![]()

PART I

The Era of Middle Eastern Dominance to 500 B.C.

![]()

CHAPTER I

In the Beginning

In the beginning human history is a great darkness. The fragments of manlike skeletons which have been discovered in widely scattered parts of the earth can tell us little about the ascent of man. Comparative anatomists and embryologists classify the animal species Homo sapiens among the primates with apes, monkeys, and baboons; but all details of human evolution are uncertain. Shaped stones, potsherds, and other archeological remains are sadly inadequate evidence of vanished human cultures, although comparison of styles and assemblages, together with the stratification of finds, allows experienced archeologists to infer a good deal about the gradual elaboration of man’s tool kit and to deduce at least some of the characteristics of human life in times otherwise beyond our knowledge. But the picture emerging from these modes of investigation is still very tentative. Not surprisingly, experts disagree, and learned controversy is rather the rule than the exception.

The various skulls and other bones which have been recovered from scattered parts of the Old World make clear that not one but several hominid (manlike) forms of life emerged in the Pleistocene geological epoch.1 The use of wood and stone tools was not confined to the modern species of man, for unmistakable artifacts have been discovered in association with Peking man in China and, more doubtfully, with other hominid remains in Africa and southeast Asia. Peking man also left traces of fire in the cave mouth where he lived, while in Europe, Neanderthal man knew both tools and fire.

Enough hominid and human remains have been discovered in Africa to suggest that the major cradle of mankind was in that continent.2 The savanna which today lies in a great arc north and east of the rain forests of equatorial Africa offers the sort of natural environment in which our earliest human ancestors probably flourished. This is big-game country, with scattered clumps of trees set in a sea of grass and a climate immune from freezing cold. While weather patterns have certainly changed drastically in the past half-million years or so, it is probable that in the ages when glaciers covered parts of Europe, a shifting area of tropical savanna existed somewhere in Africa, and possibly also in Arabia and part of India. Such a land, where vegetable food could be supplemented by animal flesh, where trees offered refuge by night or in time of danger, and where the climate permitted human nakedness, was by all odds the most suitable for the first emergence of a species whose young were so helpless at birth and so slow to mature as to constitute a weighty burden upon the adults.

Indeed, the helplessness of human young must at first have been an extraordinary hazard to survival. But this handicap had compensations, which in the long run redounded in truly extraordinary fashion to the advantage of mankind. For it opened wide the gates to the possibility of cultural as against merely biological evolution. In due course, cultural evolution became the means whereby the human animal, despite his unimpressive teeth and muscles, rose to undisputed pre-eminence among the beasts of prey. By permitting, indeed compelling, men to instruct their children in the arts of life, the prolonged period of infancy and childhood made it possible for human communities eventually to raise themselves above the animal level from which they began. For the arts of life proved susceptible of a truly extraordinary elaboration and accumulation, and in the fulness of time allowed men to master not only the animal, but also the vegetable and mineral resources of the earth, bending them more and more successfully to human purposes.

* * *

Cultural evolution must have begun among the prehuman ancestors of modern man, Rudimentary education of the young may be observed among many types of higher animals; and the closest of man’s animal relatives are all social in their mode of life and vocal in their habits. These traits presumably provided a basis upon which protohuman communities developed high skill as hunters. As the males learned to co-ordinate their activities more and more effectively through language and the use of tools, they became able to kill large game regularly. Under these circumstances, we may imagine that, even after they had gorged themselves, some flesh was usually left over for the females and children to eat. This made possible a new degree of specialization between the sexes. Males could afford to forego the incessant gathering of berries, grubs, roots, and other edibles which had formerly provided the main source of food and concentrate instead upon the arts of the hunt. Females, on the contrary, continued food-gathering as before; but, freed from the full rigor of self-nutrition, they could afford to devote more time and care to the protection and nurture of their infant children. Only in such a protohuman community, where skilled bands of hunters provided the principal food supply, was survival in the least likely for infants so helpless at birth and so slow to achieve independence as the first fully human mutants must have been.3

How modern types of men originated is one of the unsolved puzzles of archeology and physical anthropology. It is possible that the variety of modern races results from parallel evolution of hominid stocks toward full human status in widely separated and effectively isolated regions of the Old World;4 but the very fragmentary evidence at hand may be interpreted equally well to support the alternative hypothesis that Homo sapiens arose in some single center and underwent racial differentiation in the course of migration to diverse regions of the earth.5

