- 978 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Wine Science, Fourth Edition, covers the three pillars of wine science: grape culture, wine production, and sensory evaluation. It discusses grape anatomy, physiology and evolution, wine geography, wine and health, and the scientific basis of food and wine combinations. It also covers topics not found in other enology or viticulture texts, including details on cork and oak, specialized wine making procedures, and historical origins of procedures.

New to this edition are expanded coverage on micro-oxidation and the cool prefermentative maceration of red grapes; the nature of the weak fixation of aromatic compounds in wine – and the significance of their release upon bottle opening; new insights into flavor modification post bottle; the shelf-life of wine as part of wine aging; and winery wastewater management. Updated topics include precision viticulture, including GPS potentialities, organic matter in soil, grapevine pests and disease, and the history of wine production technology.

This book is a valuable resource for grape growers, fermentation technologists; students of enology and viticulture, enologists, and viticulturalists.

New to this edition:

- Expanded coverage of micro-oxidation and the cool prefermentative maceration of red grapes

- The nature of the weak fixation of aromatic compounds in wine – and the significance of their release upon bottle opening

- New insights into flavor modification post bottle

- Shelf-life of wine as part of wine aging

- Winery wastewater management

Updated topics including:

- Precision viticulture, including GPS potentialities

- Organic matter in soil

- Grapevine pests and disease

- History of wine production technology

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

The chapter acquaints the reader with two critical aspects of wine science: grape culture and wine production. It begins with a brief history of wine production and grape cultivation in the Near East, and its subsequent spread to and development in Mediterranean and Central Europe. The unique properties of grapes and wine yeasts, relative to wine production, are highlighted, followed by an account of the commercial importance of grapes and wine in modern commerce. The next section outlines wine classification and a review of what is meant by wine quality. The chapter finishes with a brief account of the health-related aspects of moderate wine consumption and its positive social image.

Keywords

Wine; grape culture; wine history; wine yeasts; wine classification; wine and health

Grapevine and Wine Origin

Wine has an archeological record potentially dating back to 5500 B.C. Residues, likely to be from wine (or grape juice), were found in a jar in Hijji Firuz Tepe, in the northern Zagros Mountains of Iran, close to modern-day Turkey (McGovern et al., 1996). The site dates back to the early to mid-fifth millennium B.C. Identification of the residues was based on the presence of calcium tartrate crystals. Tartaric acid, one of the two major grape acids, is rarely found in other fleshy fruit. In addition, no other fruit indigenous to the region produces significant amounts of tartaric acid.

Hijji Firuz Tepe is situated on the southeastern rim of an indigenous grapevine habitat. Therefore, grapes could have been growing close by. The narrow-necked, ceramic vessel also contained traces of resin (terebinth, from Pistacia terebinthus). Resin has often been found in ancient wine amphoras (two-handled, elongated, clay, wine/storage vessels). This increases the likelihood that the tartrate crystals came from wine as opposed to grape juice. Resin was extensively used as a preservative and flavorant, as well as to waterproof porous clay vessels.

Pyriform vessels, appearing to contain wine residues, have also been found south of Hijji Firuz Tepe, at Goden Tepe, dating from 3100–2900 B.C. From the distribution of the residues in the vessels, they appeared to have been laid on their side for storage (Badler, 1995). The vessels also possessed an inner slip of fine, fired clay. This made them comparatively nonporous. They were also apparently sealed with clay closures (Michel et al., 1993).

However, if all that is needed for the discovery of wine production is an established agriculture, in a region where grapes grow indigenously, then current estimates for wine’s first discovery may be short by some 4000 years. For example, the complex buildings discovered in southeastern Turkey (Göbekli Tepe), dating from about 9000 B.C. (Schmidt, 2010), clearly needed an established agriculture to support a large labor force. It is located in a region where vines could have been endemic.

