![]()

Chapter 1

First Americans, to 1550

The island’s name was Guanahaní. It shimmered in the sunlight of a calm, fragrant sea, and the sailors gazed on its palms and beaches with unspeakable relief. Their commander undoubtedly shared his men’s excitement, but he controlled himself in a dry notation to his diary. “This island is quite big and very flat,” the admiral reported. “[It has] many green trees and much water and a very large lake in the middle and without any mountains.” Allowing his feelings to escape momentarily, he added, “And all of it so green that it is a pleasure to look at it.”

Nor was Guanahaní empty. “These people are very gentle,” the admiral marveled. “All of them go around as naked as their mothers bore them. . . . They are very well formed, with handsome bodies and good faces. . . . And they are of the color of the [Canary Islanders], neither black nor white.” Certain that he had reached the outer shores of India, the explorer called the people “Indians” and their home the “Indies.” His blunder still persists.

It is no wonder that Christopher Columbus rejoiced to see green branches and gentle people on October 12, 1492. Columbus and his crew had been sailing for 33 days, westward from the Canary Islands off the west coast of Africa. They traveled in three small ships, the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria, and they were searching on behalf of the king and queen of Spain for a western passage to the fabled ports of China. No one had ever done such a thing, and they did not yet know that they had failed at their task, while succeeding at something they had never dreamed of.

The villagers who met the sailors were members of the Taíno, or Arawak, people, who uneasily shared the islands and coastlines of the Caribbean Sea with neighbors they called the Caribs. Their home lay at the eastern edge of an island cluster later called the Bahamas. We cannot know how they felt when the white sails of the little Spanish fleet loomed out of the sea that fateful morning, nor what they thought of the bearded strangers who cumbered themselves with hard and heavy clothing, and busied themselves with puzzling ceremonies involving banners, crosses, and incomprehensible speeches. The Taínos were certainly curious, however, and gathered around the landing party to receive gifts of red caps and glass beads, and to examine the Spaniards’ sharp swords. In return, the Taínos swam out to the boats with parrots and skeins of cotton thread, and then with food and water.

Neither the Taínos nor their visitors could know it, but their exchange of gifts that morning launched the beginning of a long interaction between the peoples of Europe and the Western Hemisphere. Interaction would have profound effects on both sides. The Europeans gained new lands, new knowledge, new foods, and wealth almost without measure. Tragically, the exchange brought pestilence, enslavement, and destruction to the Taínos, but Native Americans managed to survive through a tenacious process of resistance and adaptation. Interaction was unequal, but it also produced a multitude of new societies and cultures, among them the United States of America. For the Taínos as well as the Spanish, therefore, the encounter on that fateful October morning was the beginning of a very new world.

Land, Climate, and First Peoples

The Taínos of Guanahaní were among the thousands of tribes and nations who inhabited the continents of North and South America at the time of Columbus’s voyages. The Native Americans were people of enormous diversity and vitality, whose ways of living ranged from migratory hunting and gathering to the complex empires of Mexico and Peru. Each people had its own story to explain its origins, but modern anthropologists have concluded that most of their ancestors crossed a land bridge that connected Siberia and Alaska between 11,000 and 15,000 years ago.

From the Land Bridge to Agriculture

The earliest Americans traveled widely, eventually spreading across North and South America as they hunted huge mammals that are now mostly extinct: elephant species called mammoths and mastodons, wooly rhinoceroses, giant bison, horses, camels, and musk oxen. When these animals died out, they turned to other foods, according to their local environments.

