![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Traveling

In the late summer of 1839, the twenty-two-year-old Joseph Hooker was walking through London, accompanied by Robert McCormick, nearly forty years old and an experienced British naval surgeon who had already been on several voyages. The two men were preparing for a long ocean voyage, and as they crossed Trafalgar Square, McCormick recognized an old shipmate, a man Hooker later recalled as tall and “rather broad-shouldered,” with “an agreeable and animated expression when talking, beetle brows, and a hollow but mellow voice.” As Hooker remembered, when they stopped to chat, the newcomer’s “greeting of his old acquaintance was sailor-like—that is, delightfully frank and cordial.”1

The frank and cordial man was Charles Darwin, and this chance encounter marked the start of one of the nineteenth century’s most important scientific friendships, a friendship initially founded on the shared experience of traveling. Darwin could not have known that he was already one of Hooker’s scientific heroes; although his Journal of Researches (the Voyage of the Beagle) was still unpublished, a family friend had managed to get Hooker a set of printer’s proofs, knowing how much he enjoyed travelers’ tales. While he was waiting to set sail on his own voyage, Hooker slept with Darwin’s words under his pillow so that he could read them before he got up. Many years later he remembered that they had “impressed me profoundly, I might say despairingly, with the variety of acquirements, mental and physical, required in a naturalist who should follow in Darwin’s footsteps.” Nevertheless, that was what Hooker hoped to do and he was inspired by Darwin’s book, which stimulated his enthusiasm “to travel and observe.”2

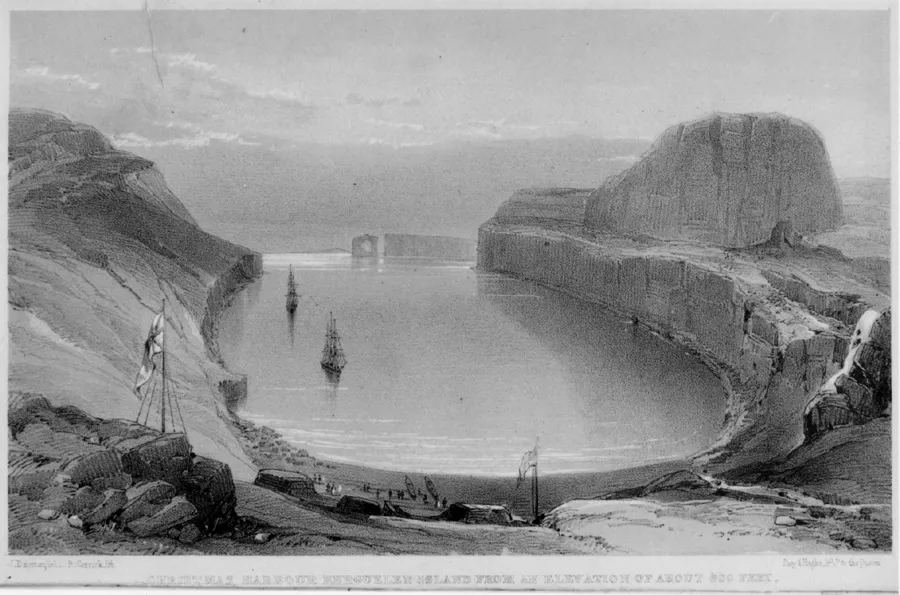

In the informal world of early-nineteenth-century science, with few university degrees and even fewer paid positions available, Darwin had chosen traveling as the best way to make a reputation for himself. His inspiration had been the renowned German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, whose narrative of travels in South America inspired many young men to undertake similar, hazardous scientific adventures.3 Among them was Hooker, whose first voyage, like Darwin’s aboard the Beagle, was a British naval expedition mainly concerned with mapmaking. When Hooker and Darwin first met, Hooker had just been appointed to a post aboard HMS Erebus, which, accompanied by its sister ship, the Terror, was about to set sail for Antarctica as Britain’s contribution to international efforts to map terrestrial magnetism (fig. 1.1). The expedition, which became known as the Magnetic Crusade, had been launched after a successful lobby of government by the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) and the Royal Society.4 Some leading British men of science were concerned that their nation’s scientific efforts were falling behind those of their European rivals and saw the expedition as an opportunity to reverse this decline. With this goal in mind, Humboldt himself had been persuaded to support the campaign, and the Royal Society had arranged for his letter urging the importance of the expedition to be printed and circulated among influential government figures.5 To be even a minor figure in such a high-profile expedition was, Hooker realized, an excellent opportunity. As he later told Darwin, “from my earliest childhood I nourished & cherished the desire to make a creditable Journey in a new country, & with such a respectable account of its natural features, as should give me a niche amongst the scientific explorers of the globe.”6

