![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Enchanted (Post) Modernity

This book began as an attempt to make sense of some of the systems of belief which were current in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, but which no longer enjoy much recognition today. Astrology, witchcraft, magical healing, divination, ancient prophecies, ghosts and fairies, are now all rightly disdained by intelligent persons.

KEITH THOMAS, Religion and the Decline of Magic, 1971

The postmodern condition is nevertheless foreign to disenchantment.

JEAN-FRANÇOIS LYOTARD, La condition postmoderne, 1979

If you were to travel to the small town of Kotohira on the Japanese island of Shikoku, you might, after strolling past one of the country’s oldest Kabuki theaters and partaking of the region’s famous udon noodles, find yourself at a famous shrine, the town’s central attraction for tourists and pilgrims.1 There, on the grounds of this ancient site, you would find a dedicatory plaque sporting a very modern image, that of Japan’s first cosmonaut, AKIYAMA Toyohiro, clad in a spacesuit standing next to his craft. Despite its space-age content, however, the plaque gives thanks to Konpira, the so-called god of sailors, for Akiyama’s safe voyage through interplanetary space. This confluence of technology and public religiosity is by no means unique to the Konpira Shrine. Analogous examples dot the Japanese cultural landscape. As I have argued elsewhere, generally speaking, recent Japanese history meant changes in the locus of enchantment, in ways unanticipated by classical theorists of modernity.2 In one of the most technologically and scientifically advanced nations today, one finds—in addition to old-fashioned faith healers and spirit mediums—flash drives that double as magical charms, funeral rituals for old photographs and discarded electronics, iPhone apps for automatic exorcisms or traditional fortune-telling, and Buddhist stupas dedicated to Thomas Edison and Heinrich Hertz as the “Divine Patriarchs of Electricity and Electro-Magnetic Waves.”3

Despite the Orientalist cliché of a mystical Asia, Japan does not have a monopoly on contemporary enchantments. In study after study, scholars of the Global South have charted not only traditional but modern forms of magic, including: Internet-based virtual Haitian Vodou; epidemics of spirit possession among Malaysian factory workers; clairvoyant Brazilian spirit surgeons; modern witchcraft persecutions in South Africa and Indonesia; Vietnamese divinities that are appeased with cans of Coke and Pepsi; aerosol sprays to evoke the protection of Santísima Muerte in Mexico; gun-toting spirit mediums in Uganda; an Indian guru supposedly capable of magical materializations, faith healing, and even bringing people back from the dead; and a notorious pair of demonically possessed underpants in Ghana.4 It would seem that Latin America, Africa, and indeed most of Asia are inhabited by sorcerers and alive with spirits.

While lingering enchantments used to be taken as a rationale for the backwardness of non-European others, today they are often regarded as evidence that the disenchantment model is an uncomfortable fit outside the land of its birth. Hence contemporary scholars like Denis Byrne explicitly reject “the common assumption that post-Reformation disenchantment encompasses the non-European world.”5 While I agree with Byrne’s sentiment as far as it goes, in this short chapter I want to challenge the idea that disenchantment is the order of the day even in the so-called heartland of modernity.

WEIRD AMERICA

There is a constant war between the messengers of God and ghosts and demons, dancers and drinkers, and, for all anyone knows, between God’s messengers and God himself—no one has ever seen him, but then no one has ever seen a cuckoo either. . . . Here is a mystical body of the republic, a kind of public secret: a declaration of what sort of wishes and fears lie behind any public act, a declaration of a weird but clearly recognizable America.

GREIL MARCUS, The Old, Weird America, 2011

It is hard not to be skeptical of claims to disenchantment as I write these words in a café adorned with flyers advertising “crystal healing,” “energy balancing,” “chakra yoga,” and “tarot” readings.6 Undeniably, what Catherine Albanese and Courtney Bender refer to as American “metaphysical religion” would seem to be on display in coffee shops, co-ops, and bookstores throughout the country.7 Moreover, in Europe and America, films, novels, and television series continue to overflow with magic, providing symbolic resources—what Christopher Partridge and Jeffrey Kripal refer to as “occulture”—that are often recouped by this religious counterculture (e.g., rituals appearing first in Buffy the Vampire Slayer are adopted by contemporary Wiccan covens).8 It would seem that many of the stories we tell ourselves in the modern West are about superheroes and magicians, ghosts and monsters, and that these creatures often spill over into other parts of the culture. As Kripal observes in regard to the seeming ubiquity of such cultural materials: “The paranormal is our secret in plain sight.”9

Even setting aside the abundance of explicitly fictional forms of enchantment, studies of American reading habits similarly suggest that “New Age” print culture has “expanded exponentially in the past thirty years” with “non-fiction books” about magic, guardian angels, and near-death experiences appearing in the upper echelons of Amazon’s best-seller lists.10 Moreover, the last ten years have seen a proliferation of “reality” television series that claim to report evidence for ghosts, psychics, extraterrestrials, monsters, curses, and even miracles.11 In both the United Kingdom and the United States, it is also easy to turn on the television and encounter the prognostications of celebrity psychic mediums.12 It might seem that contemporary audiences are at least willing to flirt with the existence of spirits and the supernatural.

