- 640 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Vein Book

About this book

The Vein Book is a comprehensive reference on veins and venous circulation. In one volume it provides complete, authoritative, and up-to-date information about venous function and dysfunction, bridging the gap between clinical medicine and basic science. It is the single authoritative resource which consolidates present knowledge and stimulates further developments in this rapidly changing field.

- Startling new treatment for venous thromboembolic disease

- Details the condition of varicose veins, spider veins and thread veins and discusses treatment options

- Radically effective treatment of leg ulcer

- Clarification of the pathophysiology of Venous Insufficiency

- Molecular mechanisms in the cause of varicose veins

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

MedicineCHAPTER 1

Historical Introduction

ALBERTO CAGGIATI and CLAUDIO ALLEGRA

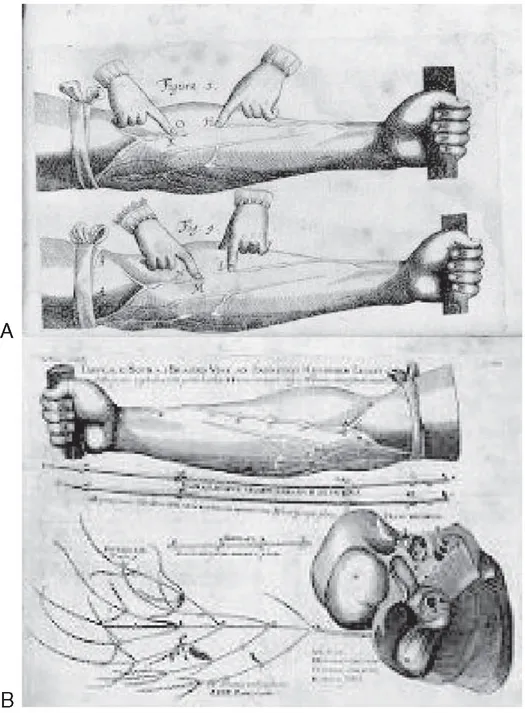

The first systematic description of the venous system was given by André Vesale (alias Vesalius) in De humanis corporis fabrica. He differentiated the internal coat of the veins in two layers. The internal one contained contractile fibers, though “dissimilar from those of skeletal muscles, arranged, from within outwards, circularly, obliquely and longitudinally.” Giovanni Battista Canano from Ferrara was the first to describe venous valves (ostiola sive opercula) in the renal, azygos, and external iliac veins. Further, sporadical descriptions of venous valves were given by the Spanish anatomist Ludovicus Vassaeus, and, one year later, by Charles Estienne (apophyses membranarum). The mechanisms allowing blood to flow centripetally along the veins were described more than two hundred years ago. The vis a tergo was described by Richard Lower: “the return of the venous blood is the result of the impulse given to the arterial blood.” Furthermore, Lower acknowledged an important role of the venarum tono in venous return and described the effects of muscular pumping. Hippocrates was the first to deal with the pathogenesis and epidemiology of varicose disease when he affirmed that varicose veins were more frequent in Scythians due to prolonged time spent on the horseback with the legs hanging down. Clinical semiotics started in 1806 when the Swiss surgeon, Tommaso Rima, described a simple test for the diagnosis of saphenous reflux. And in 1846, Sir Benjamin Brodie described a method of testing for incompetent valves by constriction of the limb and palpation.

Since the fifth century BC, the heart has been regarded as the center of the vascular system (Empedocles of Agrigentum; 500–430 BC). In the great Epic of India, “Mahabharata,” it was stated that “all veins proceed from the heart, upwards, downwards and sideways and convey the essences of food to all parts of the body.” The Chinese Wang Shu So reported in his Mei ching, that “the heart regulates all the blood in the body … The blood current flows continuously in a circle and never stops …” Herasistratus (310–250 BC) was so close to the discovery of the circulation to guess the existence of capillaries: “… the blood passes from the veins into arteries thorough ‘anastomoses,’ small inter-communicating vessels …”

These correct theories were darkened by Hippocratic dogma for centuries. Hippocrates of Cos, the “father of the Medicine” (460–377 BC) affirmed in “De Nutritione” that the liver is the “root” of all veins and that the veins alone contain blood destined for the body’s nourishment. Arteries would contain an elastic ethereal fluid, the “spirit of life.” This wrong convincement, based upon the Pythagorean doctrine of the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile), remained the basis for medical practice for more than 2000 years!

