![]()

PART I

RIGHT AROUND 1910 . . .

Con un poco de método y laboriosidad se es erudito. Con otro poco de cuidado, se es castizo. Lo que no se puede ser ni con método, ni con laboriosidad, ni con cuidado, es pensador . . . ten talento y escribe lo que te plazca, cuando ya no tengas talento métete a erudito.

With a little method and industriousness one can be an erudite person. With a little more care, one becomes castizo [a purist in the use of language]. What one cannot be with either method or labor, not even with care, is a thinker . . . be talented and write whatever you want, when you run out of talent become an erudite scholar.

—Amado Nervo, “Algo sobre la erudición y el estilo,” Obras completas, vol. 23 (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 1949), 278

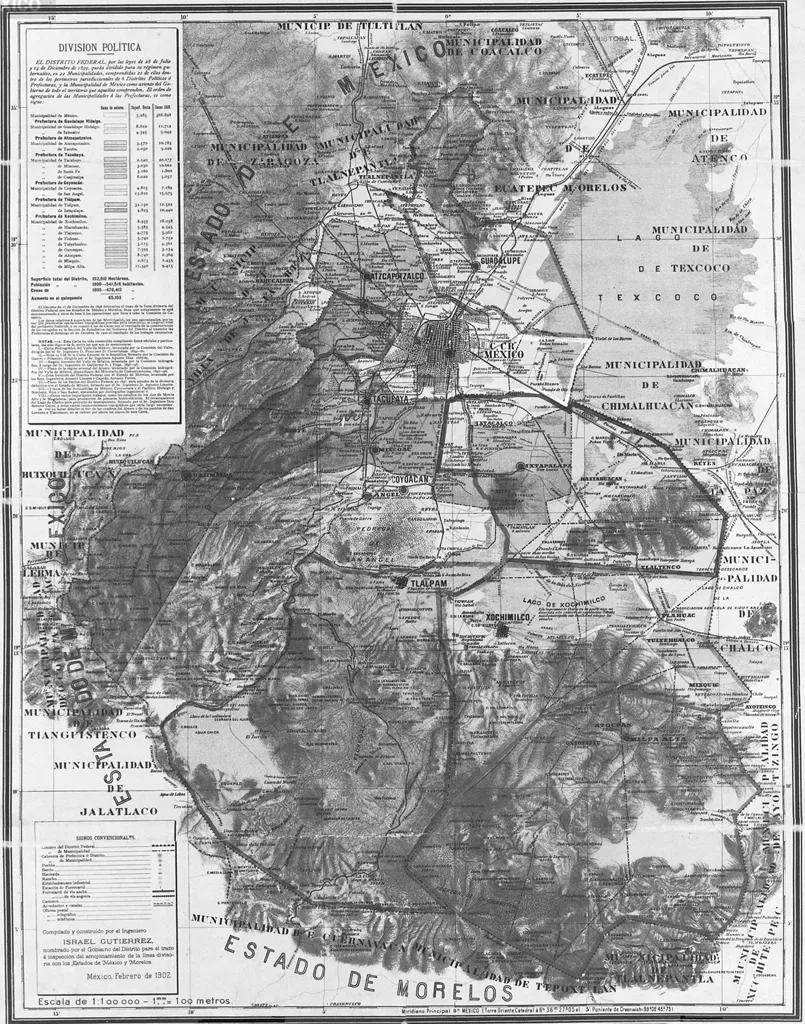

Map, Federal District, Mexico (1902), courtesy Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico.

![]()

1

ON 1910 AND THE CITY OF THE CENTENNIAL

On 1910 and the city of the centennial or on how Mexico City was lastly transformed by the utopia of an ideal city conceived for the 1910 celebration of Mexico’s independence. Thus, after short introductory remarks, the essay provides a postcard of the entire celebration for the reader to grasp what the Centenario was about. Then follows a brief explanation of the three main utopias epitomized by the centennial city—modernization, nationhood, and cosmopolitanism. The essay then walks the reader through three imaginary tours to the centennial city: the first walks the streets, avenues, and monuments; the second through the history, and the third over the styles epitomized by those stones and pavements. In concluding, the essay briefly contrasts the centennial city—a supposed paradise of, as it were, old-regime-ness—with the first vista of the new revolutionary city that emerged out of the 1910 Revolution, namely, the 1921 celebration of the consummation of Mexico’s independence (1821) in the city.

1910 is for us, twentieth-first-century observers, not just another year. It is a year with weighty historical connotations. It is the year around which “human character changed,”1 and it is also, of course, the year of the first massive popular revolution of the twentieth century: the Mexican Revolution. The end of an era, we now know, was then nearer than ever before. Mexico’s 1910 was not solely the year of the Revolution but, more clearly, the peak of an era, that of Centenarios.

