![]()

A Nation among Nations: Shimon Benizri

![]()

![]()

Lo yisa goy el goy echad.

No nation is a nation alone.

—Hebrew song

Sefrou, Morocco, June 5, 1967

The radio had gone silent. For several days I had been switching back and forth among Moroccan and European broadcasts, following the growing tensions between Israel and the surrounding Arab states. But when the Moroccan national broadcast was abruptly interrupted, I knew events must have taken a turn for the worse. A few moments later the station resumed—but now with martial music and exhortations from the government, politicians, and doctors of Islamic law. In the absence of solid news I tried to convince myself that perhaps it did not really signal the start of hostilities. That hope, however, was short lived. As I raced back and forth across the dial, I soon heard the Moroccan station announce that what was later to be known as the Six-Day War had indeed commenced.

Initial reports on the Moroccan stations were contradictory. One said that Tel Aviv had been bombed; another played classical music interspersed with announcements that could only suggest Israeli advances. The radio also indicated that Moroccan troops would be sent to combat Israel, and it was said that America was assisting the Jewish state. My own situation, however, was not deeply affected. A few days later the chief judge of the district in whose court I had all but completed a study—a man whom I would later get to know well and for whom I have the deepest respect and affection—said that it was too much trouble for the clerks to be getting records out for me and that I should not return to the court for the time being. Even Haj Hamed suggested we keep our heads down and not do too much traveling for the moment. During my seventeen months of fieldwork I had not once encountered any difficulties, and though I had not focused my research on the significant Jewish community still residing in Sefrou, the tenor of communal relations had never been a cause for concern. Nor did I feel any anxiety as a result of my own living circumstances.

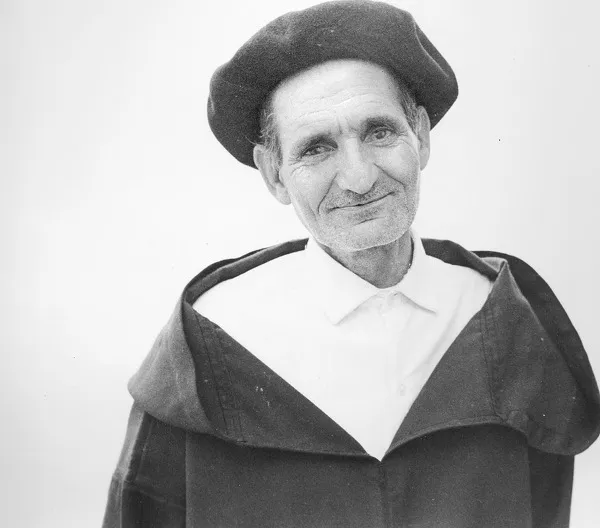

At the time the war began, I was residing just outside the old city walls in one of four apartments that shared a small courtyard above the shop of Malka, a Jewish furniture maker. One of the apartments was occupied by a young Muslim couple—she an Arab from the city, he a Berber from the nearby Middle Atlas Mountains. The other two apartments were occupied by Jewish families. To one side lived a couple, the Poneys, she a thin fidgety woman always nervously tweaking a headscarf of the type married women of the Jewish community commonly wore, her husband a sickly-looking man invariably dressed in a gray djellaba and black beret, the latter having once been the sign of a French protégé or, for others, something of a protest against the pre-Protectorate garb expected of Jews.

But it was the other family I came to know best. For just across the tiled common space lived Shimon and Zohara Benizri and seven of their eight children—he a quiet man in his late fifties, a warm smile permanently affixed on his boyish face, she a short, bustling, ever-optimistic woman efficiently managing a household of rambunctious children. In those first few moments my thoughts turned to all of the city’s Jews and to what this war might mean to their continued willingness, unlike most of their coreligionists in Sefrou and Morocco as a whole, to remain in the country. But it was not until I went out to talk with others that I could begin to see, in this moment of potential crisis, just how entangled were their lives with those of their Muslim neighbors.

