![]()

CHAPTER 1

In the Beginning—A Tour

Meg’s day at Overbrook Hospital begins early when she is coming off overnight call.1 I meet staff chaplain Meg, in her sixties, wearing street clothes and serious shoes, and carrying a binder overflowing with papers, and Daniel, a Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) student, at 6:30 a.m. on a summer morning in the chaplaincy staff room. Looking remarkably rested for having slept on a hospital cot, Meg says good morning to me before finding scissors to cut today’s Communion list into sections. Spending the night at the hospital is like being on a red-eye, she tells me as she cuts. The night was quiet, though. She was not paged to any deaths or code blues—called when a person’s heart stops—and actually got some sleep. “I think this is the only hospital in the city that has in-house 24/7 chaplain coverage,” she says as she files the lists for the Eucharistic ministers who will deliver Communion to Catholic patients later in the day. Gathering up her binder, she gestures for Daniel and me to follow her to the preoperative surgery unit, where she will begin her morning rounds.

Patients coming into the hospital for same-day surgeries, Meg explains on the way, wait here until their operating rooms are ready. We go through double doors and into a large, open room divided into cubicles with curtains. Everything—hospital gurneys, chart racks, machines—is on wheels. About twenty patients in hospital gowns, many with family members nearby, sit or lie in their curtained spaces. Physicians and nurses in scrubs move quickly through the unit. Stopping in front of a whiteboard by the nurses’ station, Meg turns to Daniel. “I don’t know how other chaplains do this,” she says pointing to the board, “but I like to know the name of the patient first, so why don’t you take that column and I’ll take this column.” Medical staff members are often with patients, so the idea is to quickly meet patients and their families before they are wheeled into surgery and not to interrupt any medical staff in the process.

Daniel begins his rounds, and I follow Meg to the first curtained cubicle. She knocks in the air, saying, “Knock knock,” and then enters slowly, greeting the patient by name. “My name is Meg, and I am here from the chaplain’s office,” she begins. “We are coming around this morning to wish people well and see if there is anything we can do for you.” A few people respond quickly, indicating in words or by tone of voice that they do not want a visit, and Meg moves on. Most invite her into their tiny, curtained areas, where she asks about their surgery, their family members, or the anxieties that are often palpable in the small space.

After they chat for a few minutes, she asks patients if they have a religious affiliation they feel comfortable sharing. If the answer is Catholic, as it is most frequently here, she asks patients if they would like to be on the Communion list. She offers kosher food and electric Shabbat candles to Jewish patients. Meg generally closes her short visits by saying, “I would be happy to say a prayer for you if you would like.” Most accept, and she moves in closer, taking the patient and family members by the hand. Standing with an elderly Catholic patient and his family this morning, she prays, “I put my hands on you in the name of God the Father, his Son Jesus, and in the name of the Holy Spirit. Thank you for this day. . . . We ask you to guide the hands of the surgical team and give them the wisdom and resources they need. . . . We seek your healing in body, mind, and spirit.” Later, when I ask more directly about these prayers, Meg tells me that she mentions Jesus more often when praying with African American and evangelical Christian patients. She rarely prays with Jewish patients, both because they do not have a strong tradition of public prayer and because some feel uncomfortable, thinking she is trying to convert them—something her professional code of ethics strictly forbids.2

I think of the visible ways that Chaplain Meg prays with patients a few weeks later as I sit in a conference room by the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at nearby City Hospital. Christina, a young NICU nurse, is talking with me about prayer. In her twenties, Christina wears scrub pants and an NICU sweatshirt, and seems to exude positive energy. Like Meg, she prays publicly with patients and families, though usually only if the unit chaplain is not available. “Different times in the middle of the night,” she explains, “when the chaplain had not gotten here yet and the baby is dying—we’ve [the nurses] been told that we are instruments of healing, and we’ve actually taken water and blessed it, and blessed the baby ourselves at four o’clock in the morning when a baby has passed away.” Thinking of a specific situation, she continues, “One time in the middle of the night I remember a couple of the [Catholic] nurses, three of us, just started saying the ‘Our Father,’ ‘Hail Mary,’ and the ‘Glory Be,’ and we just prayed over the water and did the sign of the cross and just put it on the baby—you know, head, heart, side, side.” She gestures, crossing herself as she speaks.