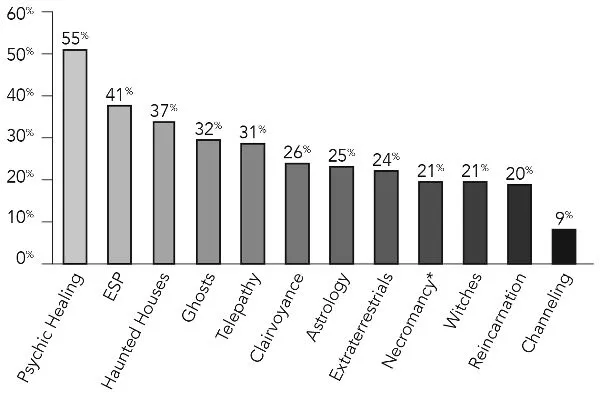

A variety of sociological evidence would seem to support this intuition. In 2005, Gallup conducted a telephone survey with 1,002 American adults asking them if they believed in things like ESP, ghosts, telepathy, and witches (see figure 1). Not only did a surprising number of the American respondents reportedly believe in each of these (e.g., almost a third believe in ghosts), but also other polling firms, while not covering identical beliefs, have produced similar numbers.13 For a recent example, a YouGov 2015 survey of 1,171 Americans showed that 48 percent of those sampled agreed with the claim “Some people can possess one or more types of psychic ability (e.g., precognition, telepathy, etc.),” while 43 percent agreed with the statement “Ghosts exist.”14 Even slight differences in the wording produce different responses, but taken together it appears the majority of Americans are at least open to the idea of ghosts and psychic powers, while a not-insignificant number believe in necromancy.

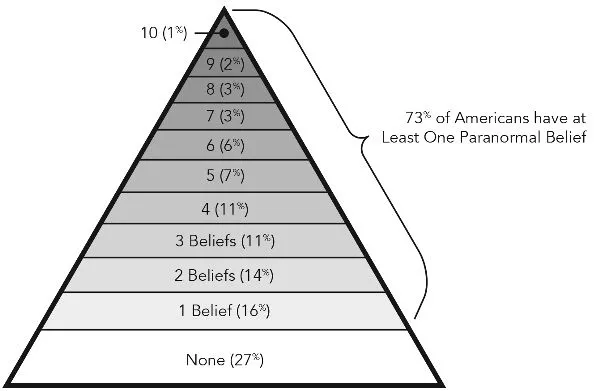

Remarkably, if one takes a closer look at the Gallup 2005 polling data, it shows something even more interesting: belief in different forms of the “paranormal” (see note for terminology) are not confined to a single subculture.15 For example, believers in telepathy and witchcraft are likely only semi-overlapping sets because, as the survey indicated, 73 percent of those responding believe in at least one of the poll’s ten paranormal categories (see figure 2).16 Although it might sound shocking, this percentage is nearly identical to earlier iterations of the Gallup poll from 2001 and 1990.17 The implications of these statistics are worth underscoring because, if this data is accurate, it means that only approximately a quarter of Americans are not believers in the paranormal. We live in a land of wonders in which most people are believers and skeptics are the clear minority.

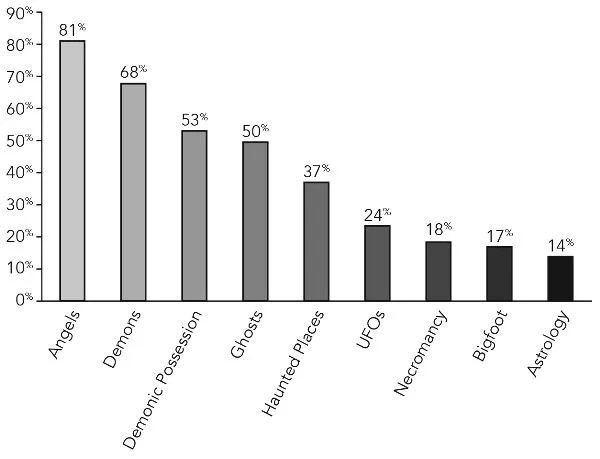

It might be tempting to discount these polls as mere journalistic sensationalism, but sociologists have found similar results. In 2005 and 2007, sociologists at Baylor University conducted a fairly robust set of phone interviews (sample size of 3,369) from across the United States. Their main focus was a complete picture of American religious beliefs, but a similar pattern emerges (see figure 3).18 Again we see evidence that about half of the American population believes in ghosts, while a clear majority believes in demonic possession. This latter claim accords with the fieldwork of the American sociologist Michael Cuneo, who in 2001 suggested that belief in demonic possession was not only widespread, but also on the increase such that “exorcism is more readily available today in the United States than perhaps ever before.”19 Moreover, in a section of the 2007 survey not depicted in figure 3, 55 percent of those polled claimed they had personally experienced being “protected from harm by a guardian angel.”20 In sum, the picture painted by the Baylor study is one of an America enthusiastically engaged with angels, demons, and other invisible spirits.21

Sociologists Christopher D. Bader, F. Carson Mencken, and Joseph O. O. Baker published an analysis of relevant portions of the Baylor data in Paranormal America (2010), which they combined with fieldwork interviewing self-described psychics and Bigfoot hunters. Bader, Mencken, and Baker ultimately summarize their findings in strong terms:

The paranormal is normal. . . . Statistically, those who report a paranormal belief are not the oddballs; it is those who have no beliefs that are in the significant minority. Exactly which paranormal beliefs a person finds convincing varies, but whether it is UFOs and ghosts or astrology and telekinesis, most of us believe more than one. If we further consider strong beliefs in active supernatural entities and intense religious experiences the numbers are even larger.22

In sum, Bader, Mencken, and Baker also estimate that more than two-thirds of Americans believe in the paranormal.23

Demographic trends can also be extracted from the data as specific paranormal beliefs can be identified with different populations. For example, African American women were the most likely to believe in ghosts and the possibility of communication with the dead, while Caucasians were more likely to believe that they have been abducted by extraterrestrials.24 But believing in at least one form of the paranormal is not confined to a particular counterculture and is evidently the norm throughout the country.

Nor has it vanished with compulsory mass education. While there is a connection between education and specific paranormal beliefs, there is little correlation between level of education and having paranormal beliefs as such. For instance, Bader, Mencken, and Baker conclude that college graduates are less likely to believe i...