Evidence of domesticated grapevines (Ramishvili, 1988), and residues in pottery from Georgia, suggests that wine production was well dispersed throughout the Caucasus in the Neolithic period (McGovern personal comm.). A cave in neighboring Armenia has been tentatively identified as a site where grapes may have been crushed and the juice collected, possibly for wine production (Barnard et al., 2011). The site dates back to about 4000 B.C. Vessels at the site also show evidence consistent with the presence of malvidin (the most common grape anthocyanin pigment). Malvidin occurs in few other fruit indigenous to the region.

Older examples of fermented beverages have been discovered (McGovern et al., 2004), but they appear to have been produced from a mixture of rice, honey, and fruit (hawthorn and/or grape). Such beverages were being produced in China as early as 7000 B.C.

As noted, the presence of wine residues is usually suggestive of the presence of insoluble calcium salts of tartaric acid. Additional procedures, designed to identify grape tannin residues, are in development (Garnier et al., 2003). Other than the technical problems associated with identifying wine residues (e.g., differentiation between dried grape juice vs. wine residues), there is the thorny issue of what actually constitutes wine. Does spontaneously fermented grape juice qualify as wine, or should the term be restricted to juice fermented and stored in a manner capable of retaining its wine-like properties? The latter would suggest purposeful intent, rather than a simple fortuitous event.

Because of low yield, seasonal availability, and localized production (on trees or straddling screes), opportunities for collecting significant quantities of wild grapes would have been limited. Wine production, as normally defined, also demands some form of impervious, ideally sealable, container. Thus, any significant wine production probably postdates the development of agriculture and a settled lifestyle. Even accidental seed germination in rubbish piles would take several seasons before the vines would produce fruit. Admittedly, this is all speculative. Thus, the timing and events that ultimately lead to the production of wine, and the spread of this technology, may always be an enigma. Nonetheless, production of narrow-necked pottery was in existence at least 8000 years ago, and the availability of wood-derived resins (sealing the vessels) made wine storage possible. The use of wineskins is another option, but one for which no archaeological evidence remains, or is likely ever to be found. The presence of third and fourth century B.C. carbonated grape seed remains from the Jordan Valley suggests that viticulture, and possibly winemaking, had already spread outside the indigenous range of wild grapevines. This suggests purposeful cultivation (McGovern et al., 1997; Zohary and Hopf, 2000).

However, the first unequivocal evidence of intentional winemaking appears in representations of wine presses from the reign of Udimu (Egypt), some 5000 years ago (Petrie, 1923). Wine residues have also been found in amphoras, specifically so marked, in many ancient Egyptian tombs. The earliest dates from the reign of King Semerkhet in the 1st Dynasty (2920–2770 B.C.) (Guasch-Jané et al., 2004). Amphoras noted to contain white and red wine were discovered in the tomb of King Tutankhamun (1325 B.C.) (Lesko, 1977). The existence of red wine residues was confirmed by the presence of syringic acid, an alkaline breakdown product of malvidin-3-glycoside. The same technique has been used to establish the red grape origin of the ancient Egyptian drink – Shedeh (Guasch-Jané et al., 2006). Additional details about Egyptian wine jars, and their sealing, can be found in McGovern et al. (1997) and Lesko (1977). Egyptian amphoras often possess indications of the wine’s origin, vintage, vineyard, and occasionally the name of the winemaker. Similar markings have been found on Roman amphoras in Pompeii, occasionally including marks indicating the person to whom the wine was being sent (Jashemski, 1975). Although analysis of DNA remains found in amphoras has begun (Cavalieri et al., 2003; Hansson and Foley 2008), they have not as yet been used to investigate the degree of relatedness to current cultivars. This is probably only a matter of time.