In addition to the visible ways that Christina prays in the intensive care unit, she also prays for her patients in less visible ways. While commuting home after a tough day, she talks to her mother, who, in turn, calls Christina’s grandmother. “My grandmother has this religious candle in her kitchen that has pieces of tape with pieces of paper with every person that she’s praying for. And at the bottom of the candle there is a paper for all of the babies in the NICU, . . . and it is lit most times during the day but specific times when babies are not doing really well at all, I’ll call mom and say, ‘Have Nana light the candle,’ and she will.” When caring for a particular long-term patient, Christina started a prayer circle with a few other nurses and their families: “We told the family [of this patient] that not only us but our relatives, our families, are praying for the baby as well, because our families are as much a part of this as we are.” When her family members ask how they can help with her work, Christina tells them to “say a prayer” just as she does privately for all of her patients—regardless of how they are doing—every day.

. . .

Prayers offered—visibly and invisibly—by Meg, her chaplain colleagues, Christina, and other intensive care nurses are one way that religion and spirituality are present at Overbrook and City Hospitals. The hospital chapel, prayer book, questions asked at admissions, and conversations among patients, family members, nurses, and doctors—especially around end-of-life issues—are others, not just at Overbrook and City Hospitals but in large academic medical centers across the country. This book is about how religion and spirituality are present in formally secular hospitals.3 It is about the public and not so public forms religion and spirituality take in medical settings, the reasons they take these forms, and the ways staff members act around them in their daily work.4

The questions I address here are just one aspect of growing public attention to religion, spirituality, prayer, health, and medicine. Time magazine’s February 23, 2009 cover story, “How Faith Can Heal,” reflects other questions and is the most recent in a string of magazine covers with headlines like “The God Gene,” “The Power of Prayer,” and “God and Health: Is Religion Good Medicine? Why Science Is Starting to Believe.”5 Related news articles are on the rise, including recent reports about parents withholding children’s medical treatment on religious grounds, religiously infused debates about abortion in national health-care reform, and public discussions of stem cells and the rights of conscience for health-care providers.6

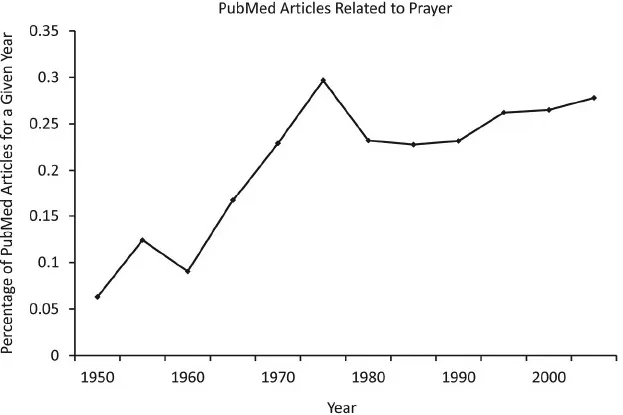

Academic research about the relationship between religion and health is also increasing, especially since 1990. The number of scholarly articles about religion/spirituality and prayer catalogued in PubMed, the main biomedical research database, increased significantly between 1990 and the present, as shown in figures 1.1 and 1.2.7 Many of these studies ask whether personal religion or spirituality—measured in terms of beliefs, affiliations, and behaviors—influences health. The press picks up positive findings and spreads them under headlines like “Is Religion Good for Health? Researchers Say Amen” and “Dose of Religion Tied to Good Health in North Carolina.”8

FIGURE 1.1 Fraction of all articles catalogued in PubMed that have derivations of the terms religion or spirituality in any search field, over time.

FIGURE 1.2 Fraction of all articles catalogued in PubMed that have derivations of the word prayer in any search field, over time.

Also in recent years, university centers like the George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health (GWish) and the Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health at Duke University opened to support research and help new generations of health-care providers be more aware of religious and spiritual issues.9 For the past several years the Department of Continuing Education at Harvard University has cosponsored courses with titles like “Spirituality and Healing in Health and Medicine” (2002) and “Spirituality and Healing in Medicine: Including New Intercessory Prayer Findings and the Concept of Emergence” (2006). Growing numbers of medical schools offer related elective courses as part of their regular curriculum.10 Books with titles like Is Faith Delusion? Why Religion Is Good for Your Health (2009), How God Changes Your Brain (2009), and The Healing Power of Faith: How Belief and Prayer Can Help You Triumph over Disease (2001) are being published alongside more academic books like The Handbook of Religion and Health (2001) and popular books for people struggling with specific health conditions, such as Everyday Strength: A Cancer Patient’s Guide to Spiritual Survival (2006) and The Bible Cure for Heart Disease (1999).