As irrational as this theory seems to us today, more than three centuries (1316–1661) passed until it was abolished. Many authors confuted Hippocratic theories, allowing, and sometimes anticipating, Harvey’s discovery. In 1316, Mondino de Luzzi furnished a rudimental but exact description of the circulatory system that was omitted by all subsequent authors: “… Postea vero versus pulmonem est aliud orificium venae arterialis, quae portat sanguinem ad pulmonem a corde; quia cum pulmo deserviat cordi secundum modum dictum, ut ei recompenset, cor ei transmittit sanguinem per hanc venam, quae vocatur vena arterialis; est vena, quia portat sanguinem, et arterialis, quia habet duas tunicas; et habet duas tunicas, primo quia vadit ad membrum quod existit in continuo motu, et secundo quia portat sanguinem valde subtilem et cholericum …” The same occurred to the Spanish Ludovicus Vassaeus and Miguel Servetus. The anatomy of the cardiovascular system was so well depicted by Vassaeus (De Anatomen Corporis Humani tabulae quator, 1544) that Marie Jean Pierre Florens affirmed that he “… described the blood circulation a century before William Harvey …” In 1546, the anti-Arabist theologician and physician Servetus exactly described the pulmonary circulation: “… the blood enters the lungs by the way of the pulmonary artery in greater quantities than necessary for their nutrition, mixes with the pneuma and returns by way the pulmonary veins …” Servetus’ discovery did not diffuse between contemporary physicians, probably because it was reported in a theological book. Servetus’ theories were so innovative that he was accused of heresy by Calvinists and burned. Andrea Cesalpino, Professor of Medicine at Rome, first identified the function of the valves (… certain membranes placed at the openings of the vessels prevent the blood from returning …) and the centripetal direction of the flow in the veins (1571). He also supposed the existence of “vasa in capillamenta resoluta” (capillaries) and affirmed that in the lung, the blood “… is distributed into fine branches and comes in contact with the air …” (1583). Finally, he coined the term “circulation.” According to important historians like Florens, Richet, and Castiglioni, Cesalpino’s groundwork determined the Harvey’s revolution.

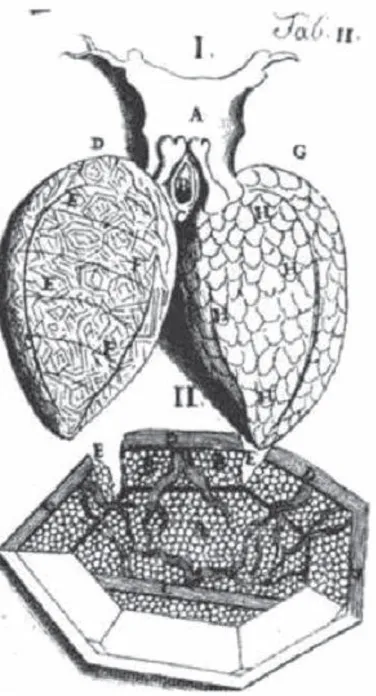

In 1628, William Harvey explained in his De Motu Cordis the theory of the blood circulation (see Figure 1.1). However, the discovery of the circulation cannot be considered complete until 1661, when Marcello Malpighi demonstrated by microscopy the existence of the capillaries in his De Pulmonibus (see Figure 1.2).

VENOUS ANATOMY

The first systematic description of the venous system was gi...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Contributing Authors

- Preface

- Prologue

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Historical Introduction

- Chapter 2: Venous Embryology and Anatomy

- Chapter 3: Epidemiology of Chronic Peripheral Venous Disease

- Chapter 4: Venous Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathophysiology

- Chapter 5: Role of Physiologic Testing in Venous Disorders

- Chapter 6: Inappropriate Leukocyte Activation in Venous Disease

- Chapter 7: Molecular Basis of Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 8: Chronic Venous Insufficiency: Molecular Abnormalities and Ulcer Formation

- Chapter 9: Pathophysiology of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 10: Mechanism and Effects of Compression Therapy

