![]()

1

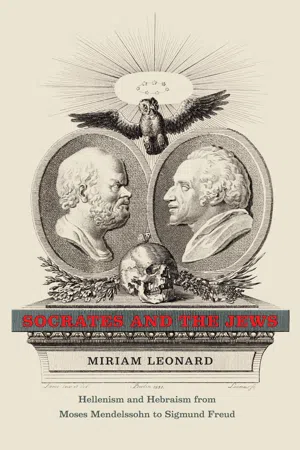

Socrates and the Reason of Judaism: Moses Mendelssohn and Immanuel Kant

“There must be Jews who are not really Jews.”

LESSING, Die Juden

In September 1784 the Berlinische Monatschrift published an answer to the question “What is Enlightenment?” The essay was written by the Berlin philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Immanuel Kant’s more celebrated answer to that same question, published in the same journal three months later, “marks” what Foucault has called “the discreet entrance into the history of thought of a question that modern philosophy has not been capable of answering, but it has never managed to get rid of, either.”1 “With the two texts published in the Berlinische Monatschrift” continues Foucault, “the German Aufklärung and the Jewish Haskala recognize that they belong to the same history; they are seeking to identify the common processes from which they stem. And it is perhaps a way of announcing the acceptance of a common destiny—we now know to what drama that was to lead.”2

Foucault locates the beginning of a new philosophical era, indeed the beginning of modernity itself, in the collocation of these two essays, Kant’s and Mendelssohn’s, by the coincidence of the projects of the Aufklärung and the Haskalah. But, in Foucault’s engagement with the question of Enlightenment, his own meditation on the destiny of a German and Jewish injunction to think soon gives way to an exclusive focus on Kant’s work. If Mendelssohn is given little more than an anecdotal role in Foucault’s master narrative of Europe’s “impatience for liberty,” he nevertheless looms in Foucault’s essay as a reminder of a path not taken.3

Mendelssohn brings to the fore the intriguing role that Judaism assumed in the Enlightenment’s wider interrogation of religion. As Nathan Rotenstreich puts it: “it is a curious fact that the major systems of German philosophy were preoccupied to such an extent with Judaism.” For Rotenstreich, the reasons for this “curious fact” are mainly historical.4 He comments on the coincidence of the historical emancipation of the Jews with the development of the most influential traditions of German thought. As Hannah Arendt observes: “The modern Jewish question dates from the Enlightenment; it was the Enlightenment—that is, the non-Jewish world—that posed it.”5 In France and Germany the philosophers’ abstract questioning of liberty of thought had its concrete concomitant in political debates about the admission of Jews into civil society.6 Granting citizenship to the Jews became a test case for the enlightened nation. In historical terms, Judaism was far from an academic preoccupation for the new philosophes.

The near coincidence of Kant’s and Mendelssohn’s essays in the Berlinische Monatschrift in 1784 was not the first time that these two philosophers’ works had come into competition. In fact, Mendelssohn’s precedence in this debate merely repeats the pattern of an earlier encounter at the start of the two philosophers’ respective careers. Over twenty years earlier, Mendelssohn had effectively launched his philosophical oeuvre with an essay, “On Evidence in the Metaphysical Sciences,” which had defeated Kant’s own essay in the competition for a prestigious prize from the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. In this work Mendelssohn had set out to prove that metaphysics and the natural sciences share a methodology: the exercise of reason. This classic statement of Enlightenment optimism followed the program of extending the Newtonian revolution from the natural to the human world. Mendelssohn was thus, from the very start, the embodiment of an Aufklärer. His work and life brought him into contact with every important figure of his age—indeed a list of his intellectual and personal interlocutors reads like a Who’s Who of Enlightenment thought: Locke, Hume, Leibniz, Voltaire, Rousseau, to say nothing of Lessing, Jacobi, Hamann, Herder, and Kant.7 The scope of his work was also impressive. In addition to his essays and books on metaphysics and epistemology he wrote extensively on political theory, theology, and aesthetics (it was Mendelssohn, for instance, who inspired Lessing to write his Laokoon).

And yet, it is perhaps Mendelssohn’s alternative identity as the “Jew of Berlin” that has been his more lasting legacy. Mendelssohn’s career, contacts, and works all speak to the universalism of the Enlightenment project. His writings on metaphysics, epistemology, and aesthetics are written in a shared language of eighteenth-century European thought.

