![]()

ONE

“From ‘Dragon Bones’ to Scientific Research”: Peking Man and Popular Paleoanthropology in Pre-1949 China

Celestial Clouds and Zip Wires

In 1934, a dynamite blast during the excavation of the Peking Man fossils destroyed the Temple of the Hill God (

) at Zhōukŏudiàn.

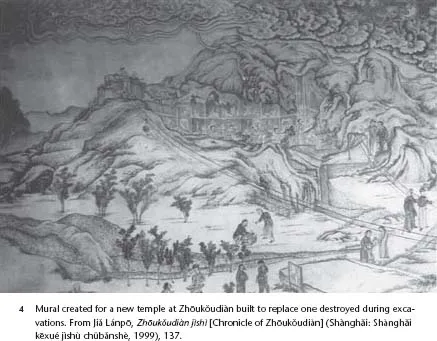

1 The scientists involved in the research arranged for a new temple to be built, but in place of the original mural portraying a deity they installed one that vividly evoked the complex social and cultural milieu of the time (

figure 4). Composed in a recognizable style of Chinese landscape painting, the new mural retained the swirling clouds that connote the divine in Daoist representations and a narrative element commonly seen in Chinese art. Yet the subject matter was thoroughly modern: it depicted the scientific excavation work then in progress at the site. Prominently featured was the zip wire installed to facilitate the transport of baskets of excavated rock and

gravel, of which participants were duly proud.

2 Also visible in the painting were the many types of people who participated in the excavation and in daily life in the surrounding community. Workers dug in the excavation pit, which was marked in sections with Roman letters, and filled baskets with material to be sent down the wire. Scientists in Chinese and Western clothes—although interestingly no obvious examples of Western scientists—observed the work. Women in Chinese dress walked up the road to the site, while a man at the bottom sold food out of a basket to a customer. Two other women stood reading a sign that identified the site and the scientific work underway.

Through its inclusions, and also its omissions, the mural captured much of what defined the work at Zhōukŏudiàn and what it meant for Chinese society at large. It expressed the hope that China could become modern without losing its Chinese “essence,” and that Chinese and Westerners—or at least their clothing—could work together toward a common goal while respecting Chinese leadership in China. It was significant that the goal in question, along with the means for achieving it, was science—an international endeavor in which Chinese people were struggling to participate as equals. But not all Chinese could be equals: whether in Chinese robes or Western suits, scientists could be distinguished from the workers who handled the heaviest and least rewarding jobs. Finally, the painting appeared to symbolize simultaneously the replacement of religion with science and also the accommodation of science to existing Chinese ideas and practices, including spiritual ones. Having blown up the original temple, scientists replaced it with an altar to science and a depiction of themselves as the principal agents in the transformation. The human power of science represented by the zip wires, however, appeared nonetheless as an extension of the power of heaven coming to earth through the ribbons of clouds on which immortals were often seen to descend. These core relationships—nationalism and internationalism, elite and worker, tradition and modernity, science and “superstition”—were to continue to frame popular paleoanthropology throughout the twentieth century.

A Willingness to Change

An adage from the ancient classic, the Book of History (

), has often been called upon in China to express the nature of the human:

3. Pithy and potent, this quotation (which serves as the epigraph to this volume) is also open to diverse interpretations—qualities that help explain its continued cultural significance.

is “human”;

is “the ten thousand things.” The difficulty is with

(

líng). It typically refers to a spiritual essence or quality. It may denote a female shaman, a divinity, the soul, the austerity of a leader, the quality of being efficacious, innate intelligence, fortune, or excellence.

4 The adage has been translated into English as “man is the soul of all creation,” “man is the best of the ten thousand things,” and “of all creatures, man is the most highly endowed.”

5 An equally plausible translation would be “humans are the intelligent ones of the ten thousand things.” The connotations

of intelligence and leadership led Japanese and Chinese intellectuals to use

(efficacious leader) to translate the term “primate” in their writings on biology and evolution. This was probably the sense that Máo Zédōng had in mind when in a 1964 speech he said: “In the past, they said…‘

’ Who called a meeting to elect [humans to this position]? They appointed themselves.”

6Darwin is often credited with promoting the radical principle that humans are animals. In the century since Darwinism was first introduced to China, the ancient adage from the Book of History has appeared to different people either as prescient or as old fashioned, depending on whether they have understood it to acknowledge the place of humans among other living things or to emphasize their exceptional qualities. For one famous advocate of science in 1921, the spiritual quality of the term

was problematic, and he contrasted it with the evolutionary perspective then taking Chinese intellectuals by storm: “People who consider themselves ‘the spirit of the ten-thousand things’ have forgotten that they are still biological organisms.” It was only by “knowing themselves” as such that the Chinese people could achieve a “true self-liberation movement.”