The centennial celebration of Mexico’s independence in 1910 materialized in Mexico City in an extraordinary fashion, producing vistas of the ideals within which the Centenario was conceived. These ideals, though never fully brought to fruition, defined the parameters within which many realities were discussed. It would be an act of faith to declare “real” or “correct” or “popular” those ideals. But to map this celebration in order to simply confront the fake vs. the true cultural geographies of 1910 Mexico City would be an act of faith of a different kind, one resting on the belief of a “genuine” cartography of the city of the Centenario. I simply map the celebration in order to demarcate the parameters of the politically and culturally possible around 1910 and around Mexico City.

El Centenario: A Postcard

1910 was consciously planned to be the apotheosis of a nationalist consciousness; it was meant to be the climax of an era. In many ways, it was.2 It constituted a testimony to the political and economic success of a regime. The Centenario also documented Mexico’s achievement of supreme ideals: its economic and scientific progress as well as its cultural modernism. After all, centenaries, since 1876, were meant to be the sort of “mission accomplished” for national histories in Europe and the Americas.3

As early as 1907, the Porfirian government established the Comisión Nacional del Centenario, which was in charge of staging the luxurious and extravagant commemoration. From 1907 to 1910 this commission received thousands of proposals by all classes and regions for different ways to honor the national past: changes in the names of streets, mountains, and avenues; air shows; new monuments and parks; changes in the national flag, anthem, and other symbols; freedom for political prisoners; and a project for young daughters of the high classes to educate their criadas (maids).4 The Comisión Nacional appointed sub-commissions to evaluate proposals; those made by distinguished members of the political or intellectual classes were often accepted. Accordingly September, the month in which a local revolt in 1810 began what eventually would result in Mexico’s independence, became thirty days of inaugurations for monuments, official buildings, institutions, and streets; thirty days of countless speeches, parties, cocktails, receptions, and dancing fiestas. A national fund was created to collect the contributions of businessmen, financiers, professional organizations, and mutualist societies. By September 1910, Mexico City had acquired the visible and lasting marks of the notions of nation, progress, and modernization that the Centenario intermingled and made visible.

From September 1 through 13, Mexico City saw the inaugurations of a new modern mental hospital, a popular hygiene exhibition, an exhibition of Spanish art and industry, exhibitions of Japanese products and avant-garde Mexican art, a monument to Alexander von Humboldt at the National Library, a seismological station, a new theater in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, primary schools, new buildings for the ministries, and new large schools for teachers. All this was in addition to other events, like laying the cornerstones of the planned National Penitentiary. In addition there were opening sessions of many and varied congresses, such as the 17th International Congress of Americanists, the 4th National Medical Congress, and the Congreso Pedagógico de Instrucción Primaria. And all this was only the first thirteen days of September.

On September 16, 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo began the rebellion that eventually and chaotically led to independence. Consequently, days fourteen, fifteen, and sixteen were, of course, the apotheosis of the entire celebration. The fourteenth, the “Gran Procesión Cívica formada por todos los elementos de la sociedad mexicana” (great civic procession of all sectors of Mexican society) paraded from the Alameda park to the Cathedral, depositing flowers at the graves of national heroes and then marching to the National Palace. On the fifteenth, as in a good dramatic play, the theatrical tension rose with the “Gran Desfile Histórico” (great historical parade): the entire history of the nation on foot, episode after episode; this was a march of the stages of Mexico’s patriotic history as understood by the Porfirian liberal reconstruction of the past. In effect, these were walking chapters of an official history that marched over the chapters of yet another history recorded in the city itself. The new civic parades walked over the routes of all of the city’s well-established religious processions. Accordingly, the parade traversed the chapters of the city as a history textbook—it went from the Plaza de la Reforma, along the Avenida Juárez, and finally to the Plaza de la Constitución.5

On September 15 a number of parties and receptions took place. Fireworks illuminated the city skies and at eleven o’clock that night at the Zócalo, President Porfirio Díaz, in the midst of a popular gathering, rang the bell that Miguel Hidalgo had rung a hundred years earlier. For aristocratic observers la noche del grito was a quasi-tourist portrait of Mexico’s popular fiestas and joy. This was the exotic Mexico that intrigued the world, a version that, rather than compromising Mexico’s cosmopolitanism, made it distinctive: guitars, fiesta, enchiladas, pulque, sombreros. But the night also saw undesired and unplanned popular discontent. Mexican writer and diplomat Federico Gamboa, for instance, described the protests of the followers of Francisco I. Madero, the leader that ignited the Revolution. Gamboa himself accepted the task of concealing those expressions of opposition from foreign observers. In turn, F. Starr—by 1910 an established U.S. anthropologist of Mexico—in the violent year of 1914 recalled the celebrations as bombastic self-delusions, as was to be expected from anyone writing about the Mexico of 1910 in 1914. But the Centenario was far from a Leviathan imposition by a rather weak state; it was chaotic and contested in every detail, but under a great consensual myth: peace.6

