![]()

PART ONE

Two Traditions of Political Ethnography

The chapters in Part 1 trace two broad traditions of political ethnography—a realist and an interpretivist one. Jan Kubik in chapter 1 details some of the principal contributions of each of these two traditions, emphasizing that while political scientists tend to imagine ethnography as necessarily interpretivist, ethnography has been used in a striking variety of ways, even in its “mother discipline” of anthropology. Indeed, Kubik adds a third and more recent tradition—postmodern ethnography—which presents new challenges and opportunities for students of politics.

In chapter 2 Jessica Allina-Pisano provides a series of fieldwork-based vignettes that highlight the value of realist ethnography. Arguing that realist ethnography can provide one way of adjudicating truth-claims and negotiating power-laden situations, she suggests that political ethnographers should not abandon their claims to “small-t” truth; their methods and approaches—among them, their attention to many layers of interpretation that characterize human communities—are in fact uniquely suited to discovering these truths.

In chapter 3 Lisa Wedeen offers an interpretivist understanding of what political ethnography can do, arguing that the ethnographer is well positioned to shed light on “performative practices.” She distances the ethnographic project from the language and conceits of behavioralism, emphasizing that individuals do not simply “behave”; rather, they “practice” in ways that are unique to human beings. Moreover, people “perform”—that is, their perspectives are not pristinely isolated and waiting to be discovered by the researcher; rather, they are in motion and emerge in the process of human expression.

![]()

ONE

Ethnography of Politics: Foundations, Applications, Prospects

JAN KUBIK

Today’s political science is a massive, multistranded research enterprise whose complexity defies succinct characterization. It is therefore difficult if not impossible to provide a simple and concise answer to the question, “What is the use of ethnography for political scientists?” It depends on the aim of the research project, the specific ontological assumptions about social/political reality, and the particular conception of ethnography. Since it is impossible to consider all possibilities in a single chapter, I delimit the scope of my remarks to two problématiques that are central to the comparativist enterprise: the significance of the cultural aspect of social reality and the consequences of the recent turn from macro- to micro-levels of analysis (Elster 1985; Geddes 2003). I focus discussion on the subfield of comparative politics, since it has been the site of most ethnographic work conducted within political science. It is also the subfield I know best.1

The relative utility of ethnography is closely related to our understanding of politics. March and Olsen (1989, 47–48) typify a commonplace, materialist-institutional understanding by suggesting, “The organizing principle of a political system is the allocation of scarce resources in the face of conflict of interests.” This is a time-honored way of thinking about politics, for, as March and Olsen observe, “a conception of politics as decision making and resource allocation is at least as old as Plato and Aristotle.”

Yet March and Olsen are keenly aware of a significant shortcoming of this conception: “Although there are exceptions, the modern perspective in political science has generally given primacy to substantive outcomes and either ignored symbolic actions or seen symbols as part of manipulative efforts to control outcomes” (1989, 47). Not all politics can be reduced to competition over material resources; indeed, much of it concerns the struggle over collective identity, including often deadly contests over the meaning of symbols signifying this identity. Dirks, Eley, and Ortner (1994, 32) develop this thought further:

Politics is usually conducted as if identity were fixed. The question then becomes, on what basis, at different times in different places, does the nonfixity become temporarily fixed in such a way that individuals and groups can behave as a particular kind of agency, political or otherwise? How do people become shaped into acting subjects, understanding themselves in particular ways? In effect, politics consists of the effort to domesticate the infinitude of identity. It is the attempt to hegemonize identity, to order it into a strong programmatic statement. If identity is decentered, politics is about the attempt to create a center.

Such centers emerge and disintegrate as a result of specific actions by concrete actors who propose, disseminate, and interpret cultural meanings encoded in a variety of symbolic ways. To study such processes, political scientists—at least those who recognize that any attempt to propose and propagate a vision of collective identity, and thus any “cultural” effort whose aim is endowing human (particularly collective) action with meaning, is par excellence political—must move beyond the materialist-institutional perspective and employ a symbolic-cultural approach.2 And within such an approach “the researcher should ask whether the theory is consistent with evidence about the meanings the historical actors themselves attributed to their actions” (Hall 2003, 394). For researchers who embrace ontologies that include the “meaningful” layer of reality, ethnographic approaches emerge as promising tools for studying politics.