7Actually, it is an ancient notion, in China and elsewhere, that the boundary between humans and animals is porous. Chinese writings throughout imperial times abounded with tales of creatures part human, part animal, and others—like fox spirits and snakes—that could change into human form and back again. The “hairy people” (

are a late example: they appear in a Qīng dynasty (1644–1911) gazetteer and in the writings of the eighteenth-century folklorist Yuán Méi. Legend has it that they descended from people who had fled conscript labor on the first Qín emperor’s Great Wall; removed from the civilizing influences of society, they had reverted to beasts.

8 According to classical Chinese texts, humans were originally not separate from the animals; they achieved humanity only through the actions of the sage kings.

9 If the classics told that humans had originated among the beasts, they also suggested that

humans could slip back across the boundary if they abandoned that which distinguished them—namely, their moral sensibilities and adherence to ritual.

10 By the same logic, members of ethnic groups whose customs differed were often classified along with the “wild beasts.”

11 What made Darwinism as introduced to China such a powerful new idea was not simply the placement of humans within the natural world, but the law of progressive change that went with it.

12 When Peking Man arrived on the scene, she would be understood as part of this forward momentum and not, like the “hairy people,” as an example of slipping back across the boundary into the realm of animals. While in Chinese folklore the possibility of transformation between animal and human was two-way, in modern evolutionary theory, movement is one-way. Humans

were like the rest of the animals but have evolved and cannot go back.

The first to write on human evolution in China were not scientists. They were officials and intellectuals who sought to make sense of the related experiences of a declining Qīng empire, encroaching imperialist powers, and an emerging Chinese nationalism. In the writings of Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, Herbert Spencer, Pyotr Alekseyevich Kropotkin, and others, Chinese writers in the first half of the twentieth century hoped to find answers to the questions Why is China weak? and How can China be made strong?

The man most responsible for introducing Darwinian thought to China was Yán Fù (1853–1921), an educator and Westernizer who in 1898 published a paraphrastic and heavily annotated translation of Thomas Huxley’s

Evolution and Ethics (1893), entitled in Chinese

On Evolution (

)

13 Yán’s motivation for writing the text and the reason for its widespread influence was the apparent relevance of the subject to “self-strengthening and the preservation of the race.”

14 It was not Darwinism per se, but social Darwinism, that interested Yán and his many followers,

including the notable reformer Hú Shì (1891–1962), who adopted the character

for his given name to evoke the phrase “survival of the fittest” (

).

15Yán drew selectively from both Herbert Spencer and Thomas Huxley to generate a vision of evolution suitable for a Chinese reformer of his era. Yán adopted Spencer’s optimism with respect to evolution as a progressive force while rejecting his individualism and his willingness to forego human action for the betterment of society. Huxley proved the perfect complement: eschewing Huxley’s pessimistic view of evolution as a necessarily brutal force, Yán nonetheless embraced Huxley’s call for people to organize to improve themselves and their societies physically, intellectually, and morally.16

Yán’s synthesis, like the new painting in the Temple of the Hill God, marked both an accommodation to long-standing Chinese beliefs and a reorientation to a modern notion of progressive change. Considering human ethical action an essential part of the struggle for existence left room for Confucian activism. It also preserved what had long been held in China to be the crucial distinction between humans and animals, their understanding of morality and their ability to manifest it through correct practice—in short, their humaneness (

).Moreover, Yán’s sense of a cosmic pattern governing nature and human society strongly resonated with Daoist ideas.

17At the same time, Yán’s Darwinism was progressive. Unlike the two-way movement between human and animal found in Chinese legends, in the evolutionary theory that Yán introduced the position of animals became fixed in the human past as “ancestors”—a concept bound to make many filial Chinese somewhat uncomfortable. Looked at in the other direction, however, the struggle for existence moved nature and society ever closer to perfection. Yán found in evolutionary theory the lesson he thought China most needed to learn. Change was both unavoidable and beneficial. To survive and prosper, China had to embrace change and release the progressive energies of the people that had been inhibited by ignorance, poverty, and weakness.18

Thus, Yán Fù and his followers were also voluntarists. For the problems that concerned late Qīng-dynasty scholars—national strength in the face of imperialism and above all the need for modernizing change—continued to occupy their successors through the disunity, war, and revolution that filled the republican era (1912–1949). In a 1927 speech at Whampoa Military Academy, the famous Chinese writer Lŭ Xùn offered this interpretation of human origins: “Why did men become men, and monkeys remain monkeys? This was simply because monkeys were unwilling to change—they liked to walk on all fours.”19 This was the dominant understanding of evolution in China when Peking Man stepped on the scene in the late 1920s, and it remained powerful for many decades to come. Significantly, the same volu...