Some health-care providers, scholars, and journalists praise growing relationships between religion, spirituality, and medicine. Others are more skeptical. Columbia University’s Richard Sloan is among the skeptics. Studies that show positive relationships between religion and health, he argues in his book Blind Faith: The Unholy Alliance of Religion and Medicine, are frequently flawed and may harm patients.11 In that book and on op-ed pages and in news magazines, Sloan frequently spars with Harold Koenig, a physician who directs the Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health at Duke University, as well as other prominent advocates of positive relationships between religion and health. They argue about what roles religion and spirituality should play in health care through interactions between patients, physicians, and other staff. Such questions are no less complex than those about the appropriate place of religion and spirituality in public education or politics and may provoke even more controversy, given the life-and-death issues potentially at stake.

Despite the prevalence of research about religion’s effects on health and the veracity of related debates in health care, participants rarely pay much attention to how religion and spirituality are actually present in the day-to-day workings of health-care organizations. Physicians and pundits spend more time arguing about whether patients want their physicians to inquire about their religious and spiritual backgrounds or pray with them than they do actually listening to how the topics come up in physicians’ offices.12 People argue about the morality of public funding for abortion or euthanasia more than they visit health-care organizations or hospices to observe how religion or spirituality actually influences the work of staff and the decisions made by patients and families.

Overshadowed in heated public debates about religion, spirituality, and health—in other words—are the voices of Chaplain Meg, Christina the intensive care nurse, and other health-care workers across the country who see religion and spirituality in their daily work. I take you inside large academic hospitals in this book to show how these people understand religion and spirituality and how they see them actually present in day-to-day events at these hospitals. Unlike the flashy, romantically infused hospital scenes in ER, Grey’s Anatomy, and other popular television shows, this book focuses on the ways religion and spirituality are evident in the architecture of hospital buildings and in the daily routines of hospital life.

This “on-the-ground” approach to religion and spirituality in hospitals is essential for historical and contemporary reasons. Religion has played an important role in the history of American hospitals. Many of the nation’s first hospitals were started by religious organizations, and religion shaped hospital expansion in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. While scholars have written about Catholic and Jewish hospitals, some of which have closed or become secularized in recent years, almost nothing is known about how religion informs daily work in secularized hospitals or others founded as secular organizations.

Such questions are especially important, given that the Joint Commission, which sets policies for health-care organizations, has called on all hospitals to address the religious and spiritual needs of patients since 1969. The 2010 guidelines stipulate that hospitals are to respect “the patient’s cultural and personal values, beliefs, and preferences” and accommodate “the patient’s right to religious and other spiritual services.”13 The Joint Commission singles out particular groups of patients for spiritual assessment, including those dealing with the end of life, alcohol and drug abuse, and emotional and behavioral disorders. The commission also says that hospitals are also to consider spiritual issues when making decisions about food, education, and training for staff.

While stipulating that hospitals must respect, accommodate, and in some cases gather information about spirituality from patients, Joint Commission guidelines have never stipulated how hospitals are to do so. Little is known about how these guidelines evolved and how hospitals try to meet them in the context of America’s religious diversity. According to the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), 25.1% of Americans are Catholic, 49.5% are Protestant or non-denominational Christians (including 3.5% Pentecostal/Charismatic), 1.4% are Mormon, 1.2% are Jewish, and less than 1% are Buddhist or other eastern religions or Muslim. Just over 1% reported being members of other religions. Fifteen percent said they were not religious, and 5% did not respond to the survey question.14 More recent surveys conducted by the Pew Forum show that many people combine ideas from a range of religious and spiritual traditions.15 Scholars and health-care providers have yet to understand how hospitals respond to such diverse beliefs and practices as they strive to meet Joint Commission guidelines.

In addition to historical and policy motivations, it is important to understand how religion and spirituality are present in hospitals because the topics are important to many in hospitals—pati...