Homo sapiens appeared in Europe only after the last great glacial ice sheets had begun to melt back northward, perhaps 30,000 years ago. There is reason to believe that he came from western Asia, following two routes, one south and the other north of the Mediterranean.6 The newcomers were skilled hunters, no doubt attracted to European soil by the herds of reindeer, mammoths, horses, and other herbivores that pastured on the tundra and in the thin forests which then lay south of the retreating glaciers. Neanderthal man, who had lived in Europe earlier, disappeared as Homo sapiens advanced. Perhaps the newcomers hunted their predecessors to extinction; perhaps some other change—epidemic disease, for example—destroyed the Neanderthal populations. Nor can one assume the absence of interbreeding, although skeletons showing mixed characteristics have not been found in Europe. In the Americas, by contrast, Homo sapiens appears to have entered a previously uninhabited land, although the date of his arrival (10000–7000 B.C.?) and even the skeletal characteristics of the first American immigrants remain unclear.

In regions of the world where the glacial retreat brought less drastic ecological changes, there appears to have been almost no development of tool assemblages.7 Indeed, during the late Paleolithic era, human inventiveness may in fact have been called into play mainly along the northern fringes of the Eurasian habitable world, especially in its more westerly portion.8 Here a comparatively harsh climate and radically fluctuating flora and fauna presented men with conditions to challenge their adaptability. Therefore, the apparent pre-eminence of European Paleolithic materials may not be solely due to accidents of discovery.

Seemingly from the date of their first arrival in Europe, Homo sapiens populations had a much enlarged variety of tools at their command. Implements of bone, ivory, and antler supplemented those of flint (and presumably of wood) which Neanderthal men had used. Bone and antler could be given shapes impossible for flint. Such useful items as needles and harpoon heads could only be invented by exploiting the characteristics of softer and more resilient materials than flint. The secret of working bone and antler lay in the manufacture of special stone cutting tools. Tools to make tools were seemingly first invented by Homo sapiens; and possession of such tools offers a key to much of our species’ success in adapting itself to the conditions of subarctic Europe.9

On the analogy of hunting peoples who have survived to the present, it is likely that Paleolithic men lived in small groups of not more than twenty to sixty persons. Such communities may well have been migratory, returning to their caves or other fixed shelter for only part of the year. Very likely leadership in the hunt devolved upon a single individual whose personal skill and prowess won him authority. Probably there existed a network of relationships among hunting groups scattered over fairly wide areas or, at the least, a delimitation of hunting grounds between adjacent communities. Exogamous marriage arrangements and intergroup ceremonial associations may also have existed; and no doubt fighting sometimes broke out when one community trespassed upon the territory of another. There is also some evidence of longdistance trade,10 although it is often impossible to be sure whether an object brought from afar came to its resting place as a result of an exchange or had been picked up in the course of seasonal or other migrations.

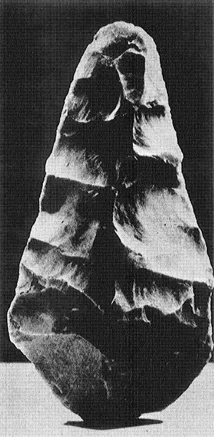

PALEOLITHIC HAND AX

This chipped flint, perhaps as much as 500,000 years old, was found in England on the banks of the Thames. It is 5½ inches long, and the butt is blunt enough to fit into a man’s palm. To a modern eye, the ax seems to have aesthetic as well as utilitarian value. Even if beauty had no place in its maker’s thoughts, we may admire the evident skill with which he chipped the raw stone to produce such a balanced and symmetrical weapon.

Carleton Coon, The Story of Man, Plate V. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Photograph by Reuben Goldberg.

