![]()

1

Why Do Some Places Generate More Wealth Than Others?

What can people be paying Manhattan or downtown Chicago rents for, if not for being near other people?

ROBERT E. LUCAS

Asking why some places generate more wealth than others is not very different from asking why some people succeed in life while others do not. There are general rules—good health, having loving parents, and growing up in stimulating surroundings—but these alone do not guarantee success and happiness. Individual traits and circumstances count for just as much, if not more. No two individuals are exactly alike. Trying to explain why, within every nation, some places generate more wealth than others is inevitably a balancing act, a constant move back and forth between general laws and particular situations. The quest for grand explanations—and magic recipes—is constantly thwarted by local realities. Simple explanations are the exception, not the rule.

The purpose of this chapter is to bring that message home. I wish to give the reader a sense of the diversity of reasons that explain why some places grow and prosper compared to others. Local success stories abound, as do stories of decline, and chance is all too often the deciding factor. However, I also wish to give the reader a foretaste of the laws of economic geography from which it is impossible to escape. If we pay attention, patterns do emerge underneath the apparent chaos of different destinies, whether they concern big cities, regions, or villages.

Before continuing, a few words are in order on my use of the terms wealth and growth. All throughout the book, wealth is used as shorthand for material welfare or, in more technical terms, as the equivalent of income or product per person, in cases where income data are not available.1 I shall use these terms interchangeably. Regional growth, as used in this book, has a double meaning: growth both in material welfare and in population numbers. In regional economies, the two are generally associated. In open societies, populations will, as a rule, migrate towards places, communities, and regions where incomes are higher.2

But why should some places generate higher incomes than others in the age of the Internet, e-mail, and cell phones, in which we are said to have finally vanquished the monster of distance and broken the chains of geography?

Places in a Shrinking World

I turn on my computer and am instantly in touch with almost every corner of the planet. From Montreal—where I am sitting—the price of a telephone call to other parts of Canada is hardly worth mentioning. And the price continues to fall and will soon approach zero. Airplanes carry me to other cities in North America and Europe in a matter of hours. At my local market, day-fresh blueberries from New Jersey and British Columbia are currently for sale, displayed alongside mangoes from Mexico and oranges from South Africa. Yes, the world is shrinking, certainly with respect to the speed at which information travels. Ranchers in Montana have instant access to beef price quotes in Chicago. Bankers in London are able to follow the latest developments on the oil rigs off Scotland as they happen. The IT (information technology) revolution is transforming our world. It no longer matters where one is. All places are equal... or are they?

One of the paradoxes of the IT revolution is that place now matters more. At the end of this book, the reader will hopefully understand why. I could just as well have called this book The Wealth and Poverty of Places; but somehow that doesn't have the same ring as The Wealth and Poverty of Regions. The idea conveyed in both cases is that we are dealing with places, communities, localities, towns, cities, urban areas, and regions (the list of labels is almost endless) whose boundaries are not always clearly defined and which are confined within a nation. The U.S., Britain, India, China, etc. are patchworks of communities, places, and regions of varying sizes, names, and shapes. Upstate New York is a region, but it is also a place, and some might say that it is a community too. This definitional fuzziness should not bother the reader. Places can have many names and shapes. In more technical jargon, the objects of study are sub-national spatial units, be they villages, towns, cities, or regions. This book attempts to explain differences in economic fortunes within nations—between the various places that make up a nation—and not between nations. Explaining why the U.S. or Britain is richer than, say, Nigeria is not at all the same thing as explaining why certain places in the U.S. or Britain are richer—or growing more rapidly—than other places in the U.S. or Britain.

