![]()

1

The Blindman; or, How to Visit a World Exhibition

The freedom of wandering (libertas vagandi) is divided into two: the movement of the body through different places and the movement of the mind through different images.

—Stephen of Tournai (1128–1203)1

WAKING WAKING

BLIND

IN LIGHTED SLEEPNESS

—Anonymous poem in The Blind Man, NY, 19172

Painting should not be exclusively visual or retinal. It must interest the gray matter; our appetite for intellectualization.

—MARCEL DUCHAMP, 19483

I’m presenting a model of seeing and also facing the fact that my model cannot be a solution but rather a question, maybe a step in a process of some sort of self-realization or self-reflection.

—OLAFUR ELIASSON, artist of The Blind Pavilion, 20034

Here, a “feeling” is not the experience of texture or form through physical contact, but an apprehension of an atmospheric change, experienced kinesthetically and by the body as a whole. This seems to point toward a need for a theory of multiple senses.5

—GEORGINA KLEEGE, “Blindness . . . An Eyewitness Account,” 2005

Blind Epistemology

São Paulo, 1996: You enter a room at the Bienal, installed with seventy-seven seemingly identical boxes on pedestals; a few lids are ajar so you can just see the smoothed edges of abstract-looking sculptures. You want to touch them, but you’re not allowed. Perhaps you get lucky, and a blind person enters who happens to speak your language. She tells you she has been allowed to explore the boxes and read their braille labels—each is a unit in Blind Alphabet by Willem Boshoff, an Afrikaans artist from Johannesburg who also showed this piece at that city’s first biennial (plate 1, fig. 1.22).

Venice, 2005: You are in the twelfth-century Arsenale at this year’s Biennale and come to a large metallic pod in a darkened room. Its iridescent surface has one opening, into which a translucent ladder is set. (The label reads, “Mariko Mori, b. 1967 Tokyo, Wave UFO.”) A white-coated attendant lets you climb the ladder and settle into one of the three reclining seats—but only after swabbing your forehead with alcohol and attaching two electrodes. You lie back and try to follow her instructions to produce calm, meditative, alpha-state brain waves that might harmonize with those of the other visitors in the pod. You want this to work (fig. 6.6).

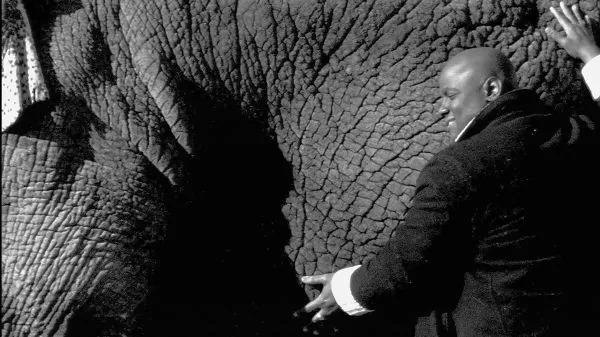

New York, 2008: You enter a small darkened room at the Whitney Biennial and see a gorgeous, high-definition moving image of a person who appears to be blind, feeling his way across the mottled flank of an enormous animal. The camera pulls back, revealing a man and an elephant. Five other individuals approach, encounter the beast, and return to their places in a row of folding chairs; some are exhilarated, but one is afraid. Occasionally, the elephant’s mysterious, coruscating hide fills the screen with slow elephant breaths, so close you could almost touch it. The label reads, “Javier Telléz, b. 1969 Venezuela, lives in New York, Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See, 2007” (fig. 1.1; plate 36).

Kassel, 2012: You’re at documenta 13, and you’ve heard there’s a good piece somewhere on this street; you enter what seems to be an abandoned garage. The room is utterly dark, but you hear people shuffling, breathing. Some begin to make chirping noises or sing bursts of notes; there seems to be some dancing. You discern a gathering rhythm, a beatboxing groove being laid down in syncopated fragments, a riff on the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.” You secretly sing along. Someone in the dark speaks the work’s label: “This Variation, January 2009, Tino Sehgal.” Later you find out the artist was born in London in 1970, and lives in Berlin.

Patterns of visitor desire and global circulation characterize these snippets of contemporary biennial culture; the four narratives also evince a trope of blindness and alternative sensory modes of knowing. In service of what I call blind epistemology (more fragmented and tentative than an epistemology of blindness), these tropes surface a politics of the partial view.

Blind epistemology sets out a framework for this book as a whole. The trope from which it emerges appears in the nineteenth-century reception of the world’s fairs but becomes a full-blown epistemology in the twentieth century, when artists get engaged. The biennial culture that inherits these strategies in the twenty-first century propels contemporary artists’ frustration of everyday vision, soliciting estrangement, visceral experience, and multimodal sensation—all in the name of art. Biennial curators choose such artists because they enact these strategies of refusal: incisions into spectacle, rejections of national posturing, grit in the gears of globalization.6 Contemporary invocations of sightlessness thus have a progressive, critical tenor; they seek to hoist viewers into new economies of experience, against those that are overcapitalized or touristic.

The “Hypothetical Blind Man” was not always a positive tool to critique “ablist” assumptions, as disability theorist Georgina Kleege notes.7 This introductory chapter will track the blindman trope8 in Western culture, flagging a surprising intersection with international art exhibitions and tracing a genealogical legacy for the contemporary biennial. I will argue that the figure of the blindman, and the tools artists wrest from this tradition (blind epistemology), become crucial to the critical workings of a now global art.