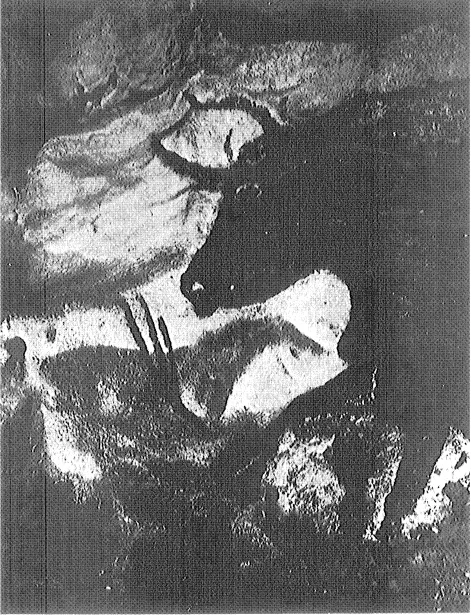

Rude sculpture, strange signs, and magnificent animal frescoes in the recesses of a few caves in France and Spain11 offer almost the only surviving evidence of Paleolithic religious ideas and practices. Interpretation of the remains is uncertain. Ceremonies, very likely ritual dances in which the participants disguised themselves as animals, probably occurred in the dark depths. Perhaps the purpose of such ceremonies was to bring the hunters into intimate relation with their prospective quarry—to propitiate the animal spirits, and perhaps to encourage their fecundity. Possibly caves were used for these rituals because the dark recesses seemed to permit access to the womb of Mother Earth, whence men and animals came and whither they returned; but this is merely speculation.12

The prominence of animal figures in cave art may serve to remind us how precarious was the success of Paleolithic hunters. Their existence depended on game, which in turn depended on a shifting ecological balance. About ten thousand years ago, the glaciers, which for a million years had oscillated over the face of Europe and North America, began their most recent retreat. Open tundra and sparse forest of birch and spruce followed the ice northward, while heavier deciduous forests began to invade western Europe. The herds followed their subarctic habitat northward, while new animals, which had to be hunted by different methods, arrived to inhabit the thick new forests.

About 8000 B.C., therefore, a new style of human life began to prevail in western Europe.13 There is evidence of the arrival of new populations, presumably from the east. Whether these invaders mingled with their predecessors, or whether the older inhabitants followed their accustomed prey northward and eastward, leaving nearly uninhabited ground behind them, is not known.14 In any case, the newcomers brought to Europe some fundamental additions to the Paleolithic tool kit: bows and arrows, fish nets, dugout canoes, sleds, and skis, as well as domesticated dogs, used presumably as assistants in the hunt.

The remains from this so-called Mesolithic period (ca. 8000–4500 B.C.) are on the whole less impressive than those of the Paleolithic age which had gone before. Flints are characteristically smaller; and rock paintings, found mostly in Spain, are less strikingly beautiful. Yet it would be wrong to assume that human culture in Europe had undergone a decline. Even though to the casual eye an arrowhead or a fishhook is less impressive than a harpoon, nonetheless the bow and arrow and the fishing line may be a good deal more effective in winning food. Nor does the fact that almost no traces of Mesolithic religious life survive imply that religion ceased to occupy men’s minds, or even that older religious traditions had been forgotten. We must simply rest in ignorance.

Archives photographiques, Paris.

PALEOLITHIC CAVE PAINTING

This black bull is one of numerous similar figures painted on the walls of a cave near Lascaux in south-central France. It was probably made by Magdalenian hunters who inhabited the region about 16,000 years ago. Why they descended into the bowels of the earth and painted such pictures in the dark depths can scarcely now be known. Accurate observation, seizing upon a characteristic pose even when, as in this example, such details as horns and ears are optically incorrect, lends a remarkable force to these paintings. In a modern observer, this image evokes a sense of animal strength, latent, admirable, yet potentially threatening. Such feelings may actually correspond in some faint measure to the emotional ambiguities which linked ancient hunters to their prey and which such paintings must have somewhow expressed for their makers.

During the Paleolithic and Mesolithic ages man had already become master of the animal kingdom in the sense that he was the chief and most adaptable of predators; but despite his tools, his social organization, and his peculiar capacity to enlarge and transmit his culture, he still remained narrowly dependent on the balance of nature. The next great step in mankind’s ascent toward lordship over the earth was the discovery of means whereby the natural environment could be altered to suit human need and convenience. With the domestication of plants and animals, and with the development of methods whereby fields could be made where forests grew by nature, man advanced to a new level of life. He became a shaper of the animal and vegetable life around him, rather than a mere predator upon it.

This advance opened a radically new phase of human history. The predator’s mode of life automatically limits numbers; a...