Let us return to the IT revolution. If place no longer mattered, differences in economic fortune within nations—between different places—should have disappeared (or at least be in the process of disappearing), certainly within the world’s more economically advanced nations. The evidence tells the opposite story. In United States—arguably the world’s most mobile society with a long history of free movement and exchange between places—income differences between places are far from insignificant. Average personal incomes in 2006 in the three poorest counties, Loup, Nebraska, and Ziebach and Buffalo in South Dakota, were respectively, $9,140, $11,381, and $12,471 compared to $53,423 in the Greater New York area and $110, 292 in Manhattan.3 The three poor counties have continued to lose population over the last two decades. Here we have a first indication that place does indeed matter or, to be more precise, that location matters. Nebraska and South Dakota are neighboring states, located in the center of the North American continent. No two places have exactly the same location. All places in North America do not have the same potential for generating high incomes and job opportunities (maps 5 and 6). Nor do all places in Europe, India, China, and Britain have the same potential (maps 2, 9, 10, and 12). Explaining why this is so is the objective of this book.

The economic value of a particular place is perhaps best reflected in the price people are willing to pay to be there, which can be measured by land and housing prices. In the second quarter of 2008—the subprime crisis notwithstanding—the median price of a single family home in the New York area was twice that in the Chicago area and four times the price in Wichita, Kansas.4 Similar housing price differences exist between London and smaller British cities and between Paris and the rest of France or, for that matter, between any large metropolis and smaller cities. Only the most fortunate can afford an apartment in central London, Paris, Toronto, Hong Kong, Mumbai, etc. This brings us back to the question of the IT revolution. If, thanks to the Internet and all, it no longer matters where one resides, then why do people continue to pay a small fortune to live in downtown London, Paris, or New York? Why is Chicago “worth more” than Wichita? After all, information is as readily accessible in Wichita as in New York or Chicago, be it via the Internet, cell phone, TV, or Blackberry. Surely, we have missed something.

Why do people continue to flock to big cities? The great cities of China and India will soon reach populations unheard of in the history of mankind. Place obviously continues to matter to the millions of Chinese and Indians who, every year, make the move from rural places to urban places. Why do so many put such a high value on some places over others, high enough that they are willing to leave friends and family behind to move there? The answer, surely, is that some places generate greater economic opportunities than others. But why?

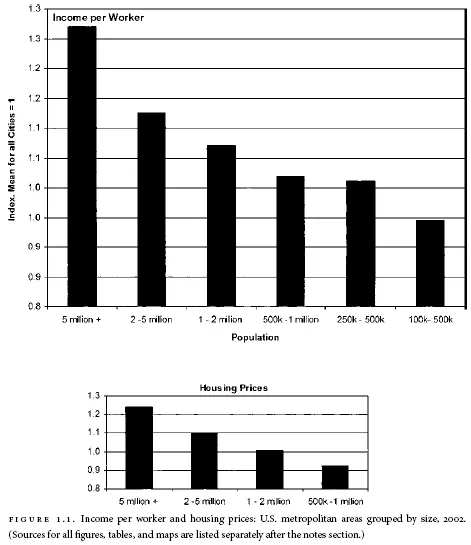

The previous paragraph provides a second clue. Size matters too. New York is bigger than Chicago and Chicago is bigger than Wichita, and all three cities are bigger than the rural communities of the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Kansas. The positive relationship between city size and higher incomes is one of the best documented in regional economics (figure 1.1). But why should size still matter in the age of the Internet? This question will continue to haunt us throughout this book.

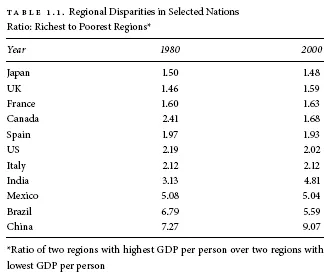

Wealth differences between places exist in every nation5 (Table 1.1). In the U.S., average product person in the two richest states is about twice that of the two poorest. In developing nations such as India and China, the gap between rich and poor regions is generally much greater. Herein is an additional clue. A link visibly exists between national economic development and the scale of wealth differences between places. We shall thus need to examine the relationship between national economic growth and the emergence of regional wealth differences. Why did such differences arise in the first place? Was there ever a time when they did not exist?

