![]() RETROSPECT

RETROSPECT![]()

REINTRODUCTION

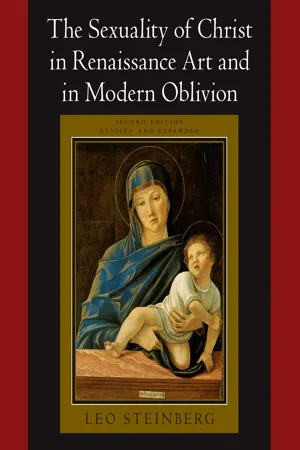

Gladly would the present publisher have issued this book in a second edition without doubling its size, but I said no; I would not deprive it of the interest accrued since 1983. The book had elicited questions that could not be dodged without gross discourtesy, especially those posed in goodwill or in good-natured banter, and more especially those intended to kill. These last were the more intriguing to deal with, but I have tried to resist playing favorites.

For easy reference, given the exorbitant length of its eleven-word title, the book will be cited henceforth as SC (Sexuality of Christ . . .). For the convenience of browsers, the contraction will be decoded again near the start of each chapter. The temptation to call this second edition Double or Nothing has been suppressed. SC it is.

It is followed now by a somewhat discursive Retrospect spread through ten chapters. Chapter 1, challenged to answer new questions, reflects on the Early Christian conception of a phased human nature—initially paradised, then corrupted, at last redeemed. At each of these stages, sexuality, as theologians conceived it, turns out to be crucial. Chapter 2 introduces new visual evidence, some of it come to light in consequence of the original publication. These images dwell on what is now widely recognized as Christianity’s greatest taboo, Christ’s sexuality.1 It hardly needs saying that what becomes a taboo must in some way exist.

How this existence may be denied or explained away by embarrassed modern interpreters is the subject of chapter 3. Chapter 4, a theological interlude, considers the Incarnate as the New Adam, and his sexuality as necessarily antecedent to sin, i.e., prelapsarian. Chapter 5 discusses images that violate the ancient taboo at its quick: the subject is the motif of the phallic erection in its positive thereness, its “ibiquity”—a word I had to make up to avoid pointing.

Chapters 6–9 are polemical. The two scholars who worked hardest to deflate SC’s argument receive careful attention. But more casual objectors, solicitous about the oblivion mentioned in SC’s title, are not neglected; partly because they articulate common prejudice, and with this further aim: to puncture the presumption of book reviewers that their verdict is destiny. To review judgmental decisions, to make judges accountable for their opinions, seems only just. It is also good sport.

In the course of this exercise, the topics keep moving and the focus becomes kaleidoscopic. As the assaults come on many fronts, deploying dissimilar weapons, so the defense. Hence the many shifts of terrain and the inclusion of major and minor digressions, from the depictability of the Trinity and the claims for a “masculofeminine,” or female, Christ to the aesthetics of the U.S. Post Office.

One theme runs fugally through this Retrospect: the supposed need for extraneous texts as indispensable to interpretation. I suspect, and hope to demonstrate, that such texts obscure, quite as often as they illuminate, Renaissance pictures. These, carefully watched, appear surprisingly capable of self-explanation, or of explaining each other. To honor this capability, the polemical chapters strive continually against the claims of what I call “textism”—a coinage just vile enough to be aptly repugnant. Of course, I refer the term only to textism’s prohibitive scowl, not to the truism that some images may be clarified by some texts. Textism as I define it is an interdictory stance, hostile to any interpretation that seems to come out of nowhere because it comes out of pictures, as if pictures alone did not constitute a respectable provenance. Like dreams in Mercutio’s famous don’t-worry speech (Romeo and Juliet, I, iv), picture-based interpretations are thought to be spun of thin air, begot of vain fantasy. To the textist, a close attention to whatever images may serve up seems erratic, a Rapid Eye Movement that yields no reliable reading unless certified by something in writing. As if the literary sources available to the exegete were unambiguous or necessarily isomorphic with the content of pictures. (Chapter 7 cross-examines three adversarial texts summoned by as many contenders against the book.) To my mind, the deference to far-fetched texts in mistrust of pictures is one of art history’s inhibiting follies. It surely contributed to the obnubilation, the Cloud of Unseeing, that caused Christ’s sexual nature as depicted in Renaissance art to be overlooked.

