![]()

1

Persons and Places, 1903–1922

The date and place of Countée Cullen’s birth cannot be known with complete certainty. Research into these questions, however, has turned up pieces of information that can be assembled into something like a broken mosaic. Briefly told, the poet was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1903, of a woman called Elizabeth Lucas and a man named John, or John Henry, Porter. Presumably because he was born out of wedlock, Cullen remained quite reticent about the details of his birth and early life. Sometime in the early years of the twentieth century, however, the boy apparently was brought to New York City, where he would spend the major portion of his remaining years. In the 1910 census for New York City, the official record shows a family named Porter—this was the name Cullen went by for the first fifteen years or so of his life—living in Manhattan, and this particular family’s head was listed as Henry Porter.1 The female in the household was called Amanda, and there was one child living with them, named “County,” the phonetic version of the name the census taker must have heard. The census taker also assumed that Amanda was Henry Porter’s wife. However, later evidence establishes that Amanda Porter was in fact Cullen’s grandmother, not his mother. All three were listed as black, and all were born in Kentucky. Many years after the census was taken, Cullen confirmed to Harold Jackman, his closest friend, and to Ida Cullen, his second wife, that his birthplace was Louisville, Kentucky.2 The census listed the boy “County” as being eight years old, which would make his birth date 1902 or 1903—and when he was an adult Cullen himself consistently listed the latter date on various applications and official forms; he also repeatedly named New York as his place of birth. The census taker entered Mr. Porter’s occupation, cryptically, as “Theatre,” and years later faint rumors mentioned his work as a doorman or porter at one of New York’s many flourishing theaters. So, on this evidence, the poet’s date and place of birth can be fairly well established, though no document, such as a birth or baptismal certificate, validates the story further.

Beyond these frail facts, however, little can be discovered about Cullen’s first five or six years. Probably the family was poor, maybe even desperately so. The Porter family did seem to change their New York residences often. Records of the young boy’s earliest schooling, all of which was conducted in the New York Public School System, complete the picture of transience. Inquiries sent to the board of education in New York back in 1960, and answered by Claire Baldwin, an assistant superintendent, record his earliest years as a student.3 He attended several grammar schools: he went to the first grade at P.S. 27 in Manhattan, in February 1908, and stayed at that school until June 1911. Then he was enrolled for a year each at P.S. 43 and P.S. 1 (the latter in the Bronx), followed by two years, also in the Bronx, at P.S. 27, from which he graduated.4 Only speculation could answer why he, and presumably his parents or grandparents, moved around so often. Assistant Superintendent Baldwin, however, supplied a clarifying address for the period when he was enrolled in P.S. 27 in Manhattan: 668 Third Avenue. This is the same address listed on the 1910 census. The documentary record slowly becomes clearer. His grammar schooling culminated in his admission to Townsend Harris Hall, a preparatory high school run by the City College of New York, where the grades on his exams were commendably high. His registration form from there lists several more pieces of information. His father’s name is given as John Henry Porter; he was sent to the School of Commerce in January 1917; his residence is listed at 190 West 134th Street, as the family settled in Harlem; and his date of birth is given as May 30, 1901 (though the final two digits are hard to read.) Some accounts had mentioned that Cullen attended Townsend Harris for one year, though none mentioned the marginal note on his transcript, namely, that he was transferred to the School of Commerce for a short period prior to his going to DeWitt Clinton. Thus, slowly and piecemeal, some of the early facts about Cullen’s life are established.

What is tentatively drawn out from this picture, however, in certain ways conveys less than the settled fact that Cullen himself chose not to record many of these details. After he became a well-known poet and cultural figure, he might readily have recorded his biographical information on the various applications he completed and in numerous interviews he gave to newspapers. But he chose not to, and for reasons he kept equally to himself. For several decades after his death, people recounted or speculated on what was mainly a missing record: his birthplace was listed at different times as New Orleans, Louisville, Baltimore, or New York City. Even his birth date was never definitively established, for while May 30 was cited, the year varied from 1900 to 1903. An undated issue of a short-lived Harlem newspaper of limited circulation and reputation, called Headlines and Pictures, adds some details.5 It tells of Cullen’s mother (more likely his grandmother) being obese, so much so that she was often embarrassed to leave her house. She supported herself by taking in foster children, presumably after her husband passed away. All in all, there were possibly features of Cullen’s childhood, not least the frequent changes of residence, which could fairly be called Dickensian.

