eBook - ePub

Community Health Equity

A Chicago Reader

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Community Health Equity

A Chicago Reader

About this book

Perhaps more than any other American city, Chicago has been a center for the study of both urban history and economic inequity. Community Health Equity assembles a century of research to show the range of effects that Chicago's structural socioeconomic inequalities have had on patients and medical facilities alike. The work collected here makes clear that when a city is sharply divided by power, wealth, and race, the citizens who most need high-quality health care and social services have the greatest difficulty accessing them. Achieving good health is not simply a matter of making the right choices as an individual, the research demonstrates: it's the product of large-scale political and economic forces. Understanding these forces, and what we can do to correct them, should be critical not only to doctors but to sociologists and students of the urban environment—and no city offers more inspiring examples for action to overcome social injustice in health than Chicago.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Part I

A Divided City

Health equity means that everyone should have a fair opportunity to live a long, healthy life. It implies that health should not be compromised or disadvantaged because of one’s race, ethnicity, gender, income, sexual orientation, neighborhood, or other social characteristics. Applying an equity lens on health outcomes requires the researcher and the public health practitioner to ask, Who is not thriving? This part of the Reader presents studies that highlight the great neighborhood divides between black and white residents of Chicago and their consequences for health (acknowledging that inequities exist between other racialized groups as well). Ranging from the early twentieth century to the early twenty-first, these readings remind us that, while time has passed, the structural nature of health inequity has not.

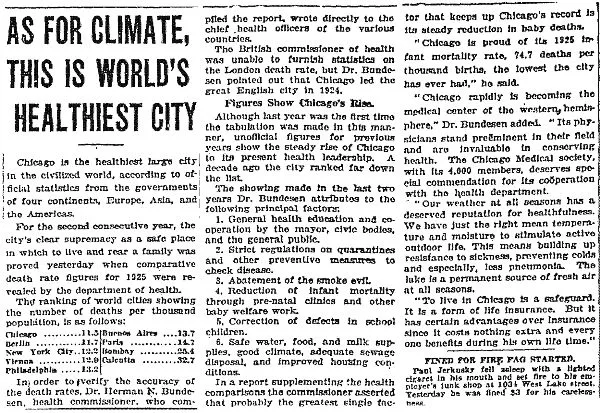

This part of the Reader opens with an article by H. L. Harris, originally written in response to a 1926 Chicago Tribune article proclaiming, “This is World’s Healthiest City” (see figure 2). In one of the first empirical assessments of health inequities in Chicago, Harris provided a striking rebuke to that claim. From a certain perspective, the claim that Chicago was the world’s healthiest city was true. The ranking of world cities with populations of over 1 million inhabitants showed that Chicago’s death rate (11.5 per 1,000 population) was lower than those of Berlin, New York, Vienna, and other cities. Yet Harris argued that this claim was supported only by aggregated data; it was correct only if we ignored the differences in death rates between whites and blacks in Chicago. Looking at death rates for whites and blacks revealed profound differences, with black death rates in Chicago closer to those of residents of Bombay than other American cities. Harris’s analysis is a powerful example of the potential for research to identify and expose otherwise hidden inequities.

Figure 2. “World’s healthiest city”

Source: Chicago Tribune. June 27, 1926.

There are three observations that one can make about this relatively simple analysis and the discussion of it provided by Harris. The first is that inequities can be hidden within aggregated data. Simply reporting an average rate can hide the differences within that average, glossing over the differences that exist in that place.1,2 The second is that the belief that a rising tide of health improvements will raise the health of everyone is, ultimately, incorrect. History has shown that those marginalized in society benefit last and least from technological improvements that have the potential to improve health.3,4 The third is that the public health improvements touted as being responsible for the life span improvement in the first decades of the twentieth century were likely disproportionately extended to the population with the most economic resources, political power, and access to health care—a fact that is as true in 2018 as it was in 1926.

Harris’s work foreshadows many of the studies in this Reader. For example, Harris emphasized the importance of local data, something that the Sinai Urban Health Institute brought to the forefront of health equity work in Chicago starting in the 1990s, exemplified by the work of Ami Shah et al. in part 2 of this Reader. Harris’s analysis of the trajectories of tuberculosis death rates for whites and blacks is not at all dissimilar from more contemporary analyses of breast cancer mortality also shown in part 2 of this Reader by Steve Whitman et al. In addition, his observation of racial segregation in Chicago hospitals is echoed in the work of the Committee to End Discrimination in Chicago Medical Institutions in the 1950s and the Medical Committee for Human Rights in the 1960s, discussed in part 3 of this book. In assembling this Reader, we have been struck by the relevance of Harris’s work—many of the issues he identified ninety years ago remain salient in our city today.