1.1 In the wake of Cook: HMS Erebus and her sister ship, HMS Terror, anchored in Christmas Harbour, Kerguelen’s Land. From J. C. Ross, A voyage of discovery and research in the southern and Antarctic regions, 1847. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

However, while Darwin and Hooker had similar goals, they traveled in very different styles: Darwin went as a gentleman companion to the Beagle’s captain, Robert FitzRoy, while Hooker was an assistant surgeon, subject to regular naval discipline. Darwin’s father’s wealth had allowed his son to spend long periods ashore, accompanied by his personal servant; by contrast, Hooker would have to fit his botanizing into whatever spare moments his medical and other duties permitted.

James Clark Ross, commander of the Magnetic Crusade, had met Hooker before they set sail. When Hooker made it clear that he hoped to become the expedition’s official naturalist, Ross had told him that he was looking for someone “perfectly well acquainted with every branch of Nat. Hist., [who] must be well known in the world beforehand, such a person as Mr. Darwin.” Ross had therefore decided to appoint the more experienced McCormick as naturalist. On receiving this unwelcome news, Hooker wrote to his father, complaining “what was Mr. D. before he went out? he, I daresay, knew his subject better than I now do, but did the world know him? the voyage with FitzRoy was the making of him (as I hoped this exped. would me).”7

Hooker confessed that he “must have looked very sorry and angry, which however [Ross] did not see, as he went on, speaking as kindly and almost as affectionately as ever, offering to write me letters of introduction to the surgeon and chief officers of the ship at Chatham, charging them to give me every opportunity of going ashore.” Despite this magnanimity, Hooker immediately did the rounds of his father’s influential friends, whose support had secured his place on the Erebus, asking their advice. He told his father that these advisers had “strongly disadvised my going except as the only Naturalist in the ship, the more especially as Dr. McCormick was to be my superior.” This seniority would give McCormick first claim on all the collections made during the voyage; as Hooker wrote, “all my notes on Molluscs and sea animals will naturally revert, from the Admiralty, to the Zoologist, besides which he will have more time on shore than I can.”8 Without access to these collections, Hooker would have little chance of publishing a broad work on natural history to compare with Darwin’s Journal.

Despite his disappointment, Hooker realized that the expedition was the best opportunity he had to make a name for himself; as he wrote, “No future Botanist will probably ever visit the countries whither I am going, and that is a great attraction.”9 After some further negotiations, he was able to tell his father “I am appointed from the Admiralty as Asst. Surgeon to the Erebus, and Capt. Ross considers me the Botanist to the Expedition and promises me every opportunity of collecting that he can grant.”10 Given that McCormick’s expertise was primarily zoological, Hooker seems to have realized that he would be able to take charge of the botanical collections, publish floras of the countries the ships visited, and thus establish a scientific reputation. But even if this ambitious plan failed, Hooker realized that accepting the post would mean that “I can always fall back on the service [i.e., the Navy] as a livelihood.”11

A few months later, on 30 September 1839, the Erebus and Terror set sail from England. It would be four years before they returned. Life aboard ship was uncomfortable and often dangerous (the ships came close to being wrecked on more than one occasion), and Hooker was often lonely. Yet, the voyage was indeed to be the making of him; he began his adult life as an underpaid naval surgeon but—thanks in large part to his travels—ended up as Sir Joseph Hooker, GCSI, KCSI, OM, president of the Royal Society, director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, and loaded with honorary degrees and medals from the world’s scientific societies.

However, while Hooker’s career illustrates some of the ways in which traveling provided the basis for a scientific career, his eventual success was also the product of botany’s rise up the scientific hierarchy of the day. From a peripheral aspect of medical training, botany would eventually become one of the great imperial sciences, playing a key part in exploring, cataloging, and exploiting the natural wealth of the empire. Hooker was to play a central role in the transformation of botany’s status—raising his science as he raised himself.

