eBook - ePub

Quantifying Systemic Risk

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Quantifying Systemic Risk

About this book

In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis, the federal government has pursued significant regulatory reforms, including proposals to measure and monitor systemic risk. However, there is much debate about how this might be accomplished quantitatively and objectively—or whether this is even possible. A key issue is determining the appropriate trade-offs between risk and reward from a policy and social welfare perspective given the potential negative impact of crises.

One of the first books to address the challenges of measuring statistical risk from a system-wide persepective, Quantifying Systemic Risk looks at the means of measuring systemic risk and explores alternative approaches. Among the topics discussed are the challenges of tying regulations to specific quantitative measures, the effects of learning and adaptation on the evolution of the market, and the distinction between the shocks that start a crisis and the mechanisms that enable it to grow.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Liquidity Risk, Cash Flow Constraints, and Systemic Feedbacks

1.1 Introduction

The global financial crisis has served to reiterate the central role of liquidity risk in banking. Such a role has been understood at least since Bagehot (1873). This chapter develops a framework that promotes an understanding of the triggers and system dynamics of liquidity risk during periods of financial instability and illustrates these effects in a quantitative model of systemic risk.

The starting point of our analysis is the observation that although the failure of a financial institution may reflect solvency concerns, it often manifests itself through a crystallization of funding liquidity risk. In a world with perfect information and capital markets, banks would only fail if their underlying fundamentals rendered them insolvent. In such a world, provided valuations are appropriate (e.g., adjusted to reflect prospective losses), then examining the stock asset and liability positions would determine banks’ health, and solvent banks would always be able to finance random liquidity demands by borrowing, for example, from other financial institutions. In reality, informational fr ictions and imperfections in capital markets mean that banks may find it difficult to obtain funding if there are concerns about their solvency, regardless of whether or not those concerns are substantiated. In such funding crises, the stock solvency constraint no longer fully determines survival; what matters is whether banks have sufficient cash inflows, including income from asset sales and new borrowing, to cover all cash outflows. In other words, the cash flow constraint becomes critical.

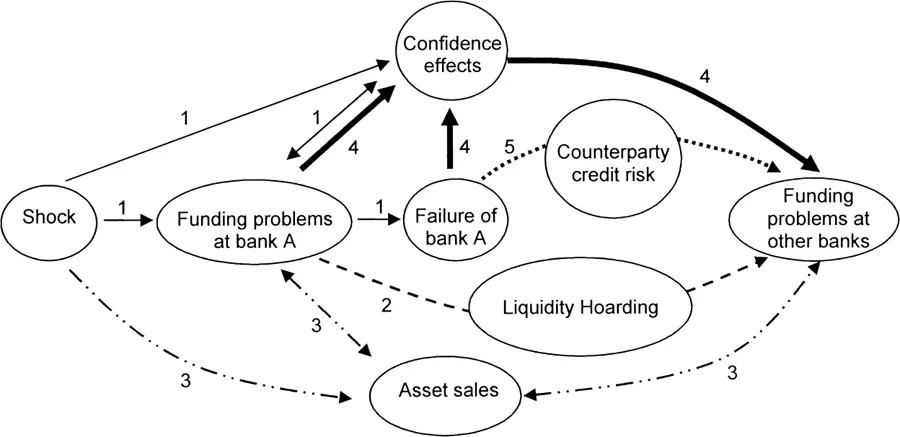

Fig. 1.1 Funding crises in a system-wide context

The lens of the cash flow constraint also makes it possible to assess how banks’ defensive actions during a funding liquidity crisis may affect the rest of the financial system. Figure 1.1 provides a stylized overview of the transmission mechanisms. For simplicity, it is assumed that the crisis starts with a negative shock leading to funding problems at one bank (bank A). The nature of the shock can be manifold—for example, it could be a negative earnings shock leading to a deterioration of the bank’s solvency position or a reputational shock. After funding problems emerge, confidence in bank A may deteriorate further, either endogenously or linked to concerns about the shock (channel 1 in figure 1.1).

