![]()

Part I

History in Bones

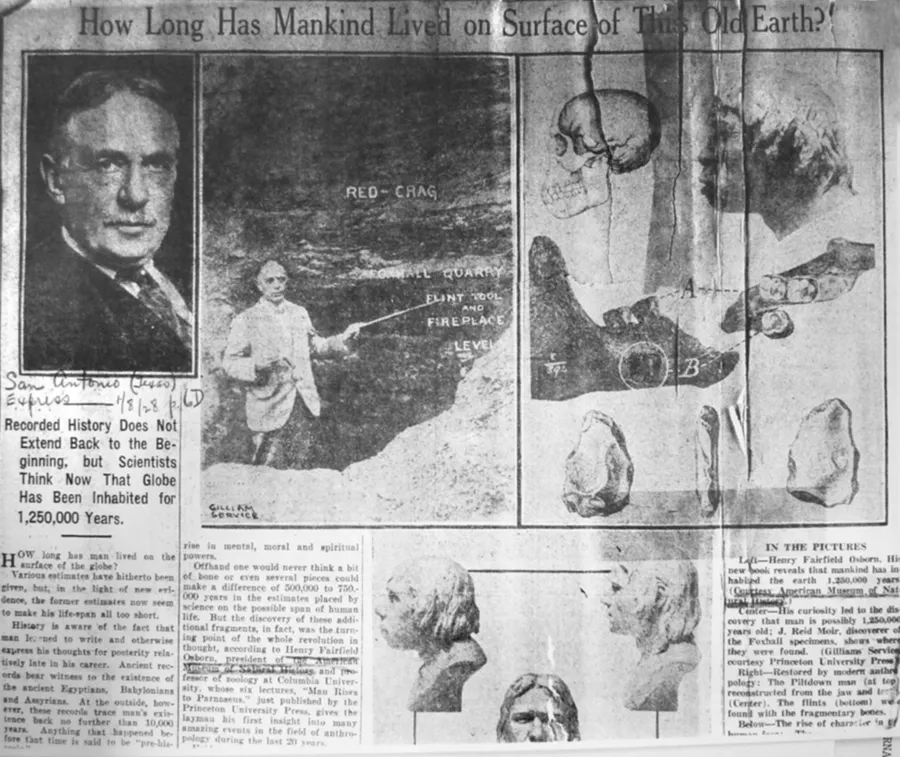

Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857–1935) at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) presents to the visitor the different branches of knowledge that throw light on the history of the universe, the earth, its life, and of humans and their cultures. Besides paleontological and geological exhibitions, there are astronomic, biological, and anthropological halls. The museum celebrates evolution. Its message is that “our” history is an evolutionary history and spans an immense amount of time, during a comparatively tiny part of which the earth had been populated by animals and humans that are now mostly lost. An excerpt of that evolutionary history—the history of the vertebrates—was already conveyed to a large New York, American, and international public in the decades around 1900 through the terrific Hall of Fossil Reptiles, Hall of the Age of Mammals, and Hall of the Age of Man that had been created under Henry Fairfield Osborn’s aegis and “finished” in 1905, 1895, and 1924 respectively. And already Osborn emphasized that comparative anatomy and paleontology were sciences concerned with “our history” (Osborn 1927a, 146). In what follows, I focus on how the AMNH under Osborn functioned as a meaning-making machine regarding “our” evolutionary past.

As Ronald Rainger (1991) has shown in his scientific biography, Osborn belonged to the New York City elite, a network that played its part in securing Osborn the double mission of establishing a department of vertebrate paleontology at the AMNH and building up a biology division at Columbia University in 1891. The museum curatorship and presidency from 1908 enabled Osborn to carve out a place for the traditional disciplines of comparative anatomy and paleontology in university education besides the new experimental biology, and he recruited university graduates to set up these branches of research at the museum. Through this staff, the museum’s department of vertebrate paleontology became an international hub in the exchange of experts, knowledge, and objects. The museum acquired an archive of earth history for the department through acquisition and exchange as well as the organization of expeditions. This made it possible for Osborn and a diverse team of experts to reconstruct the lost worlds in exhibitions for the new mass audiences. As figure 1 suggests, Osborn and his staff made the museum reach out beyond its walls also with regard to human evolutionary history.1

Figure 2 shows Osborn’s library, located on the fifth floor of one of the turrets of the museum building. It functioned as his study and serves as a starting point to introduce my main concerns. It is like a microcosm of the global genealogies that Osborn helped establish and into which he inscribed his person and work. On the desk were photographs of his two sons. The walls were covered with engravings and inscribed photographs of pioneer scientists, including the paleontologist Georges Cuvier, evolutionists Georges-Louis Buffon, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, and Thomas Henry Huxley, the great geologist Archibald Geikie, and the hero discoverers of the supposedly oldest human-made tools: James Reid Moir and Ray Lankester. There were photographs of explorers such as Robert Peary, Fridtjof Nansen, Theodore Roosevelt, and Richard Byrd; cases filled with books and unbound pamphlets; and most of the remaining floor space was taken up by long tables that held fossil bones and teeth.2