If we understand politics as, in some important measure, locally produced, we again might turn to ethnography. Indeed, attention to the microlevel of analysis constitutes an important trend in today’s study of politics (Geddes 2003). Game-theoretic ambition to develop a concise theory of politics (Bates et al. 1998) and a more sociological quest to identify micro- or meso-level mechanisms governing social and political life (Tilly 2001) share an assumption that progress in the social sciences is more likely when our analytic gaze is focused on the details of concrete interactions rather than the workings of “large” structures. Thomas P. O’Neill Jr.’s memorable quip that “all politics is local” captures this idea.

This turn to the local coincides with renewed interest in observing “actual” human behavior: students are increasingly admonished to focus on the “real life” interactions of people in “real time,” rather than on interactions of variables in abstract theoretical spaces.3 Hall captures this perspective:

The systematic process analyst then draws observation from the empirical cases, not only about the value of the principal causal variables, but about the processes linking these variables to the outcomes. . . . This is not simply a search for “intervening” variables. The point is to see if the multiple actions and statements of the actors at each stage of the causal process are consistent with the image of the world historical process implied by each theory. (2003, 394)

This attention to the symbolic-cultural and to the local, micro-scale, and “actual” should make political scientists hungry for more ethnography, a research tool well suited for addressing these emergent concerns.

But we need to pause to consider the intellectual, philosophical, and epistemological origins of the long and tangled traditions of ethnographic inquiry before we can appreciate ethnography’s potential value for the study of politics.

The Promise of Ethnography

Most writers posit participant observation as the defining method (or technique) of ethnography (Bayard de Volo and Schatz 2004, 267; Tilly 2006, 410). Below I investigate the usefulness, if not indispensability, of ethnography for studying a reality that is construed as meaningful (“ideal”), processual (“diachronic”), and interactive. Suffice it to note here that ethnography’s usefulness for studying “constructed” realities has been demonstrated in sociology (where it serves as an auxiliary tool) and anthropology (where it is the principal tool), and should thus be examined by political scientists, particularly comparativists, who are often admonished to take culture seriously (Norton 2004; Chabal and Daloz 2006; Harrison and Huntington 2000; Rao and Walton 2004).4 In sociology, it supplements various interpretive techniques (for example, content or textual analysis) in studies that treat cultures as assemblages of (broadly understood) texts; in anthropology, it is indispensable for studying culture in action.

But ethnography obviously can be and has been employed by more positivistically oriented researchers. It is thus imperative to outline the differential uses of ethnography in positivistic and interpretivist research programs. Let us begin in ethnography’s “maternal” discipline, cultural/social anthropology. To be sure, culture is not the only object of this discipline, which is composed of several, partially separate intellectual traditions, to some extent overlapping with “national” schools.5 An exhaustive discussion is beyond my scope, but it is worthwhile to highlight one distinction: while the “British” have developed social anthropology, the “Americans” tend to practice cultural anthropology. Beyond semantics lie fundamental ontological, epistemological, and methodological issues. In a nutshell, while the “British” generally tend to focus their efforts on studying social structures and their “political” dimension (initially in non-Western societies), the “Americans” tend to construe the object of their studies as culture(s) and the multiple ways in which culture interacts with power. These different definitions have consequences for the nature of specific projects, their conceptualizations, and methodologies. But at the same time these two traditions have something in common: they both approach politics as an aspect of social relations that needs to be studied in practice, in statu nascendi, through extensive fieldwork centered on (preferably long-term) participant observation.

What ethnographers observe (via participation) depends on the particular school or research tradition. By and large, while “British” lenses “detect” structure, “American” ones are fitted for studying culture. Significantly, both “structure” and “culture” can be and often are these days defined in a constructivist manner. It is enough to consider Giddens’s theory of structuration or Bourdieu’s theory of practice—both par excellence constructivist conceptions of social structure. Moreover, at least since the wave of postmodern critiques, we know that “objects” of study do not exist out there, in an “objective reality,” ready to be “discovered”; rather, they are coconstituted by the two (or more) participants in a research interaction.

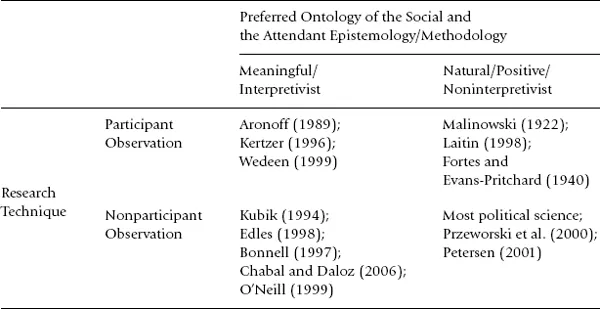

Ethnography as a method (participant observation), therefore, is not limited to the study of culture. Just as many interpretive studies of politics rely on participant-observation, noninterpretive studies use the same method (for example, studies of organizational structures, informal networks, or economic exchanges). At the same time, not all interpretive studies of power and politics are ethnographic (Bayard de Volo and Schatz 2004, 267). In fact, most are not. Table 1 illustrates these distinctions, based on examples drawn mostly from comparative studies of politics.