A few words about SC’s initial reception. It was mixed. While art historians took opposing positions, critics from the side of religion, regardless of denomination, seemed to find the book orthodox and to the point. To put it another way: the religious admitted the images reproduced in SC as valid, primary evidence; the right to dismiss such evidence was claimed only by art historical colleagues.

Neither gender nor age prejudiced the response to the book, but a notable reactivity differential showed up along ethno-cultural lines. Whereas American and Continental critics without exception kept a straight face in discussing SC, the British, with rare exceptions, came on punning and winking. Innuendo abounded: “‘Stimulating’ is not perhaps the most appropriate word to use in speaking of a book entitled ‘The Sexuality of . . .’” Or, “Steinberg’s book has aroused, if that’s the right word. . . .” One reviewer (adopting a title of Samuel Beckett’s) warned of “More Pricks than Kicks.” Another referred to the censorship discussed in SC as “painting out penises and painting in loincloths . . . and generally making addenda to pudenda.” A famous author with tongue in cheek reported that “the naked Christ-child . . . who cheerfully waves His slightly tumescent willy about . . . turns out to stand for a solemn aspect of the Incarnation.” In sum: “[Steinberg’s] argument makes you bite back giggles. . . .”2

Not that the British reflex to SC was all giggly: a few sobersides managed unsmiling denunciation, and they succeeded in disappearing the book within weeks.3 The dispatch with which the firm of Faber and Faber unloaded its hot potato on the New York remainder market recalls the resourcefulness of the Sienese who, in 1357, having unearthed a statue of Venus and finding it to be evidently demonic, reburied the idol in Florentine territory to work its blight there on the enemy.

A somberer note was sounded by an eminent British philosopher, reviewing SC for The New York Times: “The most disturbing aspect of this strange, haunting book . . . is the resolute silence it maintains on all alternative views.”4 This rebuke has been taken to heart. Conscientiously, the following chapters attend (among other distractions) to every alternative view produced by the criticism of the past decade.

Unfortunately, the admission of opposing viewpoints has trapped me in a predicament I can see no way out of: it has maneuvered me into misrepresenting the book’s reception as wholly negative. But, then, to have presented a fairer balance by mentioning nods of approval would have injured my reputation for modesty; which I herewith confirm by relegating the more substantive raves to a footnote.5

Meanwhile, to placate the philosopher and to relieve my benign book of its “most disturbing aspect,” I have breasted the full range of objections. For instance: where the display of the genitals, the ostentatio genitalium observable in Renaissance Adorations, led critics to offer alternative explanations—most of them euphemizing the genital demonstration as “nudity”—I recognize the following six counter-proposals:

(1) The Infant’s nudity is no problem; in the warmth of Renaissance Italy (though perhaps not in wintry Flanders), babies were normally naked, so why not baby Jesus? (See p. 353.)

(2) The Child is stripped bare because Renaissance artists compulsively copied antique models of infant anatomy.

(3) The Child appears nude because the Holy Family was too poor to buy swaddling (p. 346).

(4) The Child is denuded to assure both shepherds and Magi that the Newborn is not a girl but the male Messiah foretold (p. 350).

(5) The Child’s loins are unveiled to evoke the redemptive blood first shed at the Circumcision. This was SC’s suggestion, but was not meant to exclude other considerations. The critics’ novel recourse is to declare every depicted exposure a forward reference to the Passion.

(6) Where the symbolism in Adoration scenes is Eucharistic, the Child as the implied Host of the altar cannot be other than nude. (None of SC’s critics said as much, but they should have.6)

Having weighed each of the foregoing alternatives, even the lightest, I find such discipline conducive to a rare sense of virtue; as if one were following the Church Father who wrote in the midst of some controversy: “I shall treat this question so carefully as to seem to be seeking the truth along with my questioners.”

