The Establishment of Hysteria as a Medical Category

In 1818, Jean-Baptiste Louyer-Villermay dedicated nearly fifty pages to hysteria in Charles-Joseph Panckoucke’s Dictionnaire des sciences médicales (Dictionary of Medical Sciences), thereby establishing its importance as a medical category.2 The text begins with a list of twelve diagnoses, which are presented as so many synonyms: “hystéricie, hystericism, hysteralgie, hysteric passion and hysteric affection, uterine affections, suffocation of the womb, strangulation of the uterus, fits of the mother: this illness has also been called ‘hysteric vapors,’ ‘ascension of the womb,’ and ‘uterine neuroses.’”3 Louyer-Villermay was attempting to present the category of hysteria as encompassing maladies that had existed for centuries but that could now be approached ahistorically. His contribution was not so much a recognition of specific symptoms as a gathering together of divergent and conflicting interpretations. Louyer-Villermay’s act of definition served as an opportunity to eliminate certain features of hysteria and force through others, with the aim of facilitating the physician’s use of the diagnosis. Through a series of equivalences, he reduced a broad spectrum of approaches to the body to a unique pathology.

After placing these theories under the aegis of a single category, Louyer-Villermay proceeded to assign them a single point of origin: the female uterus. He justified his selection of the term “hysteria” as follows: “It expresses the idea attached to it quite well, and . . . use has consecrated it.”4 The noun was read as metonym, functioning as proof that the origin of the illness was in the womb. Louyer-Villermay continued:

Were it not so, one would at least have to change the denomination; for the word “hysteria” implies the nonexistence of this illness in the man. The impropriety of terms being, in science, the first twist given to reason, this word could not have been kept if it did not represent an exact idea, that of an illness proper to woman.5

The choice of the word “hysteria” was thus confirmed in the name of upholding the validity of contemporary science, along with an explicit concern for the exacting use of terminology. An equivalence was postulated: a perfect reciprocity between idea and terminology would lead the way toward a complete and exact grasp of the pathology. In 1816, Louyer-Villermay summarized in a single sentence the transformation of the suffocation of the womb, the vapors, and various hysteric illnesses into what would come to be seen as hysteria: “A man cannot be hysterical, he has no uterus.”6 He presented this assertion as evidence that was firmly grounded in centuries of medical history. The creation and use of the category hysteria had thus become an accomplished fact, and the lack of any direct opposition to the use of the term allowed Louyer-Villermay to claim a consensus—even making this consensus the crux of his explanation. Still, in 1818 it was a recent and fragile consensus, and occurrences of the term “hysteria” had been rare until its appearance in Panckoucke’s dictionary.