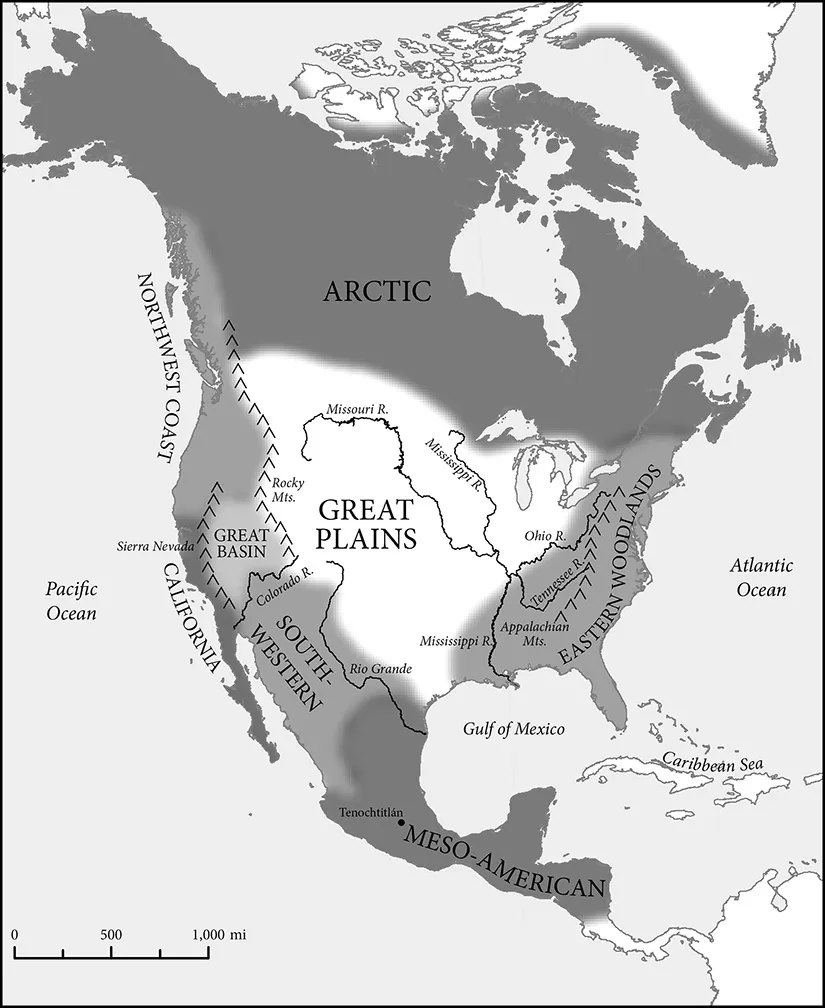

Coastal people gathered fish and shellfish. Great Plains hunters stalked a smaller species of bison (often called buffalo), and eastern forest dwellers sought white-tailed deer and smaller game. Women everywhere gathered edible plants and prepared them for meals with special grinding stones. As people adjusted to specific local environments, they traveled less and lost contact with other bands. Individual groups developed their own cultural styles, each with its own variety of stone tools. Linguistic and religious patterns undoubtedly diverged as well, as local populations assumed their own unique identities.

One of the most important adaptations occurred when women searching for a regular supply of seeds began to cultivate productive plants. The earliest Indian farmers grew a wide variety of seed-bearing plants, but those of central Mexico triumphed by breeding maize, or “Indian corn,” from native grasses about 3,000 years before the Common Era (BCE). Mexican Indians also learned to grow beans, squash, and other crops—an important improvement since the combination of corn and beans is much more nutritious than either food alone. Knowledge of corn spread slowly north from Mexico, finally reaching the east coast of North America around the year 200 of the Common Era (CE).

Agriculture brought major changes wherever it spread, and often replaced the older cultures based on hunting and gathering. Farmers had to remain in one place, at least while the crop was growing. Village life became possible, and social structure grew more complex. Artisans began making and firing clay pots to store the harvest. Baskets, strings, nets, and woven textiles made many things easier, from storing food to catching fish to keeping warm. Hunters exchanged their spears for more effective bows and arrows. More elaborate rituals appeared as planting peoples made corn the center of their religious life and made the endless cycles of sun, rain, and harvest the focus of their spiritual lives. In Mexico, farming led to village life by about 2500 BCE and supported a major increase in population.

The new tools did not spread everywhere, but Native American cultures became increasingly diverse. California Indians did not adopt agriculture, for example, but gathered bountiful harvests of wild acorns. In the Pacific Northwest, salmon and other fish were so plentiful that the Haida, Tlingit, and Kwakiutl tribes built elaborate and complex cultures based on the sea. The buffalo herds supported hunting cultures on the Great Plains. After the coming of the Spanish, tribes like the Comanche, Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa acquired European horses to pursue their prey and their enemies, laying the basis for powerful images of American Indians as mustang-riding warriors who lived in teepees made of buffalo skins.

Living very differently from the Plains Indians, four native North American cultures joined the Taínos in bearing the first brunt of the European encounter. All four depended on farming more than hunting, and all lived in permanent settlements that ranged in size from simple villages to impressive cities. The Pueblo villagers of the area that became the southwestern United States met the Spanish explorer Coronado as he wandered north seeking the mythical Seven Cities of Gold. In the future southeastern states, the mound-building Mississippian people resisted the march of Hernando de Soto, another probing Spaniard. The Woodland peoples of eastern North America received the first English explorers, from Virginians to New Englanders. And south of the future United States, the empires of Central America astonished the Spanish with their wealth and sophistication, and sharpened the invaders’ appetites for gold.