Most research in political science is based on a naturalist ontology of the social and does not rely on participant observation; the work of Przeworski and his collaborators (2000) on the relationship between economic development and the survival of political regimes is exemplary. Such work is also practiced to great effect in the broadly defined area of “political culture”; consider the large-n studies of Inglehart and his collaborators who survey “values” of the world’s population. Also, most work in game theory is noninterpretive, as it is built on deductively derived models of purportedly universal motivation mechanisms. Some game-theoretic work is sensitive to local contexts and is “ethnographic” in its tenor, although it does not typically use participant observation. (Petersen’s work, for example, deals with past events, as I discuss below). The second category features naturalist/positivistic works that rely on participant observation but do not provide interpretive accounts of the social worlds actors live in. Much of classical British social anthropology belongs to this category. Most influential works in comparative politics that rely at least partially on participant observation belong to the naturalistic, noninterpretive genre, though some—such as Laitin’s influential 1998 study—are close to the boundary between interpretive and noninterpretive types of work.

Table 1

The third type includes works that are interpretive but do not use participant observation. Bonnell’s (1997) analysis of Soviet posters as tools of power, Edles’s (1998) work on the symbolic dimension of Spanish democratization, or my own study (Kubik 1994) of Polish Solidarity’s symbolic challenge to the hegemonic power of the Communist Party belong to this type. Finally, works belonging to the fourth type combine interpretive epistemology with participant observation as the main method. Consider Aronoff’s (1989) study of the inner workings of the Israeli Labor Party, Kertzer’s (1996) detailed reconstruction of the Italian Communist Party cell’s operation in a local setting, or Wedeen’s (1999) analysis of everyday, counter-hegemonic challenges to Hāfiz al-Asad’s power in Syria.

To summarize: as a method,6 ethnography is used to study culture (meaning systems) or other aspects of the broadly conceived social, such as economy, power (politics), or social structure. Its essence is participant observation, a disciplined immersion in the social life of a given group of people. Ethnography is sometimes erroneously equated with (1) in-depth interviewing (as opposed to administering surveys); (2) case studies (as opposed to large-n statistical studies); (3) process tracing (as opposed to finding correlations); and (4) interpretation of meaning (as opposed to the “naturalistic” study of “objective” social facts). Studies based on these four methods are not necessarily ethnographic; they become so when they rely on participant observation of considerable length.7

An answer to the question “What is ethnography good for (in the study of power and politics)?” depends not only on the definition of ethnography, but also on the conception of a discipline (its ontological and epistemological assumptions) within which it is defined and practiced. Because the track record of ethnographic work is more robust in anthropology than in political science, let me examine what it has contributed to each of three broad traditions of political anthropology: positivistic, interpretive, and postmodern.8

Ethnography in Positivistic (Political) Anthropology

In this section I take stock of the contributions that traditional, positivistic ethnography has made to the study of power. I do so to emphasize a central point: ethnography can benefit positivistic research agendas at least as well as it can contribute to interpretive ones. Thus, as Allina-Pisano shows in chapter 3, ethnography has a long tradition of working in a “realist” vein.

Political anthropology is a subdiscipline with a distinguished tradition of realist inquiry. Many illustrious nineteenth-century scholars (most prominently Maine, Spencer, Marx, Morgan, and Tylor) studied non-Western political systems and, particularly, their evolution.9 They can be seen, therefore, as precursors or early practitioners of the discipline. But the modern field of political anthropology is often said to have emerged with the publication in 1940 of African Political Systems, edited by M. Fortes and E. E. Evans-Pritchard. All studies reported in that volume were based on extensive ethnographic fieldwork, but, by contrast to today’s anthropologists—who would emphasize the cultural specificity of each case—the editors made an explicit effort to strip all social processes of “their cultural idiom” and reduce them “to functional terms” to generate comparisons and arrive at generalizations (quoted in Vincent 1990, 258). At the time of the volume’s publication, anthropology (including political anthropology) was still predominantly characterized by its focus on non-W...