![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Rum Punch or Issue Voting?

In his long career as a public figure, James Madison lost only one election—his 1777 bid for a seat in the new Virginia House of Delegates. At the time, candidates for public office were expected to ply voters with liquor on Election Day; the favorite drink was rum punch. George Washington had supplied 160 gallons of alcohol to 391 voters for his successful 1758 election bid in Frederick County, Virginia (Labunski 2006). Madison, however, found this campaign tactic repulsive, “inconsistent with the purity of moral and Republican principles” (Labunski 2006, 32). Determined to introduce a “chaster” model of conducting elections, he refused to provide alcohol to voters in the 1777 election. His opponent, lacking such scruples, beat him.

Such apparently superficial judgments on the part of voters have always been one of the chief concerns with democracy. And even though most consider the worldwide spread of democracy since Madison’s day a stupendous achievement, concerns about voters’ judgments persist. Do voters still judge politicians on such irrelevant or superficial characteristics or do they vote on substantive matters?

In one view of democracy, elections are about substance; they are fundamentally about voters expressing their preferences on public policy (Dahl 1956; Pennock 1979). Voters judge, compare, and vote on candidates’ policy platforms. (Political scientists call this issue voting.) The voter thinks: “This politician supports the policies I think are right and so I will vote for him or her.” If this view is correct, politicians may generally reflect the will of the public. Citizens lead, politicians follow.

Other scholars consider the policy voting view unachievable. They see elections as periodic referenda on the incumbents or as a way of selecting candidates with the best character traits (Riker 1982; Schumpeter 1942). In this version of democracy, voters may focus on what I call performance-related characteristics, such as previous success in office and trustworthiness. The voter thinks: “This politician has the personal traits I think a politician should have. This politician has done a good job in previous political positions.” In this view, citizens don’t directly lead politicians on policy, but they do lead on performance, throwing out incompetent or corrupt incumbents.

We can also imagine a worst-case view of democracy, in which voters lack well-developed preferences about public policy and about politicians’ performance and, instead, blindly follow the views of their preferred party or politicians. They judge, compare, and vote for candidates according to other matters—anything from rum punch and good looks to overblown gaffes and an ill-fitting tank helmet. In this view, politicians make policy with surprisingly little constraint. They must still win elections, but they win or lose on what Alexander Hamilton called the “little arts of popularity.”1 Voters, having decided they like a particular politician for reasons having little or nothing to do with policy, may simply adopt that politician’s policy views. In this view, democracy is a farce. Politicians lead, citizens follow.

The main question I set out to answer is, which view of democracy best reflects modern reality? Do citizens lead politicians on policy? Do they judge them on performance-related characteristics? Or do they merely follow politicians?

To answer this question I administer a series of tests—some easy and some difficult—to assess citizens’ judgments of politicians. To do so I analyze how citizens respond to major and minor political upheavals induced by wars, disasters, economic booms and busts, and the ups and downs of political campaigns. I focus on citizens’ judgments of politicians who are holding or seeking the highest offices—president and prime minister—since if voters are going to pay attention to any political figures, it will likely be these.

I begin with what I argue is an easy test: do voters take into account factors that are relevant to a politician’s future performance, such as his or her past performance (on say the economy) or character traits that are relevant to future performance (such as honesty or competence)? I then move on to harder tests, focusing especially on whether voters take into account a politician’s policy views. Do voters decide which policies are best and then vote for politicians who support those policies?

The results paint a mixed picture of democracy. Voters do pass the relatively easy tests of judging politicians on performance. When people think a politician has performed well—perhaps by boosting economic growth or winning a war—they become or remain supportive of that politician. Likewise, when people perceive a politician as having desirable character traits relevant to performance, such as honesty, they become or remain likely to vote for that politician.

But voters fail the policy tests. In particular, I find surprisingly little evidence that voters judge politicians on their policy stances. They rarely shift their votes to politicians who agree with them—even when a policy issue has just become highly prominent, even when politicians take clear and distinct stances on the issue, and even when voters know these stances. Instead, I usually find the reverse: voters first decide they like a politician for other reasons, then adopt his or her policy views.

My results confirm the views of scholars who see democracy primarily as a means for voters to pass judgment on how well incumbent politicians have been performing rather than as a means for voters to express their own policy preferences. Although perhaps not everyone’s ideal, democracy should therefore at a minimum select competent leaders over incompetent ones. Voters may even be exercising an indirect influence on politicians’ policies by voting out leaders whose policies, in the voters’ eyes, have not turned out well.