- Chapter 11: Classifying Venous Disease

- Chapter 12: Risk Factors, Manifestations, and Clinical Examination of the Patient with Primary Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 13: Sclerosing Solutions

- Chapter 14: Sclerotherapy Treatment of Telangiectasias

- Chapter 15: Complications and Adverse Sequelae of Sclerotherapy

- Chapter 16: Laser Treatment of Telangiectasias and Reticular Veins

- Chapter 17: Overview: Treatment of Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 18: Ultrasound Examination of the Patient with Primary Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 19: Conventional Sclerotherapy versus Surgery for Varicose Veins

- Chapter 20: Sclerotherapy and Ultrasound-Guided Sclerotherapy

- Chapter 21: Sclerofoam for Treatment of Varicose Veins

- Chapter 22: Sclerosants in Microfoam: A New Approach in Angiology

- Chapter 23: Ultrasound-Guided Catheter and Foam Therapy for Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 24: Principles of Treatment of Varicose Veins by Sclerotherapy and Surgery

- Chapter 25: Inversion Stripping of the Saphenous Vein

- Chapter 26: Neovascularization: An Adverse Response to Proper Groin Dissection

- Chapter 27: Principles of Ambulatory Phlebectomy

- Chapter 28: Powered Phlebectomy in Surgery of Varicose Veins

- Chapter 29: Endovenous Laser (EVL) for Saphenous Vein Ablation

- Chapter 30: Effects of Different Laser Wavelengths on Treatment of Varices

- Chapter 31: VNUS Closure of the Saphenous Vein

- Chapter 32: Treatment of Small Saphenous Vein Reflux

- Chapter 33: Classification and Treatment of Recurrent Varicose Veins

- Chapter 34: Use of System-Specific Questionnaires and Determination of Quality of Life after Treatment of Varicose Veins

- Chapter 35: Pelvic Congestion Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment

- Chapter 36: The Epidemiology of Venous Thromboembolism in the Community: Implications for Prevention and Management

- Chapter 37: Fundamental Mechanisms in Venous Thrombosis

- Chapter 38: Congenital and Acquired Hypercoagulable Syndromes

- Chapter 39: New Ways to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism: The Factor Xa Inhibitor Fondaparinux and the Thrombin Inhibitor Ximelagatran

- Chapter 40: Diagnosis of Deep Vein Thrombosis

- Chapter 41: Thrombotic Risk Assessment: A Hybrid Approach

- Chapter 42: Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in the General Surgical Patient

- Chapter 43: Conventional Treatment of Deep Venous Thrombosis

- Chapter 44: The Diagnosis and Management of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia

- Chapter 45: Operative Venous Thrombectomy

- Chapter 46: Permanent Vena Cava Filters: Indications, Filter Types, and Results

- Chapter 47: Complications of Vena Cava Filters

- Chapter 48: Temporary Filters and Prophylactic Indications

- Chapter 49: Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Venous Thrombosis

- Chapter 50: Percutaneous Mechanical Thrombectomy in the Treatment of Acute Deep Venous Thrombosis

- Chapter 51: Mechanical Thrombectomy and Thrombolysis for Acute Deep Venous Thrombosis

- Chapter 52: Diagnosis and Management of Primary Axillo-Subclavian Venous Thrombosis

- Chapter 53: Subclavian Vein Obstruction: Techniques for Repair and Bypass

- Chapter 54: The Primary Cause of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 55: Conventional Surgery for Chronic Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 56: Subfascial Endoscopic Perforator Vein Surgery (SEPS) for Chronic Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 57: Ultrasound-Guided Sclerotherapy (USGS) of Perforating Veins in Chronic Venous Insufficiency

- Chapter 58: Perforating Veins

- Chapter 59: Importance, Etiology, and Diagnosis of Chronic Proximal Venous Outflow Obstruction

- Chapter 60: Treatment of Iliac Venous Obstruction in Chronic Venous Disease

- Chapter 61: Endovenous Management of Iliocaval Occlusion

- Chapter 62: Popliteal Vein Entrapment

- Chapter 63: Valvuloplasty in Primary Venous Insufficiency: Development, Performance, and Long-Term Results

- Chapter 64: Prosthetic Venous Valves

- Chapter 65: Post-Thrombotic Syndrome: Clinical Features, Pathology, and Treatment

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Vein Book by John J. Bergan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.