In an attempt to stave off a liquidity crisis, the distressed bank may take defensive actions, with possible systemic effects (channels 2 and 3). For instance, it may hoard liquidity. Initially, it may be likely to start hoarding (future) liquidity by shortening the maturities of the interbank market loans it provides. This is advantageous to bank A as shorter-term loans can be realized more quickly and hence may be used as a buffer to potential liquidity shocks. More extremely, the distressed bank could also cut the provision of interbank loans completely, raising liquidity directly. Both these actions could create or intensify funding problems at other banks that were relying on the distressed bank for funding (channel 2). The distressed bank could also sell assets, which could depress market prices, potentially causing distress at other banks because of mark-to-market losses or margin calls (channel 3). In addition, funding problems could also spread via confidence contagion, whereby market participants decide to run on banks just because they look similar to bank A (channel 4) and, in the event of bank failure, through interbank market contagion via counterparty credit risk (channel 5).

The main innovation of this chapter is to provide a quantitative framework showing how shocks to fundamentals may interact with funding liquidity risk and potentially generate contagion that can spread across the financial system. In principle, one might wish to construct a formal forecasting framework for predicting funding crises and their spread. But it is difficult to estimate the stochastic nature of cash flow constraints because of the binary, nonlinear nature of liquidity risk, and because liquidity crises in developed countries have been (until recently) rare events, so data are limited. Instead, we rely on a pragmatic approach and construct plausible rules of thumb and heuristics. These are based on a range of sources, including behavior observed during crises. This carries the advantage that it provides for a flexible framework that can capture a broad range of features and contagion channels of interest. Such flexibility can help to make the model more relevant for practical risk assessment, as it can provide a benchmark for assessing overall systemic risk given a range of solvency and liquidity shocks.

Our modeling approach disentangles the problem into distinct steps. First, we introduce a “danger zone” approach to model how shocks affect individual banks’ funding liquidity risk. This approach is simple and transparent (yet subjective) as we assume that certain funding markets close if the danger zone score crosses particular thresholds. The danger zone score, in turn, summarizes various indicators of banks’ solvency and liquidity conditions. These include a bank’s similarity to other banks in distress (capturing confidence contagion) and its short-term wholesale maturity mismatch—since the latter indicator worsens if banks lose access to long-term funding markets, the framework also captures “snowballing” effects, whereby banks are exposed to greater liquidity risk as the amount of short-term liabilities that have to be refinanced in each period increases over time. Second, we combine the danger zone approach with simple behavioral reactions to assess how liquidity crises can spread through the system. In particular, we demonstrate how liquidity hoarding and asset fire sales may improve one bank’s liquidity position at the expense of others. Last, using the RAMSI (Risk Assessment Model for Systemic Institutions) stress testing model presented in Aikman et al. (2009), we generate illustrative distributions for bank profitability to show how funding liquidity risk and associated contagion may exacerbate overall systemic risk and amplify distress during financial crises. In particular, we demonstrate how liquidity effects may generate pronounced fat tails even when the underlying shocks to fundamentals are Gaussian.