My results are likely to disappoint scholars who see democracy as a means for voters to express their policy preferences. In fact, my findings suggest that this idea of democracy has been inverted. Voters don’t choose between politicians based on policy stances; rather, voters appear to adopt the policies that their favorite politicians prefer. Moreover, voters seem to follow rather blindly, adopting a particular politician’s specific policies even when they know little or nothing of that politician’s overall ideology. Politicians, these findings imply, have considerable freedom in the policies they enact without fear of electoral repercussions.

1.1 The Problem: Observational Equivalence

After decades of research into electoral politics, how can such important behavior on the part of voters still be in question? Determining whether citizens lead their politicians or follow them turns out to be a lot harder than it sounds. In fact, to the student of democracy, the policy-voting view and worst-case view can look identical. To understand how that can be so, consider an example from a US presidential election in which it appears, at least at first, that citizens led their politicians on policy.

FIGURE 1.1. Excerpt from address by President Harry S. Truman. Charleston, West Virginia, October 1, 1948.

President Harry S. Truman’s victory in 1948 was one of the great election upsets in American history. Long before the campaign started, journalists, pollsters, and pundits saw Truman’s defeat as a foregone conclusion.2 Nonetheless, Truman campaigned vigorously. He traveled the country by train to deliver his stump speech, excerpted in figure 1.1, in which he appealed to voters on public policy grounds. The Democratic Party, Truman told voters, had built prosperity for business, labor, and agriculture by enacting legislation that helped ordinary working men and women. Voters should vote for the Democratic Party because it supported the minimum wage, Social Security, and the right to organize unions and bargain collectively. “We put a floor under wages,” Truman declared. “We outlawed child labor.” On Election Day, Truman defeated Thomas E. Dewey, the Republican candidate, by a respectable margin, with 49.6 percent of the vote to 45.1 percent (303 electoral votes to 189).

If the policy-voting view does accurately depict democracy—that the public leads on policy—then Truman’s victory is likely attributable to the public’s reasoned judgment of his policy stances. He won because his campaign brought his policies to the attention of voters, allowing them to choose based on their own policy views.

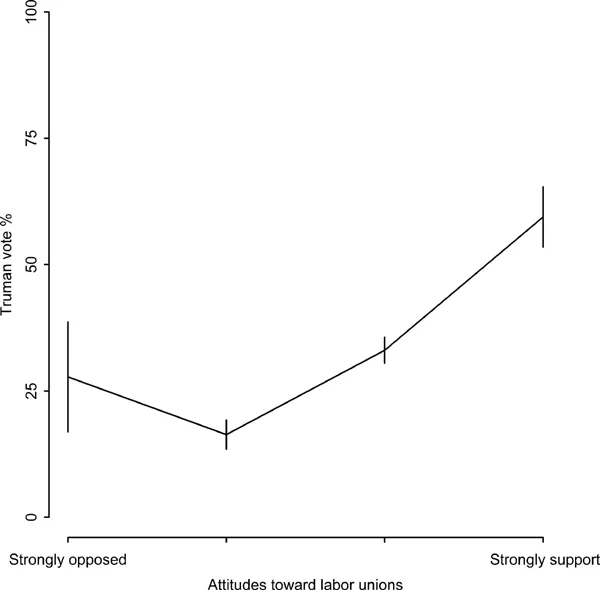

In a classic study of Truman’s come-from-behind victory, Paul Lazarsfeld and his colleagues reach precisely this conclusion: “An impending defeat for the Democratic Party was staved off by refocusing attention on the socioeconomic concerns which had originally played such a large role in building that party’s majority in the 1930s” (Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954, 270). Are Lazarsfeld and his colleagues right? The evidence supporting their view primarily concerns one issue on which the candidates had clear and distinct positions: government policy toward labor unions. Before the election, the Republican-led Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, considerably restricting labor union organizing. Truman opposed the legislation, while Dewey supported it. If this issue did sway voters, we should find that union supporters tended to vote for Truman while opponents tended to vote for Dewey. And indeed, Lazarsfeld and his colleagues conducted a preelection survey in October 1948 that found that among those who said unions “are doing a fine job,” about 60 percent intended to vote for Truman, but that among those who said the country would be “better off without any labor unions at all,” less than 30 percent intended to do so.3 Figure 1.2 shows this relationship, apparently confirming that voters—at least on this issue—did lead politicians, voting for the one who shared their policy views.

