![]()

Chapter One

The Rise of the Cycling City

“It is safe to say that few articles ever used by man have created so great a revolution in social condition as the bicycle.” This bold pronouncement came not from an editorialist, philosopher, or partisan promoter but rather from the United States government. The official census of 1900 contained an exclusive “special report” on bicycles, which enumerated the economic scale of bicycle manufacturing, summarized the technological history of the machine, and waxed philosophic about the vehicle’s effect on humanity. The broad scope of the report was well warranted. After all, there had to be some explanation for the seismic changes the census reported. In the early 1880s, a few thousand cyclists lived in the United States. By the end of the 1890s, millions did. According to the 1890 census—the first to acknowledge a “bicycle industry”—twenty-seven American firms produced bicycles. In 1900, 312 were in business. The newly robust cycling economy employed roughly 1,700 workers in 1890; by 1900 that number grew tenfold. By the turn of the twentieth century, American factories produced more than one million bicycles annually.1 These statistics merely confirmed what was obvious to almost anyone living in the 1890s: bicycles had invaded America’s cities. That world—the cycling city—emerged almost as quickly as it disappeared.

Even as millions of Americans bought bicycles that looked more and more like the bicycles we know today, a lack of consensus still existed about what the bicycle really was. The indeterminacy of the bicycle—whether it was a vehicle for transportation or a plaything for recreation—was a persistent theme. Manufacturers and admen marketed bicycles as everything and to everyone. They courted the wealthy and middle-class professionals; women and men; those who sought adventure, speed, fashion, or a faster way to get to work. Their success was unprecedented. While much of the demand derived from middle-class Americans, cycling in the 1890s appealed to a broad group of city dwellers who bought and rode bicycles with varying motivations. As they did, they helped construct not only the cycling city but also the meaning of the bicycle itself.

Although the bicycle era peaked near the close of the nineteenth century, earlier bicycle models enjoyed a devoted, albeit small, following. In fact, humans were captivated by the notion of man-powered propulsion for centuries. In the seventeenth century, a French physician designed a four-wheeled carriage powered by a combination of planks, ropes, pulleys, and a pair of servant’s legs.2 But not until the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did the first prototypes of the bicycle emerge across Europe. Inventors initially produced “horseless carriages” that mimicked the horse-driven variety in nearly every way except for the power source. In 1816, the German forester Baron von Drais, in search of a faster way to survey his territory, designed the laufsmaschine, or “running machine.” The device moved with force generated by the rider’s feet pushing directly against the ground. Made of wood and built with iron tires, the aptly dubbed “draisine” merited a brief spurt of popularity in Europe and the United States (fig. 1.1). By the mid-1860s, velocipedes, a more modern, pedal-powered, two-wheel vehicle, began attracting the attention of Parisian gentlemen before making their way across the Atlantic.

These machines quickly produced a mini-craze of their own in the United States. Rinks built for velocipedes dotted American cities, but the effect on urban environments was minimal. Throughout the 1870s, even as French and English riders continued to experiment with the latest bicycle incarnations, the clunky machines failed to attract a sizable following in American cities.3 That the velocipede craze came and went so quickly rendered any future success of the bicycle doubtful.