Puebloan Villagers, the First Townspeople

The introduction of agriculture brought permanent villages, with pottery making and extensive systems of irrigation, to the area that would become the southwestern United States. The earliest American townspeople lived in circular pit houses roofed against the elements, but by 700 CE they were building large, multiroom apartment houses out of stone and mud (adobe) brick. The Spaniards would later call these communities pueblos, or villages, and these Puebloan Indians built the largest residential buildings in North America until the construction of modern apartment houses in nineteenth-century cities.

The ancestral Puebloan people built some of their earliest and most elaborate structures in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, between 900 and 1150 CE. Chaco was a large and well-planned urban community, containing 13 pueblos and numerous small settlement sites, with space for 5,000–10,000 inhabitants. Linked by a network of well-made roads, the people of Chaco drew food from 70 surrounding communities. Farther north, another major Puebloan culture developed around Mesa Verde, in what is now southwestern Colorado. The Mesa Verdeans, perhaps numbering 30,000 people, built elaborate structures under cliffs and rock overhangs and also lived in scattered villages and outposts surrounding the larger settlements.

By 1300 CE, both the Chaco and Mesa Verde communities lay deserted amid evidence of warfare and brutal conflict, but refugees seem to have built new pueblos to the south and west. The Hopi and Zuñi tribes of Arizona and the modern Pueblo people of northern New Mexico are their descendants. One of their settlements, Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico, dates to 1250 CE and is the oldest continuously occupied town in the modern continental United States.

Mississippian Chiefdoms

Long before European contact, some North American Indians lived in socially and politically complex societies known as chiefdoms, with hereditary leaders who dominated wide geographical areas. The Mississippian people, as archaeologists call them, built large towns with central plazas and tall, flat-topped earthen pyramids, especially on the rich floodplains adjoining the Mississippi and other midwestern and southern rivers. Now known as Cahokia, their grandest center lay at the forks of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. At its height between 1050 and 1200 CE, Cahokia held 10,000–20,000 people in its six square miles, making it the largest town in the future United States before eighteenth-century Philadelphia. Its largest pyramid was 100 feet tall and covered 16 acres, and over 100 other mounds stood nearby. Other large Mississippian complexes appear at Moundville, Alabama; Etowah, Georgia; and Spiro, Oklahoma.

Mississippian mounds contain elaborate burials of high-status individuals, often accompanied by finely carved jewelry, figurines, masks, and other ritual objects made of shell, ceramics, stone, and copper. Long-distance trading networks gathered these raw materials from hundreds of miles away and distributed the finished goods to equally distant sites. With many similar motifs, these artifacts suggest that Mississippians used their trading ties to spread a common set of spiritual beliefs, which archeologists call the Southeastern Ceremonial Cult. With more ritual significance than practical utility, the cult’s ceremonial objects were often buried with their owners for use in the next world rather than hoarded and passed through generations as a form of wealth.

Mound construction clearly required a complex social and political order in which a few powerful rulers deployed skilled construction experts and commanded labor and tribute from thousands of distant commoners. The Spanish conqueror, or conquistador, Hernando de Soto encountered many such chiefdoms in his march across the American southeast between 1539 and 1541. Survivors from his expedition described large towns of thatched houses, surrounded by strong palisades and watchtowers. Borne on a cloth-covered litter, the queen of a major town called Cofitachique showed de Soto her storehouses filled with carved weapons, food, and thousands of freshwater pearls. Almost two centuries later, French colonists in Louisiana described the last surviving Mississippian culture among the Natchez Indians. Their society was divided by hereditary castes, led by a chieftain called the “Great Sun,” and included a well-defined nobility, a middling group called “Honored People,” and a lower caste called “Stinkards.” As in Mexico and Central America, the Natchez pyramids were sometimes the scene of human sacrifice.

Wars and ecological pressures began to undermine the largest Mississippian chiefdoms before de Soto’s arrival, and epidemics apparently depleted most of the others by the time English colonizers arrived in the seventeenth century. The survivors lived in smaller alliances or even single towns without large mounds or powerful chiefs, but governed themselves by consensus. They also coalesced in larger confederacies when necessary; Europeans would know them as Creeks or Choctaws.

Woodland Peoples of the East

On the Atlantic coast, Eastern Woodland Indians lived by a combination of hunting, fishing, and farming, and dominated the area when the Mississippians declined. Woodland women had developed agriculture independently, by cultivating squash, sunflowers, and other seed-bearing plants as early as 1500 BCE. They adopted corn around 900 CE and added beans and tobacco.

Woodland Indians practiced a slash-and-burn agricultural technique, in which men killed trees by cutting the bark around their trunks and then burned them to clear a field. Women then used stone-bladed hoes and digging sticks to till fertilizing ashes into the soil and to plant a mixed crop of corn and beans in scattered mounds. When the field’s fertility declined, the villagers would abandon it and clear another, returning to the original plot when a long fallow period had restored its fertility. Anthropologists have found that slash-and-burn agriculture is very efficient, generating more food calories for a given expenditure of energy than more modern techniques, but it obviously requires ample territory to succeed in the long run.