Osborn stated in an address that his people came from a pure English stock that could be traced back to Scandinavia. He explained that his maternal surname Sturges was derived from the Scandinavian Sturge, meaning “strong.” Osborn came from Asbiörn, Scandinavian for “divine bear”: “Considering my roving propensities, combined with much old-fashioned religious sentiment, I like to think of the fusion of characteristics implied in the three words ‘strong-divine-bear.’” On his mother’s side, Osborn claimed among his closer ancestors a colonial warrior, “Indian fighter,” and leader in political, military, and ecclesiastical affairs. His grandfather, Jonathan Sturges, rose to become a leading merchant of New York, a cofounder of the Illinois Central Railroad, and president of the Chamber of Commerce. Osborn presented his father, too, as a self-made man who engaged in the East Indian trade and became a railroad tycoon. With this heritage Osborn accounted for his roving propensity and strength. To explain his religious sentiment, he referred to his birthplace Fairfield (Connecticut), “with its stern convictions as to what is right and what is wrong, with its pioneer spirit of Christian education and civilization.”3

These family morals come close to what Donna Haraway ([1989] 1992, ch. 3) has called “teddy bear patriarchy” in her analysis of the AMNH’s African Hall. She views the exhibition that Carl Akeley developed under Osborn’s presidency as a crystallization of the postbellum bourgeois values. The expression resonates with Osborn’s self-designation as strong-divine-bear. However, it is meant as a pun on Theodore Roosevelt, after whom the toy animal was named. Roosevelt was chair of the museum board and the AMNH’s most powerful patron. He became president of the United States in 1901, and in 1912 founded the Progressive Party, which stood for many reforms in education, housing, and labor. It was an alternative to both the traditional conservative stance toward social and economic issues and to various more radical streams of socialism and anarchism. It was associated with a patronizing philanthropy, also manifest in the museum’s goals. Haraway in particular shows that the dioramas in the Akeley Hall expressed gender and race stereotypes. Finally, Roosevelt also embodied the cultural tropes of the new masculinity, the adventurous and strenuous life, and stood for the ideals of the outdoor and conservation movements (see, for example, Roosevelt [1905] 1991). As we will see, these moral concepts were conveyed by museum exhibitions as much as by Osborn’s description of his forebears. And as the progressive politics were accompanied by conservative aims, the idolatry of the frontiersman, the adventurer, and the explorer took place within industrial capitalism. Indeed, the Jesups, Dodges, Morgans, and Roosevelts of politics, finance, and transportation constituted the trustees of the AMNH.4

This paradox of striving for social progress and a nostalgia for “the old ways” has often been ascribed to the transformations wrought upon society and landscape through the surge in industry, the increase in population and immigration, urbanization, money-driven business values, and such “isms” as corporate capitalism, commercialism, utilitarianism, materialism, and scientism. These transformations triggered a backward and inward orientation, a turn to the “original ways of being” most strongly connected to the loss of what was perceived as typically American wilderness and wildlife. The closing of the frontier in particular became a rationale for anxieties about the loss of manliness and adventure, of Darwinian struggle and individuality, and by inference about the degeneration of the individual, “the race,” and the nation. These anxieties were at the heart of the cult of the primitive, of which the second decade of the twentieth century saw many expressions beyond the conservation efforts and the outdoor movement: the establishment of Boy Scouts and hunting clubs; the nature writing of Jack London, John Burroughs, and John Muir; as well as a more widespread aesthetics and religion of nature and neo-Romanticism. To preserve, restore, or re-create wilderness also meant to ensure the survival of the real American type, of chivalrous values, self-reliance, general fitness, and morality.5

Re-creation in the sense of the reconstruction of nature in urban settings and the regeneration of the modern citizen was also a goal of the museum (Mitman 1996). Rainger (1991) has elaborated on how Osborn’s religious background and social position influenced his work in science and education. Osborn largely shared the moral outlook of the powerful and rich New York elite. They wanted the museum to be an instrument of modernization as well as a stronghold against the decay of traditional values. Like the universities, libraries, parks, and zoos that were being established, the museum was to function as a space of civic education. The racism and Nordic supremacism that lay beneath Osborn’s genealogical self-identification as being of Scandinavian and pure English stock were the flip side of this progressive effort. In his intellectual biography of Osborn, Brian Regal (2002, ch. 5) engaged with the direct synergic relationship between Osborn’s scientific and popular work and his involvement in the eugenics and anti-immigration movements, which he shared with friend and museum trustee Madison Grant. Osborn considered it necessary to prevent excessive immigration of south European and Asian types; to help the “multiracial” children in New York to improve themselves according to their potential; and to preserve the natural order of “races,” classes, and sexes against the erosive forces of the blacks’ and women’s movements. “Preservation” was generally an important concept in Osborn’s great project. He advocated not only the conservation of nature and animal species, but also the preservation of, above all, the “Nordic race” (also Rainger 1991, ch. 5).