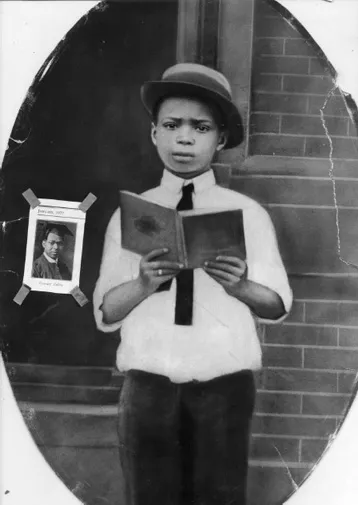

Among the large number of records, letters, and documents that Cullen kept throughout his life, a unique item stands out. This is an oval portrait, either a photograph or done with considerable skill in pencil and measuring twenty inches high and fourteen inches wide. The subject, a young boy, is clearly Countée Cullen. Staring straight out at the camera, his face conveys a mixture of innocence and self-possession. Ida Cullen, in her reminiscences, says that the portrait is of Cullen, and that he brought it with him when he returned from Kentucky, where he had gone to attend his mother’s funeral.6 Adding to the portrait’s importance, a small reproduced photograph, about one-and-a-quarter inch square, has been taped to the lower left part of the oval. This depicts Cullen’s graduation from college, as he is shown wearing the traditional cap and gown. It seems quite likely that Elizabeth Lucas was somehow given the oval portrait and kept it with her in Louisville. She very probably clipped the small graduation portrait of her son and taped it to the larger picture (see figure 1). When Cullen brought the picture back to New York after his mother’s funeral, it was one of the rare times when he retrieved and kept a physical memento of his childhood.

1. A photo of Cullen as a young boy, which has his Harvard graduation photograph (dated January 1927) attached to it. Cullen brought it back with him to New York from Louisville, where he attended his mother’s funeral.

Elizabeth Lucas died on October 25, 1940, aged fifty-five, and was buried in Louisville. A close friend and neighbor, Mrs. Martha Fruits, notified Cullen, who asked her to arrange everything according to his wishes, namely, that she be buried from her home, without any church ceremony. The funeral director, Mr. R. G. May, sent Cullen a bill for $218 to cover the funeral services, which Cullen paid in cash.7 (This also indicates that he went to Louisville for the burial.) Written in either Cullen’s or Ida’s hand is a note on the back of the envelope that contained the bill: “Important Mother’s funeral bill.” Later research would lead to interviews with people living near Elizabeth Lucas, and they confirmed that she had had a son, that “he worked as a teacher in New York and that he was writing books,” and that he sent her a monthly check.8 (Since the mailing address for Elizabeth Lucas is written in Cullen’s small phone directory that he carried in the 1930s, this last point gains further credibility.)9 The people in Louisville remembered Cullen’s arrival and his gentle and diligent efforts to arrange the details of the funeral, which was delayed until he could reach the city by train. He expressed his thanks to all of those who assisted him throughout what was obviously a moving experience.

There are two more documents, however, that tell a great deal: death certificates that are likely his grandfather’s and his grandmother’s.10 On January 22, 1917, at the age of fifty-two, John H. Porter died in New York City of “acute lobar pneumonia.”11 According to the certificate, he had lived in the city for fourteen years—arriving just around the time of Cullen’s birth. What strongly indicates he was Cullen’s grandfather is that his address is given as 190 West 134th Street. (The character of the premises is shown as “tenement.”) Nearly a full year later, at Manhattan Harlem Hospital, on December 8, 1917, Amanda Porter passed away. Her address is likewise listed as 190 West 134th Street, the same as that given on John Porter’s death certificate and on Cullen’s Townsend Harris Hall registration form.12 The certificate also says that she was forty-eight years old and had lived in New York City for eighteen years. This means she came to the city, from Louisville most likely, at the age of thirty, in 1900. Perhaps she preceded Henry Porter to New York and was later called on to help raise her grandson.13 It is perhaps the case that Countée’s father remained in Kentucky, but then, without wedding Elizabeth Lucas, decided to send his son to the city where Amanda had taken up residence. But things are far from certain.

It was, in any case, first in late 1917, and then for the nearly thirty years following, that Cullen—now an orphan—resided with the Reverend Frederick Ashby Cullen, the pastor of the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the largest in all of Harlem. From then on, his life records become clearer and clearer, though his early childhood remains largely visible only in outline form.