A group of Muslims gathered around the post office spoke animatedly about how the Jews were now going to get their comeuppance while others used phrases—“May Allah bring good things,” “It is all in Allah’s hands”—that by their very indirection often signal that matters are not always as obvious or predictable as they seem. Elsewhere I saw Jews and Muslims speaking quietly to one another. I talked with a number of the Jews, who seemed mostly confused and helpless rather than threatened, but who nevertheless went about their business normally. Later, one of the Benizri children told me that Muslim kids had gathered around their school and were throwing stones until the police were called and dispersed them. I even learned that one Jewish man had gone to donate blood for the Moroccan troops who were to head for the front. But the Muslims who later told me the story laughed and said that while it was a nice gesture, they would, of course, have to throw out his blood, because everyone knows that Jewish blood doesn’t work on Muslims. The most striking moment, however, came that first evening when a visitor arrived at the Benizri residence.

The visitor—who also brought his wife and teenage boy with him—was the son of a man named Caid Said, who had formerly given his protection to Shimon, and before him to Shimon’s father, when they lived and traded in the mountains. He was an elegant man, dressed in a flowing djellaba and carefully wrapped turban, his sun-ripened face framed by a blazingly white beard. He was also a wealthy man who had twice gone on the pilgrimage to Mecca and who was the undisputed leader of his tribal fraction located in that part of the Middle Atlas Mountains where Mrs. Benizri had grown up. As soon as the war broke out, he had begun the long trip to the city with his young wife for the express purpose of assuring the Benizris that no matter what happened in the Middle East, they had no reason to fear for their personal safety or that of their property. He spoke calmly and reassuringly of the fact that they were all Moroccans and that the government would protect them. He offered his personal help, specifically suggesting that during the next few weeks they jointly rent a house in the old Jewish quarter where the Benizris could live upstairs and he and his family downstairs, between them and the outside world, a partnership arrangement that was actually not uncommon at many times and places in Morocco.

Shimon graciously refused the offer, saying they felt quite safe where they were (especially with their American neighbor so close by). The visitor then suggested that they at least allow him to leave his own son to sleep outside the staircase leading up to our apartments as a sign that any attack on this family would be an attack on him as well. Again, Shimon and Zohara demurred, pointing out that the house could easily be locked and that it was only children who were causing any disturbances. Upon learning of the children’s stone-throwing, Caid Said’s son reminded Shimon that the Berbers could offer better protection than the government should the Benizris at any time change their mind and decide it would be best to leave the city for a while. They parted late that night with the Berber assuring the family that he and some of his boys would be keeping a watchful eye on Shimon’s stall in the marketplace in any case.

Throughout the six days that the war lasted, life in the city remained virtually unchanged on the surface. Those people who felt most strongly about the war expressed the greatest opposition to Israel’s continued existence, and those who were most certain of a quick Arab victory came mainly from the segment of educated urban Arabs. The poorer people of the city and the Berbers of the countryside talked about making a peaceful settlement and the difficulty of keeping straight who was who in the war. (Does Iraq have a common border with Israel? Where exactly is Syria?) And they stressed that the whole business should certainly not affect the Jews of their own city.

Beneath the surface, however, among Muslims and Jews alike, the dominant feeling at this point was one of uncertainty. As one Jewish man told me, “Everything would be all right if people today respected the old ways and continued to treat us as individuals. But nowadays there are so many unemployed people in town who could be turned against us at any moment.” A Muslim shopkeeper spoke in similar terms: “You have to understand the custom in this country,” he said. “People do whatever some big man tells them to do. What they are told to do doesn’t matter nearly as much as the fact that someone takes hold of things and tells people how they should act. If the government does nothing and someone tells people to kill the Jews, that is what they may do. If the government tells us to be good to the Jews, we will follow their directions.” An attempt to provide some such authoritative direction was not long in coming.

On June 12 the newspaper of Istiqlal, the main conservative political party in Morocco at that time, called for a boycott of “all those who have close and distant ties with ‘Israel’ and her sinister allies.” They also published a list of companies that, they said, dealt with Israel and should be boycotted. The more conservative Arabs of the city now had their direction: they said they would have no business dealings with Jews, since all Muslims must unite in the face of the outside enemy. Jews remained off the streets, some even afraid to try buying food. Unarmed soldiers—including one stationed, symbolically, at the gate of the old Jewish quarter in the center of the city, a place where no Jews any longer resided—joined the local police in casually patrolling the city as the government began to clarify its own position. On June 14, the Moroccan representative to the United Nations spoke at length of the favorable treatment Jews had always received in Morocco, particularly when the late king, Muhammad V, resisted the anti-Jewish legislation of the Vichy regime during the Second World War. A similar statement from the Royal Cabinet released two days later further emphasized that none of the citizenship rights of Moroccan Jews would be altered in any way by the current situation. Meanwhile, on June 15 the government seized the Istiqlal party newspapers; when the papers reappeared two days later, the call for a boycott was only slightly toned down, although no specific nations or companies were mentioned by name.