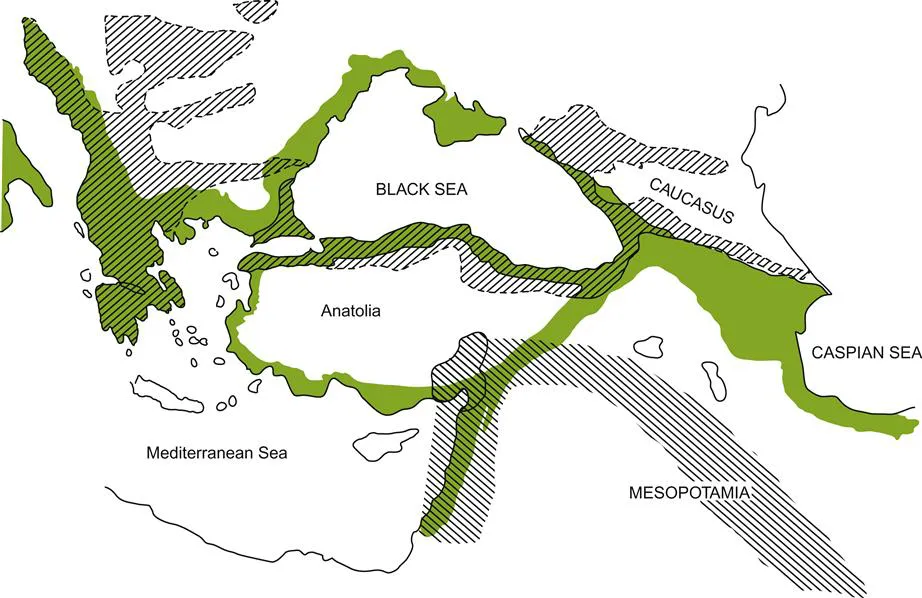

Most researchers believe that winemaking was discovered, or at least evolved, in the southern Caucasus. This area includes parts of present-day north- and southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. It is also generally thought that domestication of Vitis vinifera occurred within this region. Remains of what have been interpreted as domesticated grape remains have been found in a Neolithic village in the Transcaucasian region of Georgia (Ramishvili, 1983).

Although grapes possess an extensive epiphytic flora, most of the yeast species are unable to completely ferment the sugar content of the juice. Only Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast), and closely related species (forms), are sufficiently alcohol resistant to complete the task, essential for producing a potentially stable wine. Surprisingly, S. cerevisiae is not a major or typical member of the skin flora. The natural habitat of the ancestral forms of S. cerevisiae (S. paradoxus) appears to be the bark and sap exudate of oak trees (Phaff, 1986). If so, the habit of grapevines growing up trees such as oak, and the ancient, joint harvesting of grapes and acorns for food (Bohrer, 1972; Mason, 1995) may have encouraged the inoculation of grape juice with S. cerevisiae.

The proximity or overlap in the distributions of oak (Meusel, 1965), wild grapes (Levadoux, 1956), the origins of Western agriculture (Bohrer, 1972; Zohary and Hopf, 2000), and advances in pottery production may have fostered the development of winemaking in the southern Caucasus, and especially southeastern Anatolia (Fig. 1.1). In addition, it may not be pure coincidence that most major yeast-fermented beverages and foods (wine, beer, cider, mead, and bread) have their presumptive origins in the same region.

Ancient literary evidence has been interpreted by Civil (1964) to suggest that grapes acted as the initial source of yeasts that incited beer production. The earliest evidence for beer production also occurs later than wine, as its modern expression required both the domestication and cultivation of barley, and the dis-covery of malting (the partial germination of the grain). Enzymes liberated during barley germination hydrolyze starch to the sugars needed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nonetheless, even without malting, if the barley were first roasted, or a ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Author

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Grape Species and Varieties

- 3. Grapevine Structure and Function

- 4. Vineyard Practice

- 5. Site Selection and Climate

- 6. Chemical Constituents of Grapes and Wine

- 7. Fermentation

- 8. Post-Fermentation Treatments and Related Topics

- 9. Specific and Distinctive Wine Styles

- 10. Wine Laws, Authentication and Geography

- 11. Sensory Perception and Wine Assessment

- 12. Wine, Food and Health

- Glossary

- Color Plate

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wine Science by Ronald S. Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.