Because Cullen never corrected the uncertainty about when and where he was born, it makes the reconstruction of his first years difficult, but not impossible. The absence for many years of such a reconstruction has nevertheless influenced, if only to some extent, the critical reception of Cullen’s poetry. Among critics and scholars the sense began to dominate quite early that he was withdrawn and secretive. Added to the questions of his place and date of birth, there is the problem of a comparative lack of diaries or autobiographical accounts or essays that could help create a more finely etched portrait for the early years. In similar cases where life details are missing, critics and scholars have turned to the works of the author—the obvious case is Shakespeare—to satisfy the reader’s appetite for more knowledge. Even here there is some frustration, for Cullen’s poetry is not ostensibly autobiographical. His earliest poems date from around his fifteenth year, but they don’t revisit or reminisce about his previous experiences or thoughts or dreams.

Looking ahead to a moment in 1925 when Cullen published a poem called “Fruit of the Flower,” he left a highly symbolic picture of his father and mother. Though it is impossible to tell if he speaks of his natural or his adoptive parents, what he says unveils a great deal about his attitude toward parentage and filial ties.

My father is a quiet man

With sober, steady ways;

For simile, a folded fan;

His nights are like his days.

My mother’s life is puritan,

No hint of cavalier,

A pool so calm you’re sure it can

Have little depth to fear.

The poem at first praises the parents’ solidity, but then goes on to picture both parents as perplexed by their child’s “wild sweet agony.” The drama in the poem could be read as a stereotypical verse about a young man’s rebellion, while nevertheless reasserting the true ties that bind parents and their offspring. The poem ends on a definite note, though in the form of a rhetorical question, which allows Cullen to strike a balance between rebellion and acceptance.

Who plants a seed begets a bud,

Extract of the same root;

Why marvel at the hectic blood

That flushed this wild fruit?

By picturing a child who at one and the same time rebels against his parents and insists that they should accept him—indeed, accept the responsibility they incurred by having him—the poet claims the energy of his autonomy even as he professes the stability of his birthright.

The first fourteen or so years of Cullen’s life, outside of his school records, remain largely a blank as far as any vivid eyewitness account goes. Of course, these years were not a blank to him. This means that, given the absence of his own testimony, he went to some considerable effort to conceal from everyone, and in part from himself, just what those years signified to him. The persistent air, not of secrecy exactly, but of an exaggerated reticence entered into many of the later psychological images of Cullen. This is not altogether unheard of in the case of lyric poets, who after all spend much of their literary effort revealing some of their deepest and most closely watched emotions, but only through the strict mediations of artistic form. One of the most obvious facts about Cullen is his race, and all the attendant emotions and values that come with it. What precise strategies he might have developed early on to deal with the affronts and wounds of racism can only be guessed at, though clearly he couldn’t proceed carelessly. His intelligence was manifest early, as was his love of musical words and a fascination with stories out of books. As with any memorable lyric poet, the song may be the truest account of the self, even as the life offers its own lights and shadows.

After the first fourteen years or so of his life, however they transpired, Cullen grew plainly and visibly planted in New York City, and more pointedly in the section called Harlem. His poetry, however, possesses few marks of urban life in its harshest aspects. Rather, he had the cosmopolitan’s sense of the city, a place where the art and culture of previous centers of civilization are profusely and variously available. Dressed constantly as an adult in his three-piece suits—just like W. E. B. DuBois and Alain Locke, mentors for Cullen and widely respected “race men”—he added the elite touch of his Phi Beta Kappa key and chain across his vest. New York appealed to whatever sense of the theatrical Cullen allowed himself, and there are stories of his great zest and talent on the dance floors of many Harlem parties.

Whatever the unknowable circumstances of his birth and early childhood, Cullen possessed certain traits that occasionally made him seem unhoused. Later in life he would travel summer after summer to Paris and parts of Europe. Paris became like a second home, and he praised its ways intensely. He also wrote children’s books, as if to circle back and supply himself with a source of comfort otherwise denied him in his first years. Rather late in life he retreated to Tuckahoe, New York, in Westchester County, north of New York City, to escape the wear and tear of Harlem and what had become the megalopolis, perhaps in answering a call to some early pastoral memories. Many of his poems, especially the early ones, speak of loss and departure. These supply standard subjects for lyric poetry, but Cullen may have known more of their lineaments than other people did. One of his most famous poems, “Incident,” recounts visiting a new city, confronting racial hatred, and having it erase all the positive thoughts that he might otherwise have enjoyed.

If his birth year is taken as 1903, this meant Cullen entered the world the same year W. E. B. DuBois published The Souls...