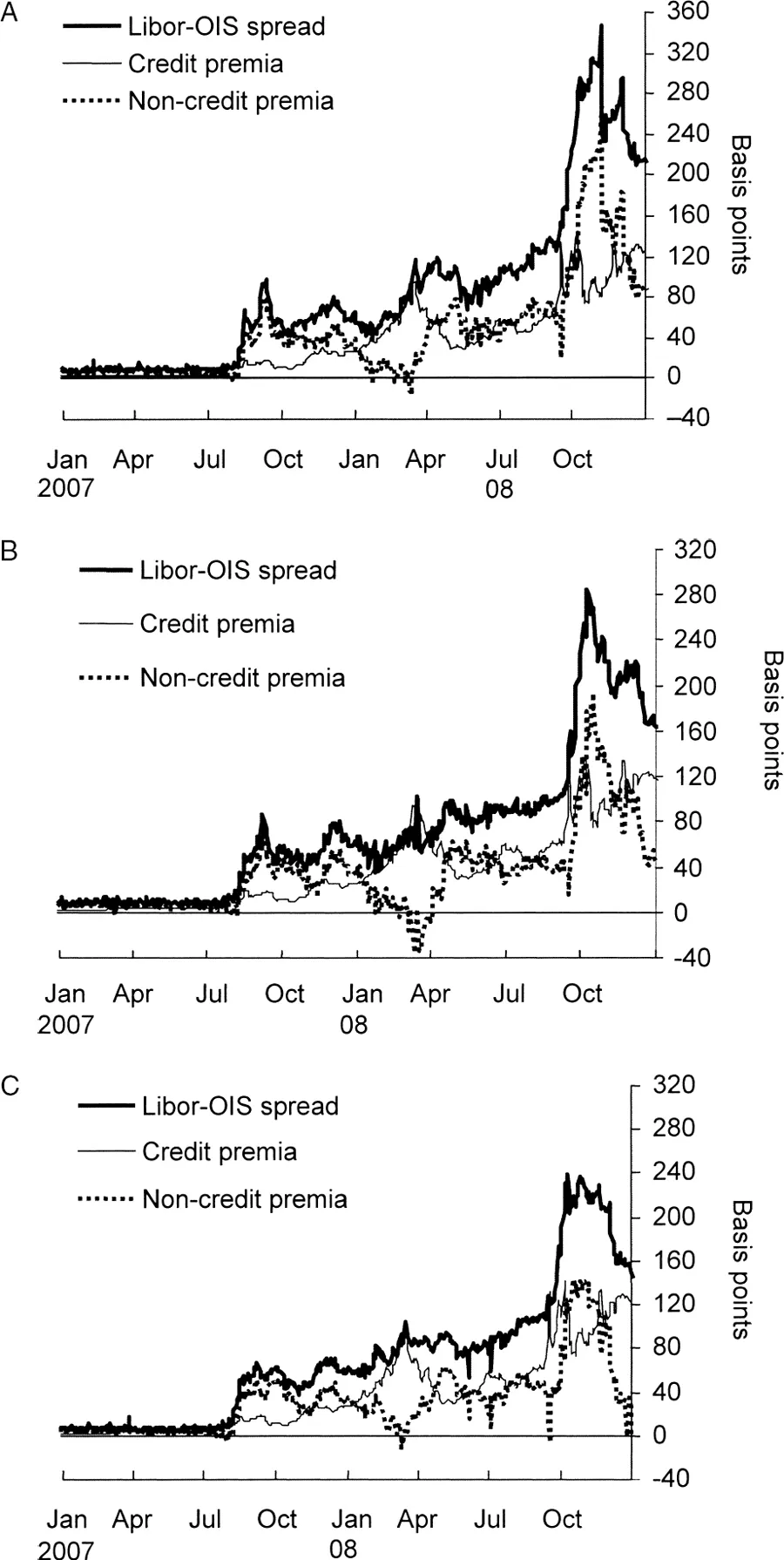

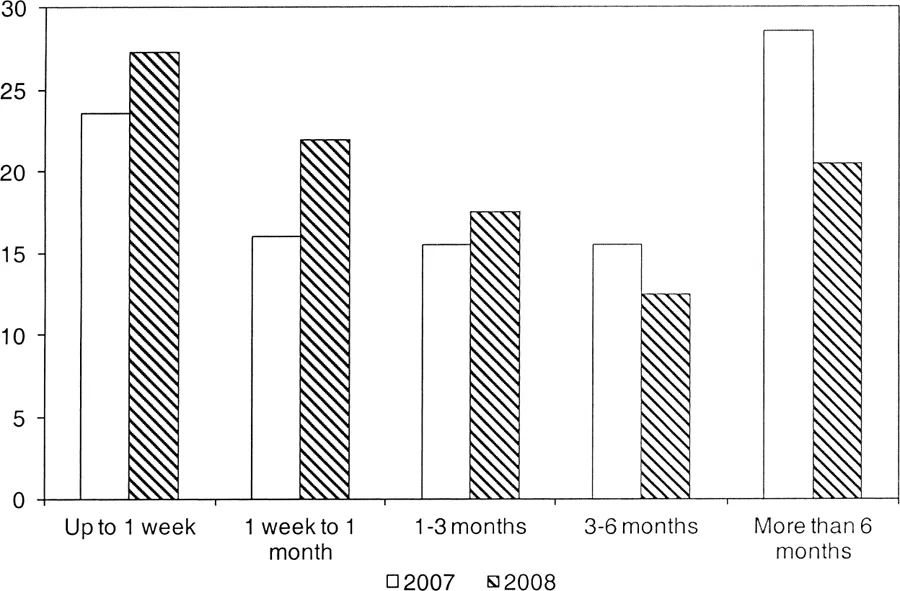

The feedback mechanisms embedded in the model all played an important role in the current and/or past financial crises. For example, the deterioration in liquidity positions associated with snowballing effects was evident in Japan in the 1990s (see figures 14 and 15 in Nakaso 2001). And in this crisis, interbank lending collapsed from very early on. Spreads between interbank rates for term lending and expected policy rates in the major funding markets rose sharply in August 2007, before spiking in September 2008 following the collapse of Lehman Brothers (figure 1.2, panels A through C, thick black lines). Throughout this period, banks substantially reduced their lending to each other at long-term maturities, with institutions forced to roll over increasingly large portions of their balance sheet at very short maturities. Figure 1.3 highlights these snowballing effects between 2007 and 2008. At the same time, the quantity of interbank lending also declined dramatically and there was an unprecedented increase in the amounts placed by banks as reserves at the major central banks, indicative of liquidity hoarding at the system level.