And yet, it is his particularity rather than his embrace of universalism that has more often than not marked him out for note in our histories of thought. In both his age and our own it is what Willi Goetschel has termed (with reference to Spinoza) the “scandal of his Jewishness,” which has made of Mendelssohn a figure of ambivalent fascination.8 Many have seen in Mendelssohn’s work at times an implicit and at other times an explicit attempt to find a mediating role between the poles of Enlightenment and Judaism, reason and religion. The theoretical framework for this venture has been found in his most influential work Jerusalem, or on Religious Power and Judaism. At the level of practice, Mendelssohn also engaged directly in the campaign of Jewish civil emancipation advocating equal rights and citizenship within the Prussian state.

His project of reformation had consequences on both sides of the ghetto walls. Mendelssohn’s attempts to improve the social status of Jews was mirrored by a reformist attitude within the Jewish community that he also helped to cultivate.9 His translation of the Psalms and Pentateuch into German was part of this attempt at greater cultural integration although he never followed a straightforward assimilationist stance.10 Mendelssohn’s German Bible was actually written in Hebrew script. The ambivalence of Mendelssohn’s attitude to German-Jewish relations has no more eloquent an expression than his translation of the Torah. As Jonathan Sheehan puts it, Mendelssohn’s translation

was, in a complex and contradictory way, supposed to give largely Yiddish-speaking Jewish children a subtly rendered German text in order that they might have access to the Hebrew original. One cannot help sympathize with the rabbi who complained that such a work “induces the young to spend time reading Gentile books in order to become sufficiently familiar with refined German to be able to understand this translation.”11

As Sheehan concludes: “The task was incredibly complex. Mendelssohn sought, at one and the same time, to train the Jews in German culture, to produce a German-Jewish literary monument, and to persuade Germans that the wisdom of the ancient Hebrews lived on in meaningful poetic and philosophical terms.”12 Just as Franz Rosenzweig and Martin Buber’s translation of the Bible stands as a testament of German-Jewish ambivalence at the beginning of the twentieth century, so Moses Mendelssohn’s German Torah in Hebrew letters expresses the ambiguous position of the enlightened Jew at the close of the eighteenth century.13

His role in this religious Enlightenment led Heinrich Heine to give Mendelssohn the title of the “Jewish Luther.” But within Judaism, Mendelssohn has always been more important as a symbolic figure of cultural fusion than as a radical doctrinal innovator. Conversely within Enlightenment philosophy, Mendelssohn represents the acceptable face of Judaism in a largely anti-Judaic tradition. It is as an honorable exception to his race that he is admitted into the mainstream of Berlin intellectualism. Immortalized by Lessing in his Nathan, der Weise, Mendelssohn represents the Jew who rises above the limitations of his people to achieve the status of universal humanity: the Jew, in short, who is no Jew. And yet, it is easy to overstate the tokenism of Mendelssohn’s role in the Aufklärung. He achieved a remarkable degree of integration and, far from being marginal, Mendelssohn was central to German thought in the second half of the eighteenth century. To his contemporaries he was not only an exceptional Jew but an exceptional thinker, one who was able to vie with Kant, after all, in the intellectual contests of his day. Mendelssohn was not only just a Jewish Luther or a wise Nathan, he was a “German Socrates.”

In this chapter I want to take this term, “German Socrates,” seriously as an incitement to investigate this fusion of Enlightenment thought and Judaism in a period of explosive German philhellenism. Through his identification with Socrates, Mendelssohn would attempt to secure for Judaism the same recognition that was accorded to Greco-Roman antiquity in this period. By claiming that ancient Jerusalem could act as a rival to the idealized societies of Athens and Rome, he insisted that its inclusions must have certain effects both for Judaism and for Enlightenment.14 Mendelssohn’s move was bold—it challenged the monopoly of Christian Enlightenment thinkers over the classical past. Mendelssohn would not only disrupt the binary of Greece and Rome, he would also render these classical models in Jewish rather than Christian terms.

Early in his career Mendelssohn set about writing a version of Plato’s Phaedo. Mendelssohn’s own dialogue on the immortality of the soul was an immediate bestseller; its first edition sold out within four months. It was subsequently published in numerous editions and translated into Dutch, French, Russian, Danish, Italian, and English all within Mendelssohn’s life time. His choice of dialogue is telling. The image of the steadfast Socrates calmly debating his own death with his anxious followers stages a classic scene of the triumph of reason over fear and superstition. But the choice of a dialogue on the immortality of the soul has a specific resonance within the religious discourse of the eighteenth century. The belief in immortality was, in Alexander Altmann’s words, “one of the few dogmas of natural religion.”15 Mendelssohn’s task in his Phaedon was to provide a proof of the immortality of the soul without reference to revelation. By putting his proofs in the mouth of the pagan Socrates, Mendelssohn attempts to show how immortality can be deduced from reason alone. Mendelssohn’s dialogue thus steers a course between the poles of Plato and Neoplatonism, between pagan reason and Christian revelation. His Phaedo represents an attempt to reclaim Plato for the Enlightenment. Mendelssohn wrests his Socrates away from the mysticism of the Neoplatonists and reinstalls him in the pantheon, so to speak, of rationality.