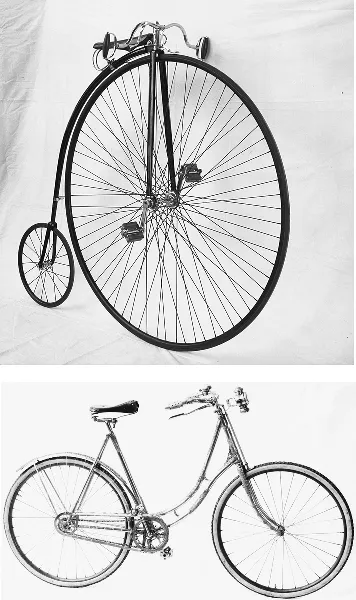

Wandering through the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, an unsuspecting thirty-three-year-old Civil War veteran was about to eye the machine that would forever change his life and the bicycle’s place in America. Albert Augustus Pope, honorifically referred to as Colonel Pope, joined nearly nine million fellow visitors in perusing the more than 250 pavilions that marked the nation’s one-hundred-year anniversary with displays designed to highlight technological and cultural progress. The telephone, typewriter, and a seventy-foot-tall Corliss steam engine were among the most talked about attractions. But it was the showcase of a high-wheel bicycle that infatuated the Colonel. Despite having no idea how to ride the “Pennyfarthing,” as it was dubbed in England, the Colonel was smitten. He soon set sail for England to inspect the manufacturer’s factory. After just a short stay, the Colonel was convinced. The cycling industry in Europe was quickening. In Great Britain alone, 50,000 cyclists rode through the streets.4 Pope foresaw that Americans would soon become bicycle crazy and that as a result, he would make millions of dollars. On both accounts, he was right.

The man who wore more of his salt and pepper hair on his face than atop his head did, in fact, become nineteenth-century America’s foremost bicycle tycoon. Although he had already had some success in manufacturing supplies and tools for shoemakers, the Bostonian dreamed of forging a bicycle empire. Like his few early competitors, he began by importing bicycles from England to test the market, but soon he built his own manufacturing facility in Hartford, Connecticut. Pope, who split his time between the factory and his Boston home, was certainly the most aggressive domestic producer, and he came to dominate the market. He began selling his latest high-wheel bicycles under the “Columbia” brand. Featuring an oversized front wheel (at least twice the size of the back wheel, although oftentimes much bigger) and a seat that rested about five feet above the ground, the high-wheeler was capable of achieving tremendous speed (fig. 1.2). Manufacturers quickly realized that since the pedals were attached directly to the front wheel, the larger the wheel, the farther a rider could travel with just one revolution.5

The high-wheeler posed a series of problems. Any dress-wearing woman daring enough to mount the saddle in the sky would have adopted a rather revealing pose. Few tried and even fewer became regular riders. Universally, the lack of stability and overall safety problems added significant danger. Because the seat typically rested above the disproportionately large front wheel, crashes often resulted in “headers.” Riders would fall forward, head first, to the ground. (There were no helmets.) The even bigger challenge involved mounting the bicycle. As Mark Twain, a high-wheeler disciple, explained:

You do it in this way: you hop along behind it on your right foot, resting the other on the mounting-peg, and grasping the tiller with your hands. At the word, you rise on the peg, stiffen your left leg, hang your other one around in the air in a general and indefinite way, lean your stomach against the rear of the saddle, and then fall off, maybe on one side, maybe on the other; but you fall off. You get up and do it again; and once more; and then several times.6

And that was coming from a man who had spent twelve hours in riding class.

Twain’s palatial, painted-brick, Victorian mansion sat just a half mile from the sprawling campus of Pope’s manufacturing center. The curious author had visited the factory, paid a handsome sum for one of the new machines, and enrolled in a cycling class. Like many others, he developed a love-hate relationship with his bicycle. (He once quipped “Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live.”) Despite Twain’s persistent instability atop the high-wheeler (a young onlooker once suggested that he “dress up in pillows”) he joined a thriving class of adventurous, affluent men who adopted the wheel.7 At a cost of $120 and oftentimes significantly more, the high-wheeler’s price limited its customer base and, since cycling was not yet “fashionable” in the way that it would ultimately become, these earliest cyclists represented but a small subset of the moneyed class.8 They tended to be young men of means, but not those who moved comfortably among the traditional elite. Mastering the high-wheeler took much skill and athleticism, virtues embraced by a sporting crowd. Still, there were enough people interested in cycling to attract a group of cunning businessmen. Together, they laid the groundwork for cycling to move into the mainstream.

