This is a test

- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles and Practice of Clinical Trial Medicine

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Clinical trials are an important part of medicine and healthcare today, deciding which treatments we use to treat patients. Anyone involved in healthcare today must know the basics of running and interpreting clinical trial data. Written in an easy-to-understand style by authors who have considerable expertise and experience in both academia and industry, Principles and Practice of Clinical Trial Medicine covers all of the basics of clinical trials, from legal and ethical issues to statistics, to patient recruitment and reporting results.

- Jargon-free writing style enables those with less experience to run their own clinical trials and interpret data

- Book contains an ideal mix of theory and practice so researchers will understand both the rationale and logistics to clinical trial medicine

- Expert authorship whose experience includes running clinical trials in an academic as well as industry settings

- Numerous illustrations reinforce and elucidate key concepts and add to the book's overall pedagogy

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Principles and Practice of Clinical Trial Medicine by Richard Chin,Bruce Y Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Pharmakologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedizinSubtopic

PharmakologieSection III

Key Components of Clinical Trials and Programs

Chapter 7 Endpoints

7.1 CHOOSING THE RIGHT ENDPOINTS

7.1.1 Characteristics of a Good Endpoint

As discussed in Chapter 4, an endpoint is defined as an overall outcome that a clinical trial aims to measure. This outcome can be a disease characteristic, health state, symptom, sign, or test (e.g., laboratory, radiological) results. Using the same analogies from Chapter 4, endpoints are like final scores in sports, final grades in college courses, and final box office receipts for a movie. Whether an intervention (e.g., drug, device or procedure) achieves an endpoint determines if it is a success or a failure. Regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) base drug and device approval decisions on clinical trial endpoints. Early in the development and evaluation of an intervention, endpoints are used to determine the safety and biological activity of an intervention. Later on, endpoints help decide whether a drug provides a clinical benefit. These results are then extrapolated to entire populations of patients based on similarities to the patients in the clinical trials.

The terms “endpoint” and “measure” are terms that are sometimes used loosely in clinical trials. For example, “endpoint” and “measure” are sometimes used to refer to any one of the following:

1. General clinical phenomenon being measured: the general disease or disease characteristic

• Blood pressure

• Congestive heart failure

2. Specific clinical phenomenon being measured: an aspect, usually the most significant aspect of a disease

• Systolic blood pressure

• Mean blood pressure

• Exacerbations of congestive heart failure

3. Specific clinical parameter at a specified interval: the aspect of the disease, with a specification regarding duration of observation or follow-up

• Systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks

• Congestive heart failure exacerbations over 6 months

4. Specific measure at a specified interval: same as #3, but with specification of the scale used for the measurement

• Systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks measured in mmHg

• Number of congestive heart failure exacerbations over 6 months

5. Specific measure at a specified interval, with measurement methods: same as #4, but with detailed method of obtaining the measurement

• Systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks measured in mmHg, measured after sitting for 5 minutes, repeated 3 times and averaged

• Number of congestive heart failure exacerbations over 6 months, as defined as need for hospitalization or ER visit

6. Specific measure at a specified interval, with analytic methods: same as #5, but with specification about how the data will be manipulated to draw inferences and conclusions

• Mean change in systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks compared to baseline measured in mmHg

• Percentage of patients who had at least 5 mmHg decrease in systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks compared to baseline

• Frequency of congestive heart failure exacerbations over 6 months, as defined as need for hospitalization or ER visit

7. Specific measure at a specified interval, with analytic methods and comparator group: similar to #6 but specifies a comparator group

• Mean change in systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks compared to baseline measured in mmHg, compared to placebo

• Frequency of congestive heart failure exacerbations over 6 months, as defined as need for hospitalization or ER visit, compared to frequency during the previous 6 months

Often, the details of the measure and endpoint are not well described, because sometimes the clinical phenomenon can be measured or characterized in different ways with similar results (for example, many drugs have collinear effects on mean blood pressure and systolic blood pressure so measurement of either yields similar results) or because the researcher chooses to use endpoints that have been used previously by previous researchers. In many cases, this is acceptable.

However, in many other situations, even slight changes in the measurement, the time interval, comparator group, etc. can have a profound effect on the ability of a study to answer the question, the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn, the sample size, and so on. It is therefore imperative that the endpoint and measure be chosen with clear understanding of the implications of the choice.

It is important to distinguish between measure and endpoint. We define “measure” as a numeric, mathematical, or other way of assessing a clinical event or characteristic. A measure maps some aspect of the item or phenomenon onto a scale. Some common measures include mmHg, mortality rate, and number of days in the intensive care unit.

We define “endpoint” as the clinically relevant property that is being measured. For example, “mmHg” is a measure, and “change in mean blood pressure after 6 weeks of therapy” is an endpoint. The measure is used to quantify the endpoint. An endpoint is expressed as a measure that is put in context, with specified time interval and analytical methods.

The endpoints chosen can dramatically affect results and interpretation of a clinical trial. In sports and college courses, the scoring system and grading criteria can dramatically affect the final scores (and hence the winners and losers) and final grades (and hence the honor students and those who flunk), respectively. For example, using a racket to hit a ball past your opponent will result in points in tennis, but not in basketball. Similarly, writing a nice essay may help your grade in a history class, but not in a mathematics class. Similarly, if inappropriate endpoints are used, then a clinical trial may mistakenly show that the intervention has or does not have a benefit or that the intervention is safe or not safe.

As discussed in Chapter 4, there are many different ways to measure the same phenomenon. We mentioned that even a simple question like “how far is it from San Francisco to Chicago?” can have a myriad of different answers. Therefore, it is crucial to specify the criteria being used. Measuring the air, driving, or postal distance from downtown to downtown, SFO to O’Hare, or city limit to city limit can give very different answers. Therefore, in clinical trials, it is essential to be very specific when choosing and defining endpoints.

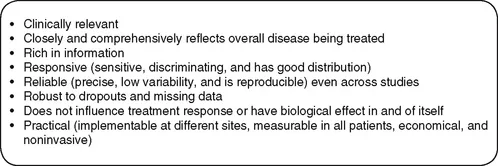

Figure 7.1 lists the characteristics of a good endpoint. We will discuss clinical relevance and responsiveness in detail in the following sections but there are several other key characteristics of a good clinical endpoint.

FIGURE 7.1 Characteristics of a good endpoint.

First, the endpoint must closely and comprehensively reflect the overall disease being treated. Using our previous analogies, counting only the number of field goals made would not be an appropriate way to score a football game, and considering only class participation may not be the best way to grade a freshman history class. Field goals only represent one part of a football game, and class participation may reflect only one aspect of a student’s abilities and knowledge. Similarly, an endpoint that only captures one aspect or component of a disease may not suffice. For example, if the disease being treated were systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an endpoint focusing just on skin manifestations may miss the cardiac, pulmonary, and renal manifestations of lupus. If the intent of the therapy were to improve the overall status of a patient with SLE, a skin manifestations measure would be an inappropriate endpoint. On the other hand, if the drug is only intended to improve skin manifestations, this endpoint may be acceptable.

Second, the endpoint should capture enough appropriate information for you to analyze and draw appropriate conclusions. In general, knowing more useful information is bette...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- Section I: Overview

- Section II: The General Structure of Clinical Trials and Programs

- Section III: Key Components of Clinical Trials and Programs

- Section IV: Conduct of the Study

- Section V: Analysis of Results

- Appendices

- Index