![]()

1

Happiness, Affluence, and Altruism in the Postwar Period

Frank Levy*

1.1 Happiness, Affluence, and Altruism

If an economist were asked to assess U.S. postwar economic performance, he would probably describe the period in three intervals:

The late 1940s and 1950s were fairly good. Real wages grew very quickly. The period had three recessions but only the last one (1958–60) was severe. Inflation was low except when WW II price controls were lifted and when the Korean War began. When inflation was a problem, a year of recession was sufficient to end it.

The 1960s were better. Real wages did not grow quite as fast in the 1950s but recessions were less of a problem. After 1963, the economy went on a sustained expansion. Unemployment fell more or less continuously until 1970. And inflation did not really emerge until the end of the decade.

The 1970s were awful. The 1960s expansion left an inflationary inertia so that the 1970–71 recession was not enough to bring inflation under control. Then came the 1972–73 food price explosion and the first OPEC price rise. They generated supply-shock inflation that was even more immune to recession. After 1973, productivity stopped growing and real wages stagnated. And then there was another OPEC price rise to finish out the decade. It was terrible.

The assessment appears non-controversial, yet it contains a large piece of thin ice. Terms like pretty good, better and awful imply something about not only the economy but about how people reacted to the economy. One could read the assessment as saying that people were happier in the 1960s than in the 1950s and least happy in the 1970s.

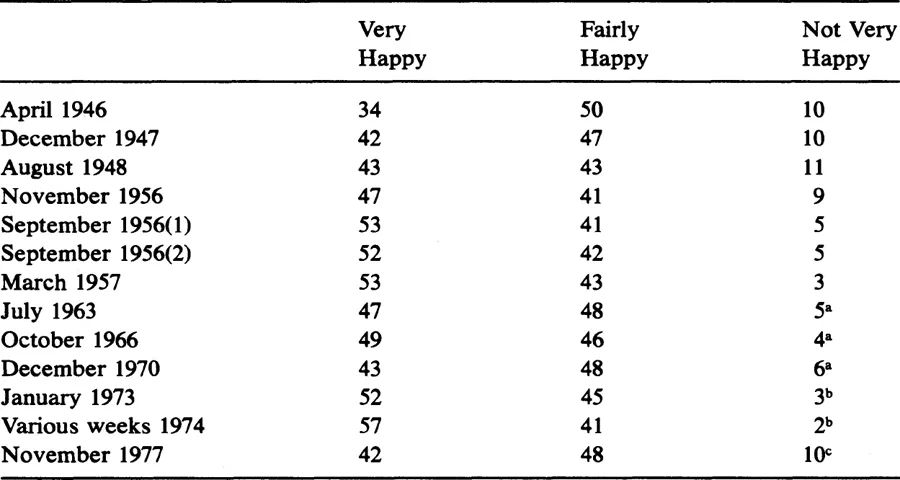

The most direct evidence of this proposition does not offer strong support. Periodically, the Gallup poll (officially the American Institute of Public Opinion—hereafter AIPO) asks questions with the following general form (e.g., AIPO 410): In general, how happy would you say that you are—very happy, fairly happy, or not very happy?

Responses to this question are contained in table 1.1. Data for the early postwar years through 1957 show a moderately increasing level of happiness—a possible reflection of rising real incomes. Then a six-year gap occurs during which time the question was not asked. When the data resumes in 1963, a trend is harder to discern. Interpretation is difficult because the precise wording of the question changes in 1963, 1973, and again in 1977. Moreover the 1977 response—the happiest in the series—comes from a poll that focused on religious habits and beliefs; responses for other years come from polls that focused on politics and the economy. When adjustments are made for these problems, the data suggest that the moderately rising level of happiness through the 1950s was followed by a roughly constant level of happiness thereafter.

Table 1.1 Distribution of Responses to AIPO Question

| Very Happy | Fairly Happy | Not Very Happy |

April 1946 | 34 | 50 | 10 |

December 1947 | 42 | 47 | 10 |

August 1948 | 43 | 43 | 11 |

November 1956 | 47 | 41 | 9 |

September 1956(1) | 53 | 41 | 5 |

September 1956(2) | 52 | 42 | 5 |

March 1957 | 53 | 43 | 3 |

July 1963 | 47 | 48 | 5a |

October 1966 | 49 | 46 | 4a |

December 1970 | 43 | 48 | 6a |

January 1973 | 52 | 45 | 3b |

Various weeks 1974 | 57 | 41 | 2b |

November 1977 | 42 | 48 | 10c |

Source: Various AIPO polls.

Note: The AIPO question reads: “In general, how happy would you say you are—very happy, fairly happy, or not very happy?”

aRead “not happy” rather than “not very happy.”

bRead “not at all happy” rather than “not happy.”

cRead “not too happy” rather than “not very happy.”