And yet, Socrates remained a problematic figure for the philosophes.16 For his eighteenth-century readers Plato bridged the gap between philosophy and theology. Through the Neoplatonist tradition, Socrates had come to embody not so much the opposition as the compromise between reason and revelation. If Christianity could appropriate Socrates as a precursor to Christ, Judaism tended to adopt an alternative chronology. Since Philo of Alexandria in the first century BCE, Plato had been identified as a follower of Moses. As Numenius is supposed to have put it “What is Plato but Moses speaking Attic Greek?” Divine truth, according to Philo of Alexandria, could be traced in an unbroken chain from Plato through Pythagoras back to Moses. Platonic doctrine, in this interpretation, was merely an elaboration of Old Testament wisdom. If Mendelssohn had so wished, it would have been easy for him to assimilate his Socrates to this theologizing tradition of Platonism. But there was more to this choice, for to choose to discuss the issue of immortality had a particular resonance in a German-Jewish context. Christians had long been critical of Judaism’s neglect of the issue of the immortality of the soul. The Hebrew Bible, they observed, had nothing explicit to say on the issue. From the Christian perspective, the question of immortality was just one more indication of the essential lack of Judaism. Whether we see this as a lack or a virtue, immortality is a Greek—not a Jewish—idea. Paradoxically Philo had to recourse to Plato to fill in the gaps of Jewish theology. Platonism is not so much the antithesis as the supplement to Judaism. Plato hardly represented the dangerous lure of paganism. Jews needed Plato to become better Jews.

Socrates, then, is an ambivalent figure of reason. When Mendelssohn chose Socrates and when his contemporaries for their part chose to identify Mendelssohn with Socrates, there was more at stake than any simple conflict between Enlightenment and religion. The epithet “German Socrates” expressed or, better, covered over a complex series of questions and anxieties about Judaism and its relationship both to pagan Athens and Christian Berlin. The reception of Plato in the late eighteenth century calls into question the Enlightenment’s embrace of a monolithic conception of reason. Moreover, the specific fusion of Platonism and Judaism in Mendelssohn’s work announces a new chapter in the long history of Socrates’ relationship to Moses.

The uneasy compromise between reason and revelation that preoccupies Mendelssohn in his Phaedon is also at the heart of his most famous work, Jerusalem. It is here that Mendelssohn explicitly defends Judaism against Christianity and sets out a vision of the ideal relationship between politics and theology. Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem, according to Altmann, represents “the first attempt at a philosophy of Judaism in the modern period.”17 Jerusalem, in fact, tries to pull off the ultimate sophistic challenge: to show that Judaism was not only reconcilable to the Enlightenment but also provided its most compelling model of a life governed by reason. His argument is bolstered by a historical interpretation of the political organization of the ancient Jewish polity. Flying in the face of the accepted wisdom of his age, Mendelssohn posits monarchic Jerusalem rather than democratic Athens or republican Rome as his paradigm of the enlightened city.

But despite his unorthodox contribution to the debate about antiquity, Mendelssohn proclaimed skepticism about the rise of historicism as the dominant mode of argumentation among his peers.18 Mendelssohn’s analysis of Judaism came under sustained attack in the nineteenth century by his more historically minded readers. For Mendelssohn had maintained the autonomy of reason from the vagaries of historical development and was particularly hostile to the master theories of historical progress that were so important to Lessing, Kant, and later to Hegel. As Matt Erlin has put it, “Mendelssohn . . . not only rejects the idea of global human progress; he also refuses to acknowledge any substantive distinction between past and present and thus seems to deny the very possibility of a modern age understood in terms of qualitative historical difference.”19 Mendelssohn’s complex use of history in Jerusalem has both an important philosophical role to play in the development of his own ideas about universalism and a wider resonance in the debates about the ruptures and continuities between antiquity and modernity in the eighteenth century.

Socrates and the Age of Enlightenment

If the twentieth century, in the wake of Freud’s compelling reading of Sophocles, has been known as the “age of Oedipus,” the eighteenth century could be called the age of Socrates. As Benno Böhm asserts, “Socrates is the ‘hell fire,’ which Eighteenth-century Man has to walk through” to come to a better understanding of himself.20 Socrates’ life and death have, of course, been a preoccupation for philosophers since the fifth century BCE. The eighteenth century, however, remains a distinctive moment in the transformation of Socrates into a figure of moder...