Table 1.1 contains another clue. National characteristics also matter.6 Why should the gap between rich and poor regions be greater in Italy than in Japan or greater in China than in India? Some possible answers are easy to imagine. One should, for example, expect the gap between rich and poor to be less in small nations where people can easily move back and forth between places. But surely the geography, history, and institutions of nations also matter. Here we find ourselves slowly gliding into evermore particular situations, which require knowledge not only of places, but also of the nations in which they find themselves. A small town in the north of England is not necessarily comparable to a small town in the Canadian Prairies, although both may be said to be peripheral in their respective nations.

The reality of place is multidimensional, not easily amenable to one-sentence descriptions. In all nations, the relative wealth (or poverty) of particular places is the outcome of the interplay between general forces—whose impact we are often able to predict—and unique stories. Which of the two carries the day in the end is the kind of question to which social scientists, myself included, are unable to provide simple answers applicable to every place, community, or region.

A PORTRAIT IN CONTRASTS

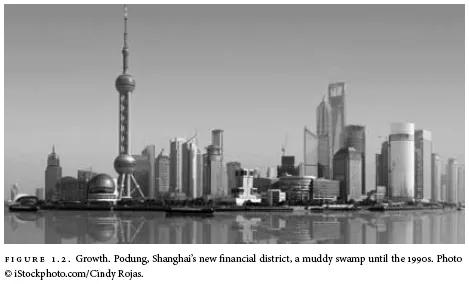

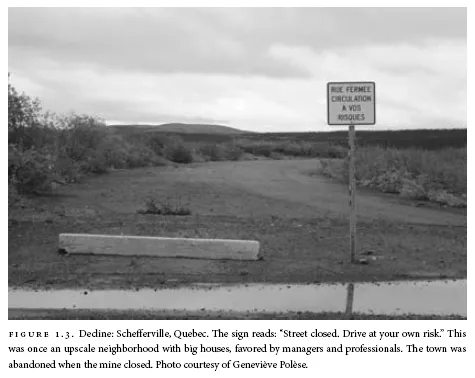

The two places pictured in figures 1.2 and 1.3 present a striking contrast in economic fortunes. Fist, we see Podung, the new financial district of Shanghai. There is a good chance that Shanghai will one day emerge—perhaps sooner than later—as a the leading global business center, challenging New York and London, and perhaps grow to become the world’s largest city. It is already China’s largest. It is easily the richest place in China, excluding the special case of Hong Kong. Clearly, Shanghai is favored by both size and location. Its position as a seaport at the head of the vast inland Yangtze waterway system is an obvious advantage, as is its central location on the Chinese seaboard between Hong Kong and Beijing. The size of the Chinese market is an additional factor, as is the direction of trade, a clue that the size and trade relationships of the nation in which a place finds itself will influence its fortunes. Nor can history and politics be excluded. Prior to the communist victory in 1949, Shanghai had developed a proud commercial and cosmopolitan tradition, which set it apart in China. In 1990, the choice by Chinese authorities to establish the first comprehensive free trade zone in Shanghai gave it a head start over other cities. Finally, had the Chinese government chosen not to open the national economy, Shanghai would most certainly have evolved differently. There would probably have been no Podung district of which to take a picture.

Schefferville, Quebec, by contrast, is not a happy story, a sad example of boom and bust. Technology and globalization can be said to be the chief culprits. The 2006 Canadian census puts its population at 202 inhabitants, down from 240 in 2001. In the 1970s, its population exceeded 4,000, a major iron mining center. The mine closed in 1980 because: 1) the demand for iron fell as other lighter materials and alloys (aluminum especially) replaced steel in many products; 2) cheaper iron ore deposits came on stream elsewhere (notably in Brazil) as shipment and transport costs fell. Schefferville ceased to be a competitive location once it became possible to bring in equally high-grade ore from Brazil at lower cost. Within Canada, Schefferville is favored neither by size nor location, situated far from major markets, which in the end precluded a move into other industries after the mine closed. The Schefferville story is an illustration of the double-edged sword that is natural resources: sources of wealth on the one hand, but also potential sources of poverty. There is no more fickle resource than a natural resource, a reality that we shall encounter again in this book.