Speaking of St. Augustine brings up another dilemma: whether to rest one’s case or risk the grating effect of polemics, insufferable even in a controversialist of saintly stature. Reading, for instance, the aged Augustine’s tract Against Julian, one’s respect for the mighty bishop wavers in proportion to his disputatiousness. Augustine flails and pounds at the underdog, kicking him when he’s down, so that all one’s boy scout morality wells up to protest. Poor Julian’s “fragile and oversubtle novelty is crushed,” crows the saint. “Behold, your whole case is overthrown, ruined, and like the dust which the wind sweeps from the face of the earth.” While the winner exults to have “answered and refuted all [contrary] arguments,” the loser (“a detestable heretic” with a “mind subverted by the vanity of [his] boasting”) grovels in “damnably and abominably impious error.” His “presumptuous attack” is but “obstinacy,” “headlong boldness” and “madness” “You are mistaken, wretchedly mistaken, if not also abominably mistaken”—and so on and on.7

Repelled by these cruel punches, one inclines to forget the stakes (the institution of the dogma of Original Sin); forget that it was Bishop Julian who had started the fight (with a four-book attack on Augustine’s “disgusting” and “blasphemous” treatise On Marriage and Concupiscence); forget how much of Augustine’s counter-invective was period style; forget that Julian’s preceding onslaught had been personally abusive, and that his epithets (“false, foolish, and sacrilegious”) may have struck wounds still smarting as Augustine strikes back. But as we read, Julian’s own scathing (unless framed in his enemy’s refutation) is not at hand; what comes down to us in Contra Julianum is his prostration, suffering kick after kick.8 Not the most agreeable reading. And now a no-win situation invites me to emulate Julian’s antagonist at his meanest, in the role of the bully.

Whether to hold one’s peace or talk back: the defensive parts of this Retrospect seemed to need writing because many took SC to have desecrated a precious taboo. SC did not so much break it as observe that the taboo had been breached in Renaissance art. Now insofar as no such breach is admitted, SC’s author will have invented, like St. Augustine’s defrocked Bishop Julian, “fragile and oversubtle novelties.” And one shudders to think what might be the motive for such impious inventions.

On the other hand: while defense may be admirable in litigation, karate, or chess, it rarely scores in response to one’s personal critics. One reads in old-fashioned biographies about men of mettle who take it on the chin, treating hostility—I believe the phrase is—“with the contempt it deserves.” But such ataraxy is easier envied than imitated; and it is this felt envy which defines the second of the three quandaries I leave unresolved.

The gravest of my insoluble problems concerns the reproductions, their number now raised to three hundred, all gray-and-white and some very small. They are—they ought to have been—the book’s beating heart. And how effectively they would have prevailed had the book been producible for large sales, with no expense spared to show off each image full page, printed on smoothest stock in highest-grade inks, glorious in color and clarity. But SC is not that kind of book. So, when the above-mentioned philosopher complained that “if anything in the orbit of [this] discussion does deserve the term ‘scandalous,’ it is the quality of the illustrations,” he was (I think inadvertently) sneering at poverty, which is not a nice thing to do.

One Londoner held it against the pictures that “their most vital part . . . is often well-nigh invisible.” True, alas, and all too apparent, but preferable to the sin of reproducing magnified close-ups of “vital parts.” Accordingly, while some of the reproductions detail one group or one figure, phallocentric framing was barred; not only on grounds of good manners, but because such practice would have thwarted the artists’ intent, which was not to isolate, but to integrate the sexual member in the body of Christ. Where that member showed up less than clear, the cantankerous felt free to impugn my eyesight, as if dubious evidence had been smuggled in because it was subfusc enough to permit unverifiable claims. This is a predicament which a modestly produced book has to live with.

But the book’s reproductions don’t close the issue. Counting on the efficacy of the art they are signals of, they initiate delayed-action effects. During the past dozen years, many have seen their skepticism about SC’s argument shrink away in the presence of the originals. The pictures take over, wanting no further pleading. Even in queasy England, I hear, the claims of the ostentatio genitalium are winning out. Not, of course, among scholars who are ey...