The Safety Bicycle

By the close of the 1880s, the state of American cycling had come a long way since Colonel Pope first saw the high-wheeler in 1876. The packs of cyclists roaming through and between cities that once constituted only scores of riders now numbered in the thousands. The number of clubs devoted to the sport and magazines promoting it mushroomed. Nonetheless, after a decade or so of popularity, the high-wheeler began to disappear. Safety concerns, cost, and the lack of female ridership prevented any widespread adoption.9 Not surprisingly, manufacturers and would-be riders longed for a more appealing version.

By the late 1880s and the opening years of the 1890s, the “safety” bicycle began to replace the high-wheeler. The low-mounted version had a chain drive, two equal-sized wheels, and, ultimately, pneumatic tires (fig. 1.3). The inflatable tires represented a significant advance because they allowed for greater speeds, reduced vibrations, and, in due course, a detachable tire. Ball bearings, noticeably absent from some early models, helped reduce friction, and the new, easier-to-maneuver frame featured a lowered seat that attracted many who could never have mastered the art of (or those too frightened to have even attempted) mounting the high-wheeler. The new bicycles attracted an impressive following. In 1891 alone, Americans purchased around 150,000 machines, nearly doubling the existing sales.10 The rapid increase reflected a broader base of potential riders. After all, manufacturers derived the name “safety bicycle” in order to attract a different set of customers than the adventurous men who dominated the high-wheel market. The reduction in the average weight of a bicycle also made cycling more manageable for more people. Thanks to lighter frames, chains, and rims (wood as opposed to steel), the average weight of a bicycle dropped from about forty-two pounds in 1890 to about twenty-five pounds within a handful of years. Despite its name and the fact that it required much less athleticism and daring than what was required for the high-wheeler, safety bicycles were still popularly understood as vehicles for sport and recreation rather than utility. That the bicycle was elegant and speedy was more important than that it be durable.11

In contrast to other cyclists across the globe, Americans preferred their bicycles to be light and graceful above all else. To be sure, commuters, delivery boys, and other utilitarian users often emphasized the functional components of their wheels, but Americans generally stressed form over function. According to journalists at the time, the English preferred heavier, sturdier machines and the Chinese valued “strength, durability, and cheapness, rather than lightness and comfort.” The Japanese likewise selected their wheels for practical or business purposes, not leisure.12 Americans fancied wheels that might not have been ideal for transportation. American manufacturers, realizing the demand and helping to create it, marketed bicycles as the lightest on the market. Indeed, the particularities of bicycle design reflected more than just the ideas of an engineer; they also reflected customer input.13

Some cyclists even forwent brakes. Although a variety of brakes were available, many riders resorted to back-pedaling in order to slow their pace. Without brakes they saved a modest amount in weight and price. The trade-off for emphasizing light-weight was that those bicycles ideally suited for leisure were less practical as everyday vehicles and less likely to sustain the wear and tear of city riding. Serious buyers also carefully considered the size and quality of the single gear that powered most bicycles—a wise precaution, as the size would determine how difficult it was to push the pedals and the corresponding amount of power produced. Surely, many riders—especially those who found themselves occasionally climbing steep hills—regretted their choices. While the invention of the safety bicycle and its particular design was not inevitable, it did represent a breakthrough. Riders demanded stronger, lighter frames. The rough roads demanded better tires. Bicycle dealers demanded a shape that invited women and men of all sizes into their stores. And nearly all constituents demanded that bicycles be safer. The end result was a bicycle that is almost identical to the one we would recognize today.14

At the time, bicycles fascinated Americans as a modern piece of technology that could, in theory at least, usher in revolutionary changes to the urban world and stand as a sign that the modern age had come into being. So did its manufacturers. Nearly every year, bicycle models sported mechanical improvements and frills absent from earlier models. In fact, manufacturers in the 1890s sought patents to improve their bicycles at such an alarming rate that the US government created a special division within the Patent Office just to deal with bicycle-related patenting. Most of these innovations were minor, simply an excuse to issue another model and render the older versions out of date. In that sense, bicycles were one of the first luxury items in whic...