Part 1 highlights contributions from the classic Chicago school of sociology. Robert Faris and H. Warren Dunham apply the concentric zone model of the city developed by Robert Park and Ernest Burgess to the study of mental disorders, examining the geographic distribution of economic wealth and social characteristics, arguing: “The characteristics of the populations in these zones appear to be produced by the nature of the life within the zones rather than the reverse.” Their work is among the earliest and clearest expressions of what we now call the social determinants of health. The community issues that Faris and Dunham discuss remain critical today—from the breakdown of social cohesion to the problematic nature of acculturation to the fundamental social causes of mental disorder. Faris and Dunham “reveal that the nature of the social life and conditions in certain areas of the city is in some way a cause of high rates of mental disorder” (emphasis added).

In Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, St. Claire Drake and Horace Cayton offered a powerful assessment of residential segregation. After documenting the perspectives of community members, Drake and Cayton lay out the health effects of residential segregation—emphasizing that the black tuberculosis rate was five times higher than the white rate and that the black “venereal disease” rate was as much as twenty-five times higher than the white. Perhaps most poignantly, in their analysis of white versus black death rates for tuberculosis, Chicago fared much worse than other major cities in the United States.

We then turn to Abraham’s ethnography of the Banes family in North Lawndale—Mama Might Be Better Off Dead. It is here where the divisions in Chicago became most striking, in an account written fifty years after Drake and Cayton’s work: “The medical and technological might of the [Illinois Medical District] contrasts dramatically with the area around it. Just past the research buildings and acres of parking lots lie some of the sickest, most medically underserved neighborhoods in the city.” Beyond the epidemiological indicators that quantify health inequities in Chicago, Abraham’s qualitative work gives us insight into a world that few health professionals or academics can truly understand. The plight of the Banes family remains representative of a large proportion of the city’s population today.

Part 1 of this Reader concludes with a selection from urban sociology—Robert Sampson’s Great American City. This selection features a walk down Michigan Avenue, starting at Chicago’s Magnificent Mile, a glittering high-priced shopping area bustling with tourists and wealthy residents. Sampson describes the changing landscape of the city as he walks south on Michigan Avenue, leaving high-end shops for single-room occupancy hotels, transitioning from areas of “concentrated advantage” to communities of “concentrated disadvantage” and economic hardship. He observes: “There are vast disparities in the contemporary city on a number of dimensions that are anything but randomly distributed in space.” Tracing the lineage of his work to Black Metropolis, Sampson notes that many of the disadvantaged communities identified by Drake and Cayton in 1945 continue to be disadvantaged today; while some specific communities may change, “the broader pattern of concentration is robust.” In other words, the structural inequality in Chicago communities is deeply embedded in society, affecting populations over generations, and directly causing profound and preventable morbidity and premature mortality.

Together, these selections describe a divided city, a metropolis with deep-rooted and man-made segregation. They illustrate the historical presence of structural violence and how it has worked in Chicago. As you read these texts, we encourage you to consider the following: What are the key elements of social division in these analyses? How do race, class, gender, and place intersect in these cases? To what extent do these selections reflect your experience of Chicago? How has your life been influenced by your city’s social divisions?

References

1. Asada Y. Health inequality: Morality and measurement. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2007.

2. De Maio FG, Linetzky B, Virgolini M. An average/deprivation/inequality (ADI) analysis of chronic disease outcomes and risk factors in Argentina. Population Health Metrics. 2009;7(8). https://pophealthmetrics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-7954-7-8.

3. Farmer P. Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003.

4. Bartley M. Health inequality: An introduction to theories, concepts and methods. Cambridge: Polity; 2004.

Chapter One

Negro Mortality Rates in Chicago

H. L. Harris Jr.

Originally published in Social Service Review 1, no. 1 (March 1927): 58–77.

A recent bulletin by the Health Commissioner of the City of Chicago cites figures showing that for 1925 Chicago had the lowest death-rate of any city of a million or more population, and calls attention to the major factors underlying this enviable record.1

Only a few days after the publication of this article, however, the Commissioner of Health said to the members of the Negro Health Committee of Chicago that the Negro citizens of Chicago had a death-rate more than twice that of the whites and an infant mortality-rate of 118 for Negroes as compared to 71 for whites. He further stated that Negroes have a still-birth rate more than twice as great as that of whites, a death-rate from tuberculosis and syphilis nearly six times as great, and a death-rate from pneumonia more than three times that of the whites. The Co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword, Linda Rae Murray

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. A Divided City

- Part II. The Health Gap

- Part III. Separate and Unequal Health Care

- Part IV. Communities Matter

- Part V. Taking Action

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Community Health Equity by Fernando De Maio, Raj C. Shah, MD, John Mazzeo, David A. Ansell, MD, Fernando De Maio,Raj C. Shah, MD,John Mazzeo,David A. Ansell, MD in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.