In principle, the collapse in interbank lending could have arisen either because banks had concerns over counterparty credit risk, or over their own future liquidity needs; it is hard to distinguish between these empirically. But anecdotal evidence suggests that, at least early in the crisis, banks were hoarding liquidity as a precautionary measure so that cash was available to finance liquidity lines to off-balance sheet vehicles that they were committed to rescuing, or as an endogenous response to liquidity hoarding by other market participants. Interbank spread decompositions into contributions from credit premia and noncredit premia (fig. 1.6, panels A through C), and recent empirical work by Acharya and Merrouche (2012) and Christensen, Lopez, and Rudebusch (2009) all lend support to this view.

It is also clear that the reduction in asset prices after summer 2007 generated mark-to-market losses that intensified funding problems in the system, particularly for those institutions reliant on the repo market who were forced to post more collateral to retain the same level of funding (Gorton and Metrick 2010). While it is hard to identify the direct role of fire sales in contributing to the reduction in asset prices, it is evident that many assets were carrying a large liquidity discount.

Finally, confidence contagion and counterparty credit losses came to the fore following the failure of Lehman Brothers. The former was evident in the severe difficulties experienced by the other US securities houses in the following days, including those that had previously been regarded as relatively safe. Counterparty losses also contributed to the systemic impact of its failure, with the fear of a further round of such losses via credit derivative contracts being one of the reasons for the subsequent rescue of American International Group (AIG).

Fig. 1.2 Decomposition of the sterling, dollar, and euro twelve-month interbank spread: A, sterling; B, dollar; C, euro

Sources: British Bankers’ Association, Bloomberg, Markit Group Limited, and Bank of England calculations.

Notes: Spread of twelve-month Libor to twelve-month overnight index swap (OIS) rates. Estimates of credit premia are derived from credit default swaps on banks in the Libor panel. Estimates of noncredit premia are derived by the residual. For further details on the methodology, see Bank of England (2007, 498–99).

Fig. 1.3 Snowballing in unsecured markets

Source: European Central Bank.

Note: Maturity-weighted breakdown for average daily turnover in unsecured lending as a percentage of total turnover for a panel of 159 banks in Europe. Based on chart 4, section 1.2 of ECB (2008).

There have been several important contributions in the theoretical literature analyzing how liquidity risk can affect banking systems, some of which we refer to when discussing the cash flow constraint in more detail in section 1.2. But empirical papers in this area are rare. One of the few is van den End (2008), who simulates the effect of funding and market liquidity risk for the Dutch banking system. The model builds on banks’ own liquidity risk models, integrates them to system-wide level, and then allows for banks’ reactions, as prescribed by rules of thumb. But the paper only analyzes shocks to fundamentals and therefore does not speak to overall systemic risk.

Measuring systemic risk more broadly is in its infancy, in particular if information from banks’ balance sheets is used (Borio and Drehmann 2009). Austrian National Bank (OeNB 2006) and Elsinger, Lehar, and Summer (2006) integrated balance-sheet based models of credit and market risk with a network model to evaluate the probability of bank default in Austria. Alessandri et al. (2009) introduced RAMSI and Aikman et al. (2009) extend the approach in a number of dimensions. RAMSI is a comprehensive balancesheet model for the largest UK banks, which projects the different items on banks’ income statement via modules covering macro-credit risk, net in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- National Bureau of Economic Research

- Relation of the Directors to the Work and Publications of the National Bureau of Economic Research

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Systemic Risk and Financial Innovation: Toward a “Unified” Approach

- 1. Liquidity Risk, Cash Flow Constraints, and Systemic Feedbacks

- 2. Endogenous and Systemic Risk

- 3. Systemic Risks and the Macroeconomy

- 4. Hedge Fund Tail Risk

- 5. How to Calculate Systemic Risk Surcharges

- 6. The Quantification of Systemic Risk and Stability: New Methods and Measures

- Notes

- Contributors

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Quantifying Systemic Risk by Joseph G. Haubrich, Andrew W. Lo, Joseph G. Haubrich,Andrew W. Lo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.