The Schefferville story also tells us that falling transport costs can have both positive and negative consequences, depending on a place’s initial location. But wait, if falling transport costs can work both ways, cannot the same reasoning be applied to falling communications costs? Lower transport and communications costs heighten competition between places, bringing them closer. And, as with any competition, there are inevitably winners and losers. Who comes out on top is rarely a foregone conclusion. The relationship between falling communications costs and greater competition provides a first clue as to why the IT revolution might actually increase the importance of place. A shrinking world is not a placeless world. The “place” Schefferville did not cease to exist, but it did decline, a reality which no amount of Internet or IT could alter.

Competition between places, communities, and regions is not exactly the same as competition between nations. The fundamental difference is openness. Places, communities, and regions do not have real economic boundaries, although they can have political or administrative boundaries. Only in the European Union, which has almost totally eliminated the barriers to trade and travel between sovereign states, is the distinction blurred. In federal nations such as the U.S., Canada, India, and Australia, constituent states can have considerable economic powers; but they rarely hamper the free movement of people, goods, and money. It is entirely unimaginable that immigration controls should exist between, say, Illinois and Wisconsin or between Alberta and Saskatchewan. Between places, the flow of people, goods, and money is essentially free, held back only by geography, distance, and, in some cases, difference in culture and lifestyles. This is no minor distinction, for it means that a place, unlike a nation, can rapidly gain (or lose) resources, whether human or physical. The wealth of regions is more fragile than the wealth of nations. A region’s fortunes can go from good to bad—or the other way around—in the space of a generation, which is exactly what happened in the case of Schefferville, admittedly an extreme case. A place’s fortunes can change because technology has changed, because a new transport link was built, because of new consumer fads or because of any number of unpredictable events.

The world of regional economies is a porous one, with places continually exposed to plants opening and closing and people constantly moving in and out... and little that communities can do about it, at least not in most cases. Policy levers at the local level are generally limited, although this can vary depending on the size of place and the political structure of the nation. An American state or Canadian province has more power than a township, county, or city. However, this does not alter the fundamentally open nature of all their economies. Even in a highly regimented society such as China’s there is in the end little that local authorities can do to stop migrants from coming into the city.7 Places, by their very nature, are continually exposed to what happens elsewhere.

WHY THE GAP BETWEEN THE NORTH AND THE SOUTH OF ENGLAND?

Britain provides a particularly instructive case, highlighting several reasons why certain parts of a nation might systematically prosper—and draw in populations—compared to others. Urban size alone, which favors London, cannot explain the severity and persistence of regional income and product differences in Britain, specifically between Greater London and the surrounding southeast and the rest of the nation.8 We need to look at geography and the role of trade. Economic activity is naturally drawn towards places that offer the best access to markets. The EU is Britain’s dominant trading partner. When the nation’s largest city, London, is located in that part of the nation also best positioned for trade, the result is likely to be an economic divide that consistently favors one region: the south of England in this case.9

Historically, economic activity in Britain has largely evolved along a broad northwest-southeast axis stretching roughly from the Manchester-Liverpool duo and nearby Leeds and Sheffield down to Birmingham and, finally, Greater London (map 11). Before the Second World War, it would not have been a total exaggeration to assert that England (I shall concentrate on England, for simplicity’s sake) had a bipolar economic geography, with one pole looking west across the Irish Sea and the Atlantic and the other looking east across the North Sea and the Channel. With a little imagination, one could draw an analogy with the United States and declare that Greater Manchester (plus Liverpool) was England’s Los Angeles and that Greater London was England’s New York, with Birmingham in the middle cast in the role of Chicago. Notwithstanding London’s historically dominant role, the other poles were powerful contenders during the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century.10 Manchester, as any student of economic history knows, is the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, rising to become the most important industrial center in the world in the early nineteenth century. Manchester was the site of the first passenger railway between major cities, connecting it with Liverpool in 1830. Manchester in the nineteenth century was one of Europe’s leading intellectual and financial centers. Benjamin Disraeli is reputed to have said at the time that “Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athen...