Woodland Indians lived in semipermanent villages for the growing season. They made houses from bent saplings covered with bark, mats, or hides, and sometimes surrounded their villages with log palisades. During the fall and winter, men frequently left their villages for extended hunting trips. Spring could bring another migration to distant beds of shellfish or to the nearest fishing ground. Coastal peoples developed complex systems of netting, spearing, and trapping fish later copied by Europeans. With appropriate variations according to climate and other conditions, this way of life prevailed extensively up and down the Atlantic coast, from Florida to Maine.

Woodland villages ranged in size from 50 inhabitants to as many as several hundred. Adjacent villages usually spoke the same language, and several large families of languages prevailed across most of eastern North America: Algonquin on the Atlantic coast and around the Great Lakes, Iroquoian in the Hudson River Valley and parts of the south, Muskogean in the southeast. Europeans usually referred to the speakers of a common language as members of a “nation” or “tribe,” but the Indians themselves did not feel the same degree of political unity that the Europeans expected of them. Village chiefs normally ruled by custom and consent, and individual clans and families were responsible for avenging any injuries they received. Related tribes might come together in confederacies, like the League of the Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee, in western New York or the Powhatan Confederacy of Chesapeake Bay, but these loose-knit federations needed charismatic leadership and continual diplomacy to hold them together. Each tribe claimed its own territory for hunting and tillage, and specific plots belonged to different families or clans, but tribes owned their lands in common and individuals did not buy or sell land privately. Like the Mississippians and most other Native Americans, Woodland peoples traded raw materials and finished goods, including strings or belts of shell beads called wampum, over wide areas, and cherished fine objects for their manitou, or spiritual power. These exchanges were not barren commercial transactions but forms of reciprocal gift giving that bound the givers into valued social relationships ranging from loyalty between leaders and their supporters to alliances between towns.

Woodland men were responsible for hunting and war, while women took charge of farming and childcare. Most Woodland Indians practiced matrilineal kinship, which meant that children belonged to the families and clans of their mothers. In contrast to the women of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European societies, Indian women took an active role in political decision making and often made critical decisions regarding war or peace as well as the fate of military captives.

Woodland tribes fought frequent wars against one another, but usually not to expand their territories. Instead, warriors gained personal honor by demonstrating bravery and avenging old injuries. They might adopt their captives to replace lost relatives, or torture them to death to satisfy the bereaved. Native warfare changed dramatically after the Europeans arrived, as some Woodland tribes fought for favorable positions in the fur trade or sold their prisoners to the colonists as slaves.

The Empires of Central and South America

The most spectacular civilizations in precolonial North America emerged in Mexico and Central America, also called Mesoamerica. When the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century, many Mesoamericans lived in cities that dwarfed the capitals of Europe, with stone palaces and pyramids that provoked the newcomers’ envy and amazement. Mayas and Aztecs made gold and jeweled objects of exquisite beauty, cloaked their leaders in shimmering feathered robes and luxurious textiles, and recorded their deeds in brilliantly colored books. It was an impressive record of power and material achievement, but the Spanish destroyed most of it in their zeal to stamp out the Indians’ religion and amass their treasure. What we now know about these civilizations comes from reports by the conquerors and a few survivors, from archeology, and from the painstaking decoding of surviving inscriptions.

Mesoamericans began living in cities as early as 1200 BCE, but the cultures who met the Spanish had appeared more recently. In Yucatán and adjoining areas of Central America, the Mayan people built numerous city-states between 300 and 900 CE, with a total population of some five million. Each city featured one or more stone temples and a hereditary nobility supported by tribute from peasants. The Mayan city-states made frequent wars on their neighbors to obtain more tribute and to capture victims for sacrifice atop their dizzying pyramids. They also devised the only written language in the Americas before European contact and used a precise calendar to record key dates from the reigns of their kings. Unlike the ancient Romans, Mayan mathematicians used a zero in their calculations and accurately measured the movement of heavenly bodies. Though remnants of elite Mayan culture persisted until the era of the Spanish conquest, the Mayas abandoned most of their cities for unknown reasons by about 950 CE.

The Aztecs (or Mexica) were the most powerful people the Spanish conquerors met in the sixteenth century. About 1325 CE, ancestors of the Aztecs migrated to the central valley of Mexico and founded the city of Tenochtitlán on an island in a lake there. By 1434, Tenochtitlán had become the domi...