Osborn’s predecessor to the presidency, the banker Morris K. Jesup, had been involved in forest preservation from the 1880s onward (Adirondack Forest Preserve, 1885). Exhibits at the AMNH expressed concern for the preservation of American nature, animals, and “primitive peoples.” These efforts of the 1880s and 1890s were developed into a specific museum policy of conservation under Osborn. He conceived of his scientific work and that of his colleagues at the museum as a grand effort in establishing an archive of the present and past for future generations: “‘The reason why certain of our expeditions are being pressed so hard at the present time,’ he said, ‘. . . is that the natural beauty and life of the world are vanishing with a rapidity that is unbelievable, both among the native races of men and of mammals on land and sea. Unless we secure the records of these races now we shall never secure them. . . . To get these things while they are procurable, so that other generations may know what the world’s life has been, is a great labor and a great duty.’”6

Osborn thus also engaged in the Boone and Crockett Club, founded by Roosevelt in 1887 for animal study, protection, and hunting (another well-known paradox), as well as in the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, the American Bison Society, the Save the Redwoods League, the National Conservation Congress, the National Parks Association, the American Nature Association, and many more. That the effort of conservation for future generations encompassed cultural preservation is manifest in Osborn’s participation in organizations such as the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society and memorial associations and commissions. Regarding his family history, Osborn was a member of the Fairfield Historical Society and the New England Historical Genealogical Society. Both the preservation of American natural and cultural history, and of his stock were integral to the attempt to protect and restore “the race”: an attempt to which his engagement in the Immigration Restriction League, the Galton Society, the American Eugenics Society, and the Aryan Society provide direct testimony (Osborn 1930b, 139–143).

However, for Osborn, the history and genealogy that needed to be preserved and reconstructed reached much further back in time. He succeeded in institutionalizing American leadership in vertebrate paleontology, and as president of the museum, he made the evolutionary history of vertebrates the main focus of research and exhibition. In doing so, he stood on the shoulders of Joseph Leidy, Nathaniel Marsh, and Edward Drinker Cope, and he could profit from the role fossils had played in nation building. As Keith Thomson (2008) and others have shown, paleontology had long since been providing historical narratives and American icons. This was true not only for the deep histories and animals such as the mastodon that were reconstructed from fossil remains, but also for the history of American paleontology and its pioneers. The traces of the American deep past were national treasures; they were also bones of contention between men and institutions devoted to paleontology, a natural history that was strongly associated with the westward movement and the resulting territorial conflicts. In “epic efforts” and public feuds, Marsh and Cope spearheaded the discovery of many dinosaur species in the 1870s. When Osborn later organized museum expeditions to the American western states and territories, this triggered the “second dinosaur rush,” in which the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh and all the other major museums followed with collecting expeditions.7

Concomitantly, dinosaurs conquered popular culture. A mastodon mount had been America’s first reconstruction of a fossil vertebrate, and in the 1860s, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins mounted the skeleton of a Hadrosaurus. Such a Hadrosaurus mount was bought by the Princeton University Museum. Arnold Henry Guyot, one of Osborn’s teachers at Princeton, hired Hawkins to paint murals of America’s Late Cretaceous environments. No doubt, these early reconstructions influenced Osborn’s later work at the AMNH. Generally speaking, even though there existed a tradition of mounting fossil vertebrates at museums, and even though the well-known Henry A. Ward of Rochester, New York, sold finished specimens, “it was not until Henry Fairfield Osborn pioneered the display of mounted skeletons at the American Museum of Natural History in 1891 that the modern era of fossil display began” (Thomson 2008, 312). With the mountings of Diplodocus carnegiei at the Carnegie Museum and the Tyrannosaurus rex discovered by Barnum Brown for Osborn at the beginning of the twentieth century, America had its new popular icons.8

Osborn deplored the fact that when his teams embarked on the job of reconstructing Tyrannosaurus rex, hardly anyone knew what a dinosaur was. He sent out invitations to important people, summoning them to the museum for a dinosaur tea—a T. rex. The event was covered by the newspapers, which triggered interest in the dinosaurs at the museum. In the end, Osborn would pride himself on having turned dinosaur into a household word: “More than that, it means something to them, a linking up of the present with the past.”9 Osborn took great pains to ensure that the general public made this link between present and past, to render the strange creatures and scenes from history meaningful to people. Fossil vertebrates and especially dinosaurs could well serve to teach the lessons of nature to museum visitors. But “our” own deeper history was most instructive. When groundbreaking finds were made, Osborn therefore turned to paleoanthropology. With the remains of Pithecanthropus erectus (today Homo erectus) brought to Europe from Trinil (Java) in 1895 by Dutch physician Eugène Dubois (1858–1940), there was fossil hominid evidence from outside Europe and beyond the age of the Neanderthals. In France, the murals at Les Eyzies proved the claim that the Cro-Magnons had engaged in cave painting, and the great paleoanthropologist Marcellin Boule described the nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton of La Chapelle-aux-Saints. Soon afterward “Piltdown Man” (Eoanthropus dawsoni) was “discovered” in Sussex, England—a combination of an apelike jaw and a rather modern-looking braincase that was only decades later definitively exposed as a forgery. Beginning with a tour of the major sites in Franc...