including computing, artificial intelligence, cryptography, morphogenesis, and more display continued relevance and insight into today's scientific and technological landscape. This collection provides a great service to researchers, but is also an approachable entry point for readers with limited training in the science, but an urge to learn more about the details of Turing's work.- 2013 winner of the prestigious R.R. Hawkins Award from the Association of American Publishers, as well as the 2013 PROSE Awards for Mathematics and Best in Physical Sciences & Mathematics, also from the AAP- Named a 2013 Notable Computer Book in Computing Milieux by Computing Reviews- Affordable, key collection of the most significant papers by A.M. Turing- Commentary explaining the significance of each seminal paper by preeminent leaders in the field- Additional resources available online

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

How Do We Compute? What Can We Prove?

Hiding and Unhiding Information: Cryptology, Complexity and Number Theory

Building a Brain: Intelligent Machines, Practice and Theory

The mathematics of emergence: the mysteries of morphogenesis

Alan Mathison Turing by Max Newman

Andrew Hodges Contributes: A Comment on Newman’s Biographical Memoir

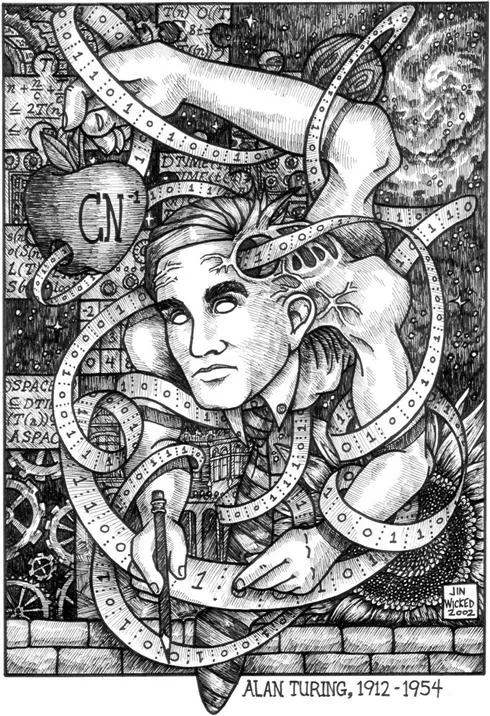

Alan Mathison Turing: 1912–1954a

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I. How Do We Compute? What Can We Prove?

- Part II. Hiding and Unhiding Information: Cryptology, Complexity and Number Theory

- Part III. Building a Brain: Intelligent Machines, Practice and Theory

- Part IV. The mathematics of emergence: the mysteries of morphogenesis

- Alan Mathison Turing by Max Newman

- On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem – A Correction

- On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem by A. M. Turing – Review by: Alonzo Church

- Computability and λ-Definability

- The -Function in λ-K Conversion

- Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals

- Practical Forms of Type Theory

- The use of Dots as Brackets in Church’s System

- The Reform of Mathematical Notation and Phraseology

- On the Gaussian error function

- Some Calculations of the Riemann Zeta function: On a Theorem of Littlewood

- Solvable and Unsolvable Problems

- The Word Problem in Semi-Groups with Cancellation

- On Permutation Groups

- Rounding-off Errors in Matrix Processes

- A Note on Normal Numbers

- Turing’s Treatise on the Enigma (Prof’s Book)

- Speech System ‘Delilah’ – Report on Progress

- Checking a Large Routine

- Excerpt from: Programmer’s Handbook for the Manchester Electronic Computer Mark II: Local Programming Methods and Conventions

- Turing’s Lecture to the London Mathematical Society on 20 February 1947

- Intelligent Machinery

- Computing Machinery and Intelligence

- Digital Computers Applied to Games

- Can Digital Computers Think?: Intelligent Machinery: A Heretical Theory: Can Automatic Calculating Machines Be Said To Think?

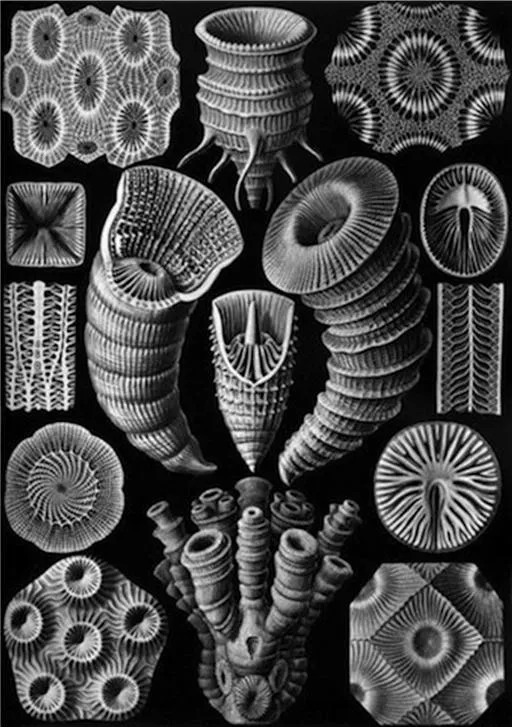

- The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis

- The Morphogen Theory of Phyllotaxis: I. Geometrical and Descriptive Phyllotaxis: II. Chemical Theory of Morphogenesis: III. (Bernard Richards) A Solution of the Morphogenical Equations for the Case of Spherical Symmetry

- Outline of the Development of the Daisy

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app