The Jews of the city, meanwhile, played for time. With the boycott in partial effect and some of the Muslims actually intimidated into not patronizing Jewish-owned shops, individual Jews reasoned that they could close their businesses on Wednesday and Thursday (June 14–15) for the Jewish holiday of Shevuoth, open briefly on Friday (the Muslim “Sabbath”), stay at home over the weekend, and go back to work on Monday—the day before the Muslim holiday celebrating the Prophet’s birthday. The Jews felt that in the interim many even normally unemployed Muslims would become busy harvesting the area’s first grain crop in two years. Moreover, unless the fighting in the Middle East resumed and the local Muslims were forced to remain united against an enemy whose presence they could be made to feel personally, internal Muslim differences would reassert themselves, and the Jews would once again be able to work within the context of their personal and social relationships with the Muslims. Realizing, however, their complete political impotence, the Jews feared that in the days following the war they might find themselves used as pawns in the struggle among the various Moroccan political factions.

For the most part this fear proved groundless. Intent on preserving public order and not allowing the politicians to seize the initiative, King Hassan II took a strong stand in favor of protecting all Moroccan citizens—Jews and Muslims alike—from violent action. As the United Nations debated on into deadlock, Istiqlal continued to call for a boycott of Jews and the nationalization of some Western-owned firms. Dubbing the boycott an act against the order of the state, the government struck back on July 5, charging that “the boycott is not an Islamic principle. . . . Those who incite people to participate in it commit an act that is criminal in thought, in law, and in spirit.” Then on July 8, in a most remarkable televised speech, the king himself argued that it was not surprising that the world should regard the Arabs as the aggressors in the recent war, since it was they who called for a general mobilization a week before the fighting began and it was they who closed the Gulf of Aqaba. He said that one should never enter into a war until one’s own country is at least the economic equal of the opponent, and he stressed the point that internal chaos is far worse than an undesirable international political situation. The king’s verbal determination was expressed in action a few days later when the head of the largest labor union in the country was imprisoned for charging that the Moroccan government itself had fallen into the hands of pro-Zionist forces. The papers of the Istiqlal party, threatened with another seizure, turned to a direct attack on those whom they regarded the king as coddling, and they initiated a series of articles on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the notorious forgery about the Jewish world conspiracy of which the Nazis had made such effective use. Yet even here it was clear that the Moroccans, like President Nasser of Egypt, had to borrow their anti-Jewish text from another cultural tradition simply because the Arabs lacked a well-developed anti-Semitic literature of their own.

Significantly, however, within the city itself the impact of this struggle for power and influence on the national level was minimal. The king’s strong stand concerning any sort of illegal action against the Jews was not without its effect, but the local situation had already begun to ease well before Hassan’s position was fully clarified. Most Jews reopened their shops right after the holiday of the Prophet’s birthday, and Muslims and Jews joked and conversed in near normal fashion. With the passage of time and the continued bickering among the various political factions, the people of the city reasserted their suspicions about all national party leaders and their abiding faith in personal judgments based on face-to-face relations. Those Jews who practiced trades or sold goods without competition from Muslims were fully patronized. Some urban Arabs and fewer Berbers, perhaps hedging against any later claim that they had supported Israel’s friends, avoided Jewish shops that were in direct competition with Muslims while still remaining cordial in their relationships with individual Jewish businessmen. Rural people practiced this avoidance even less on market days, when there were enough of them in town so they could not easily be intimidated by some of their more partisan urban brethren.

Witnessing the events surrounding the war, I often found myself intensely curious about the relations between the Muslims and Jews but not especially surprised. Much of what happened—from the extraordinary visit of the son of the Benizris’ Berber protector to the king’s speech—fit with what I had come to understand about Moroccan communal history. That it was by no means an unambiguous history was made all the more apparent when, sometime later, I began to place Shimon’s own life story within the broader context of Moroccan social history.

•

There was, until there was, in times so fair,

When basil and lilies grew here and there,

And God was to be found everywhere.

—Traditional story opening

I was born in 1910, Shimon began, up in the Middle Atlas Mountains, at a place called Almis d-Marmousha. My father and all those before him came from Midelt, a high-...