What is a blindman’s world picture? For over two hundred years, world’s fairs (and their biennial heirs) have dazzled spectators with metaphorical and material world pictures. Historians of these events risk reinscribing the technospectacular sublimity organizers intended. That is why the periodic emergence of blindness—as a philosophical trope, an actors’ category, and a tactic of contemporary artists—is so noteworthy. The blindman demands a rethinking of how we form knowledge, a skeptical tradition that usefully accompanies these exhibitionary forms. Precisely because tropes of blindness drove philosophies of Enlightenment, and fairs put Enlightenment philosophy (as well as its presumptions and prejudice) into material form, we need this past for any history from the present.

This book’s chosen present is constituted by biennials’ world pictures. Biennials now take place in some two hundred cities on every continent, looking back to the world’s fairs and forward to the art fairs they have spawned.9 As yet, no histories trace the precise relays between these festal forms. How did the world’s fairs serve art? Why was the biennial form invented? How did both form their publics? This book argues that the fairs are deeply significant for an understanding of the biennial form, producing the conditions of possibility for art to become an international, and now a global, semiotic.

Both biennials and fairs implicate a larger public than art history traditionally encounters. Consider: A young Polish-American mathematician with a bilingual family wants to go to the 2013 Venice Biennale “because it’s fun” and showcases art from places he will never visit. An established New York artist (born in Britain) dourly criticizes “biennial artists” but wishes he was one; another, living in Berlin (also born in Britain), surely is, producing work more comfortable in such settings than in the museum. A Swedish curator (educated in New York) uses the biennial like a laboratory, posting notes about his process in the installation. These interventions in a largely Euro-American art world (where I am positioned to encounter them) reveal that biennials forcefully mold both art and its history. As a heuristic, “the biennial” can reveal intersections of state power, municipal ambitions, artistic intention, curatorial tactics, and public desires for a globalism that is not globalization. The concept of “critical globalism” is introduced in this book: once artists began to generate conscious tactics for their insertion into the fairs’ world pictures, such tactics were available to join conceptualism and institutional critique during the epoch after World War II, contributing to a “globalism” in art that critically reflects on globalization, often through a multisensoriality localized in the body.10

Reading spectacle against the grain, this and the six chapters that follow mine layers of historical data, visual materials, artworks, and criticism to form interlocking narratives: on how to turn from spectacle within the world picture (1), on publics and artists activating world’s fairs against their organizers’ ideologies (2), on the first biennial and the national/international circuitry it put into place (3), on the importation of the biennial model to the new world and the frictions that ensued (4), on the emergence of the transnational curator as a neutralizer of such frictions (5), on the emergence of an “aesthetics of experience” (6), and finally, on artists’ tactics of critical globalism against globalization (7). I attend to the world pictures that these exhibitions construct, tracing networks of national pavilions, state and corporate sponsors, city branding, global marketing, and the politics of prizes; the trope of blindness checks these vast apparatuses. Note that blindness is unlikely to occur in the prose of municipal boosters, state administrators, or corporate funders—it is the curators, artists, and attendees who take up the blindman trope. They bring Classical and Enlightenment references into the twenty-first century, where they use the critical probe of blindness like an Archimedean lever for extracting multisensory experience from the maws of spectacular excess. Learning from disability theorists, I argue that those who bring blindness into the world of spectacular exhibitions do so to become “whole human beings who have learned to attend to their non-visual senses in different ways.”11 These nongeneric, nonuniversal beings are nonetheless producing a resonant common sense.

The blindman trope leverages understandings of the Western obsession with visuality and “perspective.”12 It also opposes the singular “world picture” bequeathed by philosopher Martin Heidegger, mindful of instrumentalizing world’s fairs (1937’s was particularly problematic) and campaigns against “degenerate” art (an international exhibition also mounted in 1937). In a crucial paper on “the age of the world picture” that he began in 1935 to give at the Paris world’s fair (but ended up delivering in 1938 Germany), Heidegger upended notions of Weltanschauung (a “world view” that could be held by any human in a given historical period), rejected Wilhelm Dilthey’s Weltbilder (the different “world pictures” held by various communities), and insisted instead on a historical threshold—Die Zeit des Weltbildes. In this argument, modern times produce a metaphysical “enframing” of the world, allowing it to be possessed as a single picture or concept. Heidegger’s dark vision saw one synchronized representation producing the world-as-object and facilitating human “mastery over the totality of what-is.”13 That moment will be historicized here (with Heidegger confronting French philosophy at the fair), and confounded by contemporary art. Against a hegemonic world picture, I find evidence for competing, multiplied, and critical world pictures, enmeshed in the complexities of the Anthropocene. Linked to our desires as global citizens and taking unruly form in bodies only partially colonized by ideologies imposed from above, our world is no longer a picture at all, but a careening event in being and becoming.

Large-scale exhibitions reveal this trajectory with clarity, accompanied by the blindman as an actor’s category and receptive milieu. How does the visitor navigate the massive international exhibition? How does the critic “cover” it? What can the individual artist do to frame a critical position? To take only the examples introduced so far, some artists will be utopian: “Wave UFO believes that . . . as collective living beings [humans] shall unify and transcend cultural differences and national borders through positive and creative evolution” (Mariko Mori).14 Curators might emphasize critique: “If our senses disengage the...