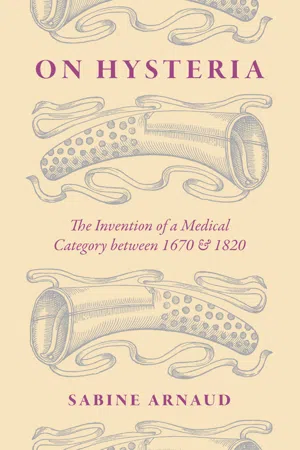

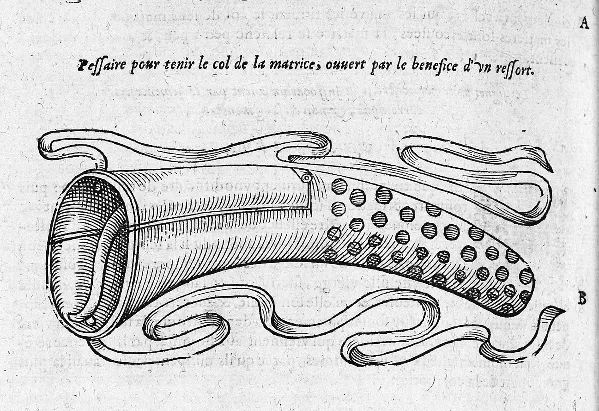

As it happens, it was the use of the term by two eminent physicians during the first two decades of the nineteenth century that allowed Louyer-Villermay to assert the category in such an authoritative manner. The physicians represented rival institutions: Joseph-Marie-Joachim Vigarous was professor at the Faculty of Medicine in Montpellier, while Philippe Pinel held the equivalent post in Paris.7 In 1801, Vigarous assimilated seven diagnoses under the banner of hysteria in his Cours élémentaire de maladies des femmes (Elementary Course on the Illnesses of Women).8 Meanwhile Pinel defined hysteria as a kind of neurosis in his nosographical works. Pinel, the chief physician at the Salpétrière, did not merely localize the origin of the pathology in the female organ; he further identified the dysfunction of the body as resulting from unassuaged sexual needs. To confirm the origins of the pathology, he referred to an ancient medical practice: “The primitive seat of hysteria, as its name indicates, is the womb, and very often too an austere continence is one of its determining causes; this has given rise to a method known to all matrons, and which Ambroise Paré describes with his usual naïveté, prescribing then the use of frictions.”9 Citing a therapeutic practice in this manner gave Pinel an expedient means to establish the origin of the pathology.10 On the one hand, Pinel attempted to remove all doubts by appealing to the authority of Ambroise Paré, Henri II’s adviser and surgeon, famous for having revolutionized surgery. On the other, the reference to Paré allowed Pinel to present himself and medicine from a relatively decorous perspective, separating the more abstract world of physicians from that of surgeons and midwives. The “method known to all matrons” was the use of masturbation and the insertion of a pessary into the vagina (fig. 1). This instrument was a perforated metallic cylinder through which the fumes of various herbs would pass (fig. 2). These fumes were meant to attract the womb toward the lower part of the belly, thereby combating the suffocation of the womb thought to result from its ascension. By using the crude authenticity of Paré’s words as additional proof of his assertion, Pinel was able to present hysteria as an exclusively female affliction, with its origin localized in the uterus.

For Pinel, Vigarous, and Louyer-Villermay, the very name “hysteria” operated as proof of the origin of the pathology, which was now attached to a specific gender. Further, for lack of a better argument, the etymology of “hysteria” made it possible to explain the causes of its symptoms. A strict equivalence was established between the noun, the idea, and the origin of the pathology, exhibiting a theoretician’s desire for methodological rigor. Here again, the etymological root was used as a means to ennoble science, and the category of hysteria was in part validated through an appeal to the authority of classical antiquity.

When justifying their terminology, Louyer-Villermay and Pinel did not mention that “hysteria” was a relatively new term, one that was absent from the treatises they themselves considered most relevant.11 Admittedly, the evocation of a hysteric pathology with an origin in the womb went back to ancient times. Ilza Veith identifies a first description in the Kahun Papyrus (1900 BC), though she adds that no equivalent of the term “hysteria” itself can be found in any of these texts.12 When examining the long genealogy of “hysteria,” it is easy to neglect the fact that in French and English the adjective “hysteric” does not appear until the second half of the sixteenth century.13 King Lear’s mention of hysterica passio14 was one of its first appearances in the literary space,15 but the noun does not appear in French until 1703 or in English until 1764.16

As Étienne Trillat and Helen King have shown, in the Hippocratic corpus the treatise On the Illnesses of Women expounded on illnesses “of the uterus” or those “localized in the uterus.”17 One of these illnesses, referred to as suffocatio hysterica, was characterized by convulsions, breathlessness, and suffocation. An aphorism from the Hippocratic corpus proposed marriage as its most appropriate treatment. Because the description was so vague, authors would be able to cite these texts for centuries to come. Until the twentieth century, for example, the necessity for marriage would continually appear as a polite means of speaking about the womb’s inopportune desires. An ancient aphorism, the similarity of a few symptoms—these were the seeds of a lengthy tradition, the origin of a palimpsest, a series of references repeatedly rewritten and erased, constituting a sedimentation of references for thinking about hysteria. Cross-references to hysteric illnesses would give shape to future medical treatises despite the absence of the term itself. By reading hysteric affection as Hippocrates’s discovery, physicians of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries became invested in a highly specific genealogy of texts.