Ten years ago, Richard A. Easterlin (1974) wrote an ingenious essay interpreting these poll responses in the context of James Duesenberry’s relative income hypothesis (Duesenberry 1952). Easterlin began by noting that within any poll, higher-income individuals were more likely than lower-income individuals to report themselves as happy. He contrasted this association with his perception of a weaker association over time when real incomes were rising for everyone. He also examined data from Cantril’s cross-national study (Cantril 1965) which showed a similar lack of association between a country’s per capita income and the self-reported happiness of its population.

Together these data provided Easterlin with a basis for an application of the relative income hypothesis. In the application, an individual’s happiness depends on the relationship between his income and his needs, but his needs are heavily conditioned by what he sees around him. If incomes were to rise uniformly, an individual’s relative position (apart from lifecycle considerations) would remain unchanged, and so his individual happiness would not increase.

Easterlin’s argument is appealing but it raises two problems. First, it does not explain the rising level of happiness in the early postwar years. Second, it leads to an overemphasis of private, versus public, consumption. As Easterlin writes:

Finally, with regard to growth economics, there is the view that the most developed economies—notably the United States, have entered an era of satiation. . . . If the view suggested here has merit, economic growth does not raise a society to some ultimate state of plenty. Rather, the growth process itself engenders ever-growing wants that lead it ever onward. (1974, p. 121)

In the Easterlin-Duesenberry argument “ever-growing wants” refers to additional private consumption. It is private consumption, after all, that provides one’s easiest comparisons with one’s neighbors. But the focus on private consumption ignores important history.

The largest omission is the growth of the public sector. In 1947, all government nondefense outlays accounted for 14 percent of GNP. By 1980 these outlays had grown to 28 percent of GNP. In explaining this growth, the mid-1960s emerge as a particularly pivotal period during which the federal government instituted health insurance for the aged, the War on Poverty, aid to elementary and secondary schools (with emphasis on compensatory education) and other areas, which significantly redefined the role of the public sector.

To be sure, these Great Society years were distinguished not so much by growing expenditures as by new initiatives that would obligate future expenditures. Administration officials occasionally acknowledged the problems they were creating for future administrations. But they felt they had a rare opportunity, a narrow window, during which they had to finish what the New Deal had left undone (Moynihan 1967; Sundquist 1968).

Their opportunity came from a particularly sympathetic public. When government officials of the time proposed a new initiative, they emphasized its “public good” aspects: the way in which aiding the poor, the elderly, or the disadvantaged would make the United States a more humane place for everyone. Consider, for example, Lyndon Johnson’s eloquent Howard University speech on equality for blacks:

. . . There is no single easy answer to all of these problems.

Jobs are part of the answer. They bring the income which permits a man to provide for his family.

Decent homes in decent surroundings, and a chance to learn—an equal chance to learn—are part of the answer.

Welfare and social programs better designed to hold families together is part of the answer.

Care of the sick is part of the answer.

An understanding heart by all Americans is also a large part of the answer.

To all these fronts—and a dozen more—I will dedicate the expanding efforts of the Johnson Administration.

. . . This is American justice. We have pursued it faithfully to the edge of our imperfections. And we have failed to find it for the American Negro.

It is the glorious opportunity of this generation to end the one huge wrong of the American Nation and, in so doing, to find America for ourselves, with the same immense thrill of discovery which gripped those who first began to realize that here, at last, was a home for freedom. (Quoted in Rainwater and Yancey 1967, pp. 131–32)

The rarity was not in Johnson’s argument,1 but in the number of people who agreed with it. While the majority of the population did not demand such initiatives, they did form, in V. O. Key’s phrase, a “permissive consensus” that allowed the government to implement its liberal agenda (Key 1961, p. 33). This willingness to experiment with public consumption (in hopes of increasing the general welfare) is not contained in Easterlin’s reading of Dusenberry’s theory. In this paper, we view the origins of the mid-1960s consensus from a somewhat different perspective.

A sensible explanation of the mid-1960s must account for both the origins of public consensus and its subsequent demise. By most estimates, the consensus for new initiatives peaked in 1964–66 and then began to erode. Government, acting in part on inertia, produced occasional new programs through the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the universalization of food stamps (1971) and the federal take-over of aid to the aged, blind, and disabled (1972) marking the end of the period. The remainder of the 1970s was increasingly dominated by antigovernment and antitax sentiment.

History affords few natural experiments; thus it is not surprising that the mid-1960s consensus has attracted a variety of explanations. The origin of consensus has been ascribed to the growth of the civil rights movement, and to the combination of John Kennedy’s assassination and Barry Goldwater’s candidacy (Sundquist 1968). The end of consensus has been ascribed to the devisiveness of the Vietnam War and to Watergate. But while all of these explanations sound plausible, none by itself is sufficient.

Consider, for example, the combined effects of the Kennedy assassination and the Goldwater candidacy. They were traumatic experiences that led to a Democratic president and Democratic congressional majorities. A rough parallel existed ...