Unfortunately for democracy, there is also a less flattering interpretation of Lazarsfeld’s survey results. Imagine a world in which voters in the 1948 election utterly lacked views about unions. Many voters, however, liked Truman for other reasons, especially the nation’s robust economic growth, and intended to vote for him on those grounds.4 In such a world, voters who had already intended to vote for him may have adopted his prounion policy view.5 Likewise, voters who had already intended to vote for Dewey may have adopted his antiunion policy view. In such a world, Lazarsfeld’s survey would have produced the same results and the election would have gone the same way. We are left with a dilemma. From the evidence presented so far—both Lazarsfeld’s survey and the actual election—we cannot tell which came first, the voters’ attitudes about unions or their choice of candidate, a problem researchers call reverse causation.

FIGURE 1.2. Leading or following on policy? Support for unions is positively associated with support for Truman (among those voting for Truman or Dewey) in the October interviews of a 1948 study—a pattern that could result either because union supporters voted for Truman because he shared their views (leading) or because Truman voters adopted his views on this issue (following). Error bars give 68 percent confidence intervals (one standard error). I show 68 percent confidence intervals whenever readers will want to compare means (checking whether these error bars touch provides a conservative differences-in-means test). Source: 1948 Elmira study (Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954).

More generally, we cannot tell from such data—the correlation of policy views and vote choice—whether we are observing the policy-voting view of democracy, in which the people lead their politicians on policy, or a worst-case view, in which the people follow their politicians on policy. Like a bright star that is far away and a dim star that is near, these two conditions are very different, but we can’t tell them apart without additional information. They are observationally equivalent.

1.2 The Literature: Lack of Consensus

Researchers don’t give up easily. They have tried to overcome the observational equivalence problem with such social science tools as randomized experiments and structural equation modeling. These methods, however, have failed to settle the debate.6 The result is that scholars have been unable to reach a consensus about whether citizens lead or follow, and several opposing schools of thought continue to flourish.

On one hand, some researchers believe democracy resembles the policy-voting ideal. According to this view, voters lead their politicians by selecting them on policy grounds, just as Lazarsfeld and his colleagues contend that voters chose Truman over Dewey because a majority agreed with Truman’s policy views and disagreed with Dewey’s.7 (Although we know that voters are often surprisingly ignorant about politicians’ policy views, they may rely on reasonable substitutes for direct knowledge—which researchers call heuristics—such as party identification [Popkin 1991]. That is, I may not know a particular Republican candidate’s position on offshore drilling, but I know the Republican Party’s position and I agree with that.) Since this line of scholars sees policy and performance judgments as the basis of a voter’s choice, they would describe the reality of democracies as being close to the policy-voting view.

But another line of scholarship paints a much darker view. They see voters as being influenced by superficial or random factors, ranging from candidates’ faces (Todorov et al. 2005) to the happenstance of natural disasters (Achen and Bartels 2004a) to the fortunes of a local sports team (Healy, Malhotra, and Mo 2010). This research could describe the reality of democracies as being closer to the worst-case view.

Of course, most schools of thought place democracies somewhere between the policy-voting view and worst-case view. A prominent school, exemplified by Angus Campbell and colleagues’ The American Voter (1960), views party identification as the core of voters’ political behavior. According to this view, people identify with political parties early in life and rarely, if ever, change. This identification typically develops from socialization through one’s parents, though policy views and party performance may also play a role. Once identified with a party, voters pick that party’s candidates and adopt that party’s policy positions.8 In this scenario, citizens primarily follow rather than lead their politicians, and democracy succeeds to the extent that the party elites act wisely.

Another group of scholars contends that voters vote primarily on performance rather than policy. Morris Fiorina (1981) exemplifies this view, claiming that many voters find direct judgments on public policy too complicated but are quite able to judge a politician’s performance in office. For example, voters may be overwhelmed by the complexity of a health care policy debate, yet feel that they know whether or not the policy in place is working. In this view, citizens do lead, but only after the fact, throwing out incumbents who pursue failed policies.

Each of these views has been supported with evidence. The result is that we still do not know which view of democracy is correct.9

1.3 A Solution to Observational Equivalence

The cause must be prior to the effect. (Hume 1888, 173)

To overcome observational equivalence—to sort out cause from effect—this book brings together data with two crucial qualities. First, it uses surveys that reinterview the same person multiple times, which researchers call panel surveys. These help us sort out what is causing what because we can measure people’s views before they experience the campaign or other political event that we think might have affected those views. We can then test whether they later bring their support for politicians in line with their earlier stated views; that is, whether they lead. We can also test for the reverse process: whether voters bend their performance assessments or policy views to match their party identification or candidate preferences; that is, whether they follow.

On its own, however, measuring the cause before the effect—measuring policy or performance views before measuring changes in vote or candidate ev...