What happened, then, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, for the etymology of the word to make the cause of this pathology a statement of the obvious? What specific symptoms were implied by the diagnoses that Louyer-Villermay compiled in Panckoucke’s dictionary? And was the uterus singled out as the origin of these symptoms? How did hysteria become a “women’s illness”? Around 1800, interest in hysteria fell within a movement to reorganize medicine into a unified and closed body of knowledge. Traditions at times parallel, at times opposed, were associated with each other through echoes and quotations that were repeated or at times transformed. Vigarous, Pinel, and Louyer-Villermay conceived of their work as an attempt to achieve convergence, a retrospective attempt to recognize and clearly identify that which had previously been known only indistinctly. Charles E. Rosenberg has argued that “in some ways disease does not exist until we have agreed that it does, by perceiving, naming and responding to it,”18 and the reinscription of symptoms and diagnoses in new categories also results in a repeated refashioning of diseases. Looking back to the late sixteenth century and following the terms and interpretations attached to each of these illnesses will demonstrate just how shifting and variable these interpretations had been. However, considering the use of the terminology rather than its origins also makes it possible to ask how a term prompted a way of thinking and erased the gap between naming an illness and situating its origin. The word is examined here in its capacity to anchor and transform an accompanying discourse, as a point of departure for a series of utterances within the field of knowledge. The use of the term produced an epistemological shift as different afflictions converged in the diagnosis “hysteria.” Between 1575 and 1820, perceptions of the pathology’s association with gender, with class, and with religion developed along different trajectories and through different forms of narrating, explaining, and citation. How were these categories used, on what occasions, and with what agendas? What kind of displacements and gaps appear in the use of terms that were later gathered into the category of “hysteria”?

An Intermingling of Terms

Until the end of the seventeenth century, writings on the suffocation of the womb,19 uterine suffocation,20 uterine furor,21 mal di matrice,22 melancholic furors,23 loving rage,24 erotic melancholia,25 and fits of the mother26 indicated a variety of symptoms, notably paleness, stifling, stiffness, swoons, and catalepsy. The theorizations and references contained in these texts closely followed a long tradition of Greek, Latin, and Arabic works, retraced by Helen King.27 The predominant category of the era was “suffocation of the womb,” for which the first description in vernacular appeared in the work De la Génération (On Generation) by Ambroise Paré, published in 1561.28 From then on, this type of diagnosis became a subject of medical inquiry in works addressing medical practitioners and devoted to women’s illnesses and generation.29 Despite the variety of names and contexts in which the description of such symptoms took place, most works indicated that hysteric illnesses were caused by vapors, which would eventually become a diagnostic term in its own right. Vapors circulating throughout the body became the explanation for pathologies exhibiting all manner of symptoms, attacking different parts of the body, without an immediately assignable cause or progression of symptoms. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, some physicians also described a “wandering womb” and ascribed the cause of suffocation to the womb’s movements.30

Jean Liébault, the sixteenth-century medical practitioner at the Faculté de Paris, wrote that vapors were a consequence of retaining menstrual blood.31 In his Trois Livres des maladies et infirmitez des femmes (Three Books on Women’s Maladies and Infirmities), published in 1598 and reprinted and expanded in 1651,32 Liébault situated the origin of the pathology in the lower belly. According to him, the womb could move upward and along the side of the woman’s body—even if the rare dissections of the time did not make it possible to identify where the womb would migrate or the vapors circulate.33 Such movements provoked contractions of the diaphragm, resulting in the womb’s suffocation as it sought to expel vapors and excess air. But in which directions did these vapors migrate? Liébault described the vapors as moving through veins, arteries, and occult openings inside the body.34

Similarly, André du Lauren...