September 16, in turn, was the official day of commemoration of Independence. The long-planned monument El Ángel de la Independencia was inaugurated in the Paseo de la Reforma. A military parade went from the Paseo de la Reforma to the National Palace, and at night luxurious dancing parties took place in various official buildings. The celebrations continued until the end of the month. During this time, public parks and grand monuments—such as one for former president Benito Juárez in the Alameda—were inaugurated. In addition a gunpowder factory in Santa Fe, the hydraulic works of Mexico City, the National University, a livestock exhibition at Coyoacán, the Gran Canal del Desagüe, and an extension of the National Penitentiary were all also inaugurated. There were ceremonies to honor the beginning construction of the planned enormous new Palacio Legislativo (Parliament), and of a monument to Pasteur. Extravagant celebrations commemorated Spain’s and France’s diplomatic courtesies: the former returned the personal belongings of the national hero José María Morelos; in turn, France returned Mexico City’s key that was, presumably, stolen by the French invaders in 1862, though, as Federico Gamboa pointed out, Mexico City never had an entrance let alone a key. Finally there was the great Apotheosis of the Caudillos and Soldiers of the War of Independence: a giant altar constructed on the main patio of the National Palace to revere the heroes, to which the entire government, foreign missions, and the elite as a whole paid respects.

The centenary was a fleeting show, but never before had the city been so radically and profusely embellished and transformed in such a short span of time. The remains of the centennial city are still essential components of the city; they still produce the same respectful and consensual effect that, according to the Porfirian lawyer and writer Emilio Rabasa, Porfirio Díaz aroused as the embodiment of the nation. During the Centenario, said Rabasa, “when cheering him [Díaz] in the streets, the people saw not the man full of personal prestige, but instead, recognizing the national flag crossed over the chest of the arrogant old man, they acclaimed the ruler only as the symbol of the enhanced nation.”7 For indeed, the Centenario celebrated a hitherto unknown link between the imagery of the dictator, the idea and experience of peace, the image of the nation, and that of the state. It is impossible to know how different urban dwellers experienced the celebration, but one thing is certain: for good or bad, it was then hard to distinguish between Díaz, peace, nation, and state. This was not because the quartet embodied the “real” Mexico, but because it was the first powerful modern articulation of what Mexico meant. “The only national and patriotic program,” said Porfirio Díaz in 1904, “that the government meant to undertake . . . has been to reinforce peace, to reinforce the links that before only war had the privilege to join, thus making more solid and more permanent the ideals and aspirations expressed—sadly with intermittencies—by the various factions of what is a single and indisputable nationality.”8 In this sense, the celebration is historically telling not as evidence of a “fake” and “elitist” nation (as many historians and commentators have elaborated a posteriori), but especially because it was then the most comprehensive and articulated view of the nation ever conceived. That is why it had a central theme, peace, which then meant of course Porfirio Díaz but much more. That is why the ruins of that fake city were able to become the foundations of new articulations of the nation over the twentieth century.

Mapping the Celebration

In 1910 various ideals of the city overlapped in a limited space and time. One was the ideal of modernization, understood as harmonious economic and scientific development, as well as progress. The best embodiment of this ideal was the modern capital city, whereby Mexico City or any other capital could contain the proofs of a nation’s pedigree: economic prosperity and cultural greatness encompassing sanitation, comfort, and beauty. Second, there was the ideal of a long-sought coherent and unified concept of nation; that is, the need for consolidating in chorus as a nation and as a state. The particular epitome of such an ideal was the capital city understood as a textbook of civic religion; a story-telling city that through streets and avenues, monuments, and planning of public and private spaces narrated to the city dweller the nation and the state as a unique local tale, but also as an echo of a larger historical process. Third, there was the modern ideal, inseparable from the other two, of a cosmopolitan style. By the last part of the nineteenth century the quintessential incarnation of the cosmopolitan ideal was a Paris- or Vienna-like city. In the early twentieth century it was impossible for the capital of both a modern nation and a modern state to remain oblivious of its reflection of major late nineteenth-century capital cities—then in constant construction and reconstruction—such...