From Glasgow to Newcastle

In 1838, a year before the Ross expedition set sail, Hooker had attended his first meeting of the BAAS, in Newcastle; this was a crucial event for him, since this was where the lobby for the Magnetic Crusade was launched. These meetings brought together a rich diversity of practitioners of all the sciences from every class and background. In addition to the celebrated scientific dignitaries and their aristocratic patrons, the meetings were attended by self-improving mechanics, part-time meteorologists, astronomical enthusiasts, and artisan naturalists. The Westminster Review said of the latter group that “there are literally hundreds of such men scattered over the land—and they are a blessing to it” and went on to describe the sight of the “worthies of this class” attending “almost every meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science,” where they could “be seen enjoying the happiest day of their lives, by listening to dry and seemingly abstruse discourses in the Natural History section.”12

Part of the attraction for working-class “worthies” and other scientific newcomers was that the BAAS provided a rare opportunity for newcomers to catch a glimpse of the elite of British science. Hooker wrote to his grandfather Dawson Turner to describe a local bookshop that was “a sort of rendezvous for all the Newcastle strangers,” where he had spent some of his mornings because he “was sure of seeing 8 or 10 of the gentlemen, on one forenoon in particular, while reading there, I saw Buckland, Lyell, Sedgwick, Herschell [sic], Richard Taylor, Hutton, & several others.”13 Yet, despite his excitement at meeting some of the association’s celebrities, Hooker felt that, “with regard to the scientific department of the Association, it fell far behind the amusement & eating.”14 As he would soon realize, in the informal, sociable world of Victorian science, opportunities for amusement and eating, the chance to meet and make friends, were at least as important as formal meetings.

The astronomer John Herschel, whom Hooker glimpsed at Newcastle, had just returned from five years of significant astronomical work at the Cape Colony and was fêted by the BAAS. He was one of those who were convinced that British science was in decline, and he used his new celebrity to become a leading member of the “magnetic lobby,” joining the effort to convince the government to finance the Antarctic expedition.15 A couple of years later, while the Ross expedition was at sea, Herschel explained the importance of the magnetic survey to George Grey, then governor of South Australia. Herschel wrote that a full survey “of all the colonized and colonisable parts of Australia” and Britain’s other colonies was becoming vital, because “Surveyors are too apt to work by compass . . . making undue and erroneous allowances for the Magnetic declination, or deviation of the needle from the true meridian.” He claimed that most surveyors were unaware that the compass needle needed to be corrected in the light of local variations in the earth’s magnetic field and that “it is hardly possible to over estimate the amount of confusion and litigation which must be caused to the next generation when land becomes more valuable” if the surveys on which land tenure was based were not done accurately. Measuring magnetism was at least as important to the carving up of new colonies as it was to fully understanding the nature of the terrestrial globe. Herschel went on to inform Grey that magnetic surveys were already under way in Canada and at the Cape, and that the governments of the Australian colonies had an ideal opportunity to make their own, since “a magnetic observatory now exists in full activity in Van Diemen’s Land” which could provide “a centre of reference . . . upon which any extent of operation might be securely based.”16 That observatory had been set up by Ross’s expedition (fig. 8.3) and Hooker had been present at its inauguration, so the economic value of the imperial scientific enterprise of which he was part would have been obvious to Hooker from the earliest stages of his career.

Meanwhile, the Newcastle meeting gave Hooker early news of the impending Antarctic expedition—which gave him a chance to fulfil his ambition of joining the scientific elite he saw around him—but it also offered a rather sharp reminder that his science, botany, was not held in anything like the same esteem as Herschel’s astronomy. Whether one examines the money the BAAS disbursed, its published reports, or the comments of its leading lights, it is clear that during the 1830s and 1840s natural history was not highly regarded and that botany sat even lower than zoology. These attitudes directly affected Hooker’s career prospects, because the association’s implicit disciplinary hierarchy was closely linked to the funding it provided (and it was the largest source of scientific funding in Britain at the time). 17

At Newcastle, Hooker was struck by the lack of attention paid to botany and natural history. He observed that “the sections were very variously attended, the Geological was always the most crowded, then the Mechanical & Physical, the Medical was farthest behind of any